More than just a Cheeky Bum

Posted on: 16 October 2020 by Dr Amanda Draper, Curator of Art & Exhibitions in 2020

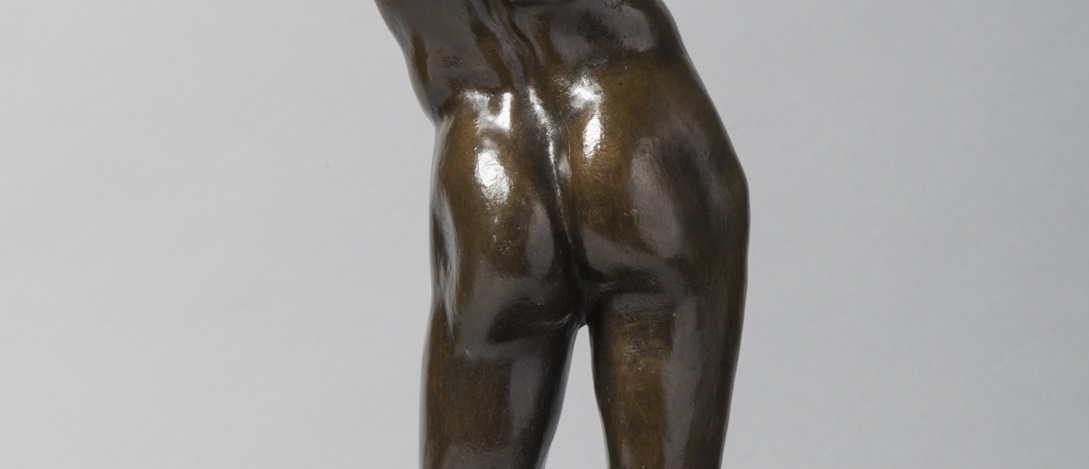

In recent weeks a particular part of one of our sculptures has been getting a lot of attention: its buttocks. They have featured in the Liverpool Echo and on various social media platforms including one called @museumbums (yes, really …). But there is more to ‘The Sluggard’ than its pert behind, so let’s get to the bottom of the story.

The Sluggard (back view)

Whose bottom is it?

When Frederic Leighton saw his model rise and stretch after a lengthy session posing for the artist, he was apparently inspired to create a sculpture based on the movement. In a biography of the artist published in 1906 called ‘Lord Leighton of Stretton’ by art historian Edgcumbe Staley, the model was named as Giuseppe Valona. So we know who ‘The Sluggard’ was – or do we?

Almost every subsequent reference to ‘The Sluggard’ gave the model’s name as Giuseppe Valona. But in 2001 a family came forward saying that they had found a hand-written 500,000 word biographical manuscript written by their great, great grandfather named Gaetano Valvona. He described how he was an artists’ model in London and how he inspired the famous sculpture ‘The Sluggard’. So Staley had misquoted the model’s name and the history of ‘The Sluggard’ had to be amended.

The Sluggard (detail)

Born in 1858 to a family of shepherds in the Naples area, Valvona probably met Leighton during the artist’s many travels around Italy and eventually returned to London with him to work as a professional artists’ model. He posed frequently for Leighton, but also for other important artists of the time including John Everett Millais, Hubert von Herkomer, Lawrence Alma-Tadema and Edward Poynter.

When he first arrived in London, Valvona wrote how he was still wearing his shepherd clothes, which led to local urchins throwing stones at him and chasing him through the streets of Clerkenwell where he lived. Leighton took pity on him and sent him shopping with a servant for less conspicuous outfits.

When he first arrived in London, Valvona wrote how he was still wearing his shepherd clothes, which led to local urchins throwing stones at him and chasing him through the streets of Clerkenwell where he lived. Leighton took pity on him and sent him shopping with a servant for less conspicuous outfits.

