Two Men and a Portrait

Posted on: 26 June 2020 by By Lorna Sergeant Collections and Exhibitions Officer in 2020

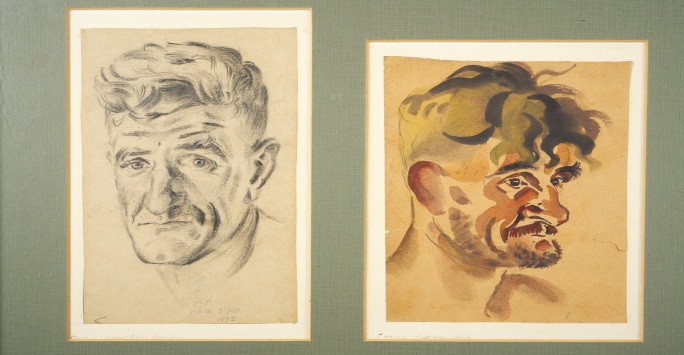

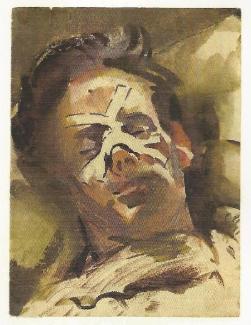

Two Portraits of Charlie Proctor, Changi 1942 & Thailand late 1943

By Gunner Ashley George Old, 1/5 Sherwood Foresters Regt.

Pencil on paper

Watercolour on paper

© the Bartholomew Family

I think this is one of the most arresting portraits in the exhibition, Secret Art of Survival - Creativity and ingenuity of British Far East prisoners of war, 1942 – 1945. It is a double portrait of the same man done by the same artist. It is a before and after portrait, something we are more familiar with today in a world of social media and photography. The portrait is of Private Ernest Charles Proctor, 1/5 Sherwood Foresters Regt, born in 1904 the oldest man in Old’s regiment at the time. It was drawn and painted by the artist, Gunner Ashley George Old. The pencil drawing on the left was done in 1942 during the first weeks of captivity in Changi POW camp in Singapore. The watercolour on the right was painted a year later in 1943 when both men were in the Chungkai Hospital camp in Thailand.

The difference between the two portraits is clearly evident. The pencil sketch on the left shows a man with a fuller, lantern-jawed, clean-shaven face. His head topped with thick hair that had probably been brushed back neatly at the beginning of the day. He fixes his steady gaze straight at the viewer, one bushy eyebrow slightly raised in an almost quizzical look. His lips drawn into a thin crooked line. You can tell from this portrait that Charlie is in a tough situation but he’s coping.

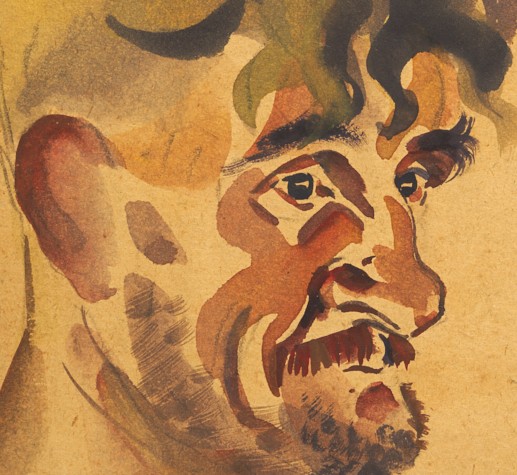

In stark contrast the pencil and watercolour portrait on the right shows a man who appears hopeless and detached. The flat wash of paint denoting the collar bone hints at the weight loss. The magnificent mop of sculpted unkempt hair, even bushier eyebrows and unshaven face, highlight the haunted feeling emanating from the portrait. The florid complexion and deep shadows depicted using underpainting particularly under the eyes show us how deflated Charlie is. Our attention is drawn to those deep black eyes, the slices of cream paper left untouched by black paint are used to make the eye more arresting and shinier, staring off away from the viewer.

The artist has depicted Charlie in a typical “thousand-yard stare” – a phrase often used to describe the vacant, unfocused look of infantryman who have come to be emotionally detached from the horrors around them. I think Charlie must have felt like this at this time.

Charlie Proctor detail 1943 Ashley George Old (b. 1913, d. 2001)

The artist Ashley George Old (b. 1913, d. 2001) was trained at Northampton College of Art and was taught anatomy by Lewis Duckett MC who had been an ambulance man in the First World War. After graduating he worked for the commercial art firm, Carlton Artists. He then returned to his studies in 1951 at the Camberwell School of Art.