The Sluggard by Frederic Leighton, 1890 (bronze). 52.1cm high

Sir Frederic Leighton

Leighton could afford to be generous. He was the premier British artist of the later 1800s and was at the very pinnacle of success when he worked with Valvona. Leighton was born into a wealthy family. His grand-father had been a doctor, tending to the Russian Czarina in St Petersburg, and his father was also a doctor. Although he was born in Scarborough, his family spend much time abroad due to his mother’s ill-health, and most of his artistic training was undertaken on the Continent in Germany and Italy. He lived in Paris during his late twenties before moving back to London in 1860 and rapidly making his mark. Queen Victoria purchased the first painting he exhibited at the Royal Academy, the foremost art institution in Britain, and his reputation was made. He was elected an Associate of the Royal Academy in 1864, full Academician in 1868 (and knighted in the same year), and made President of the Royal Academy ten years later. Leighton continued as President for the rest of his life.

![Henry Jamyn Brooks: Private View of the Old Masters Exhibition at the Royal Academy, 1888. [oil on canvas] © National Portrait Gallery, London. Leighton is the central bearded figure in the brown coat.](https://vgm.liverpool.ac.uk/media/livacuk/victoriagalleryandmuseum/blog/Cheeky,Bum,Blog,4.jpg)

Henry Jamyn Brooks: Private View of the Old Masters Exhibition at the Royal Academy, 1888. [oil on canvas] © National Portrait Gallery, London. Leighton is the central bearded figure in the brown coat.

Leighton’s wealth and status in the art world was manifest in his magnificent London home on Holland Park Road in Kensington, which was also his studio. He purchased a plot of land there in 1864 and then engaged his friend, George Aitchison (1825 – 1910) to design the house. Although he was an architect, Aitchison specialised in industrial buildings like warehouses and Leighton’s was the first domestic house he had built. From the outside, the house was quite plain but subsequent additions to the basic building increased its opulence inside, culminating in its spectacular Arab Hall extension (1877 – 81) which used sumptuous marbles and antique Middle Eastern tiles. Its style was influenced by Leighton’s travels to Sicily, Turkey and Syria, with Leighton drawing on the expertise of fellow artists Walter Crane, ceramicist William de Morgan and sculptor Edgar Boehm. Leighton House is now a museum for all to enjoy.

Interior of Leighton House. Photo © and with permission of Leighton House Museum

Leighton the Painter

First and foremost, Leighton was a painter. He undertook some portraits to commission, but most of his output comprised grandiose scenes based around classical mythology, biblical stories or literary themes. These days examples of his work can be found in all the major art galleries in the U.K. and in private collections around the world. In fact, below is our friend Gaetano Valvona posing up a storm in Leighton’s ‘And the Sea Gave up the Dead Which Were in it’ from the Tate collection. The tondo shows a scene from the Book of Revelation (revelation 20:13) with the drowned awakening and rising up into fiery skies.

Frederic Leighton: And the Sea Gave Up the Dead Which Were in it, c.1892, (oil on canvas). Photo © Tate

Leighton the Sculptor

Remarkably, Leighton only produced three sculptures during his long career, but they had an enormous influence on the prevailing artworld. His first sculpture, made with assistance of established sculptor Thomas Brock, was a life-size figure with the descriptive title of ‘An Athlete Wrestling with a Python’. It was Leighton’s reaction against the rather pallid figurative sculpture of the day, and paid homage to ancient Greek sculpture with its dynamic form showing realistic twisting movements, defined musculature and expressive face. The spiralling composition of man and snake make the sculpture equally compelling from whichever angle it is viewed. The model for this work is believed to be another Italian, Angelo Colorossi, although it is sometime said to be Valvona.

An Athlete Wrestling with a Python by Frederic Leighton, 1877 (bronze) Photo ©Tate

The sculpture was first displayed at the Royal Academy exhibition of 1877 and created a sensation. It is widely considered to have inspired an entire movement in British art known as the New Sculpture, where mythological, allegorical and Symbolist themes were depicted using naturalistic poses in a decorative way.

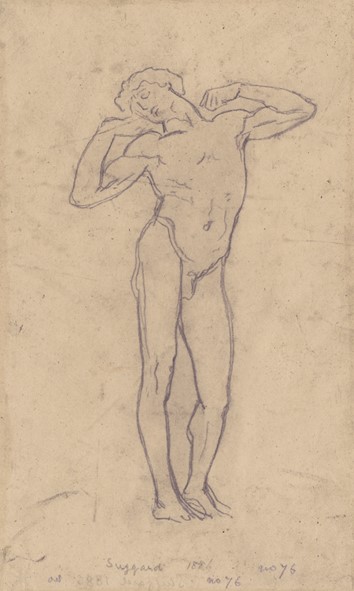

‘The Sluggard’ was the second of Leighton’s sculptures, again working with Thomas Brock, and again a life-size figure cast in bronze. As we know, it was reputedly inspired by Leighton seeing his model Valvona stretching after a session posing. According to Staley, ‘The Sluggard’ was originally called ‘An Athlete Awakening from Sleep’, and was supposed to be a counterpart to ‘An Athlete Wrestling with a Python’, but Leighton chose to rename it. The sculpture was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1886 to more plaudits. At the same exhibition, Leighton also showed his third and last sculpture: a bronze statuette about 50cm high of a young girl being startled by a toad called ‘Needless Alarms’; rather a contrast in subject-matter to his other two sculptures.

The Sluggard by Frederic Leighton, 1885 (bronze) Photo ©Tate (left) and (right) Needless Alarms by Frederic Leighton, 1886 (bronze) Photo ©Tate

It may have been the success and size of ‘Needless Alarms’ that gave the idea of creating a smaller scale version of ‘The Sluggard’ that could be sold in numbers. The reduced version at 52.1cm follows the same ‘contrapposto’ pose, with weight on one leg and twisted torso, which gives the form dynamism and interest, but there is less detailing. The fig-leaf is missing for one thing, plus the garland at the original’s feet.

Tracing for The Sluggard by Frederic Leighton, 1886 (pencil on tracing paper). © and permission of the Royal Academy of Arts

The task of producing the scaled-down statuettes of ‘The Sluggard’ was awarded to Arthur Leslie Collie of London, himself a sculptor, and they were cast by the foundry of J.W. Singer and Sons of Frome, Somerset. The first editions were issued on 1st May 1890 and the VG&M’s is one of these. Editions were published into the 20th century but with diminished quality.

![Frederic Leighton by Window & Grove, c.1880 (albumen cabinet card) ©National Portrait Gallery, London [note incorrect spelling of his first name]](https://vgm.liverpool.ac.uk/media/livacuk/victoriagalleryandmuseum/blog/Cheeky,Bum,Blog,11-340x553.jpg)

Frederic Leighton by Window & Grove, c.1880 (albumen cabinet card) ©National Portrait Gallery, London [note incorrect spelling of his first name]

Endings

Sir Frederic Leighton continued his illustrious career and was productive until the end, although he never created another sculpture. He was made a peer of the realm in 1896, to be Lord Leighton of Stretton, and was the first artist to be elevated to this rank. Unfortunately he died the day after so, sadly, also holds the record of having the shortest peerage on record.

Gaetano Valvona married and had eleven children with his wife Celester. He appears to have found work harder to come by as he got older and struggled with debt. He died in Hendon, Middlesex in July 1915 aged 58. However, he did merit an obituary in the Daily Chronicle which described him as the most popular model in the artists’ studios around Chelsea.

Our edition of ‘The Sluggard’ came into the collection in January 1989 and was purchased from a London dealer with support from the National Art Collections Fund (now called the Art Fund). It had previously been in a private collection in America.

More information sources:

Frederic Leighton and Leighton House

https://www.rbkc.gov.uk/subsites/museums/leightonhousemuseum1.aspxt

‘Tracing for The Sluggard’ at Royal Academy of Arts, London

https://www.royalacademy.org.uk/art-artists/work-of-art/tracing-for-the-sluggard

https://www.royalacademy.org.uk/art-artists/work-of-art/tracing-for-the-sluggard

‘Private View at the Royal Academy’ and Frederic Leighton cabinet card at National Portrait Gallery, London

https://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/portraitExtended/mw00049/Private-View-of-the-Old-Masters-Exhibition-Royal-Academy-1888

https://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/portraitExtended/mw00049/Private-View-of-the-Old-Masters-Exhibition-Royal-Academy-1888

‘An Athlete Wrestling with a Python’, ‘The Sluggard’, ‘Needless Alarms’ plus ‘And the Sea Gave up the Dead which were in it’ at Tate

Keywords: Frederic Leighton, Gaetano Valvona, The Sluggard, Bronze, Sculpture.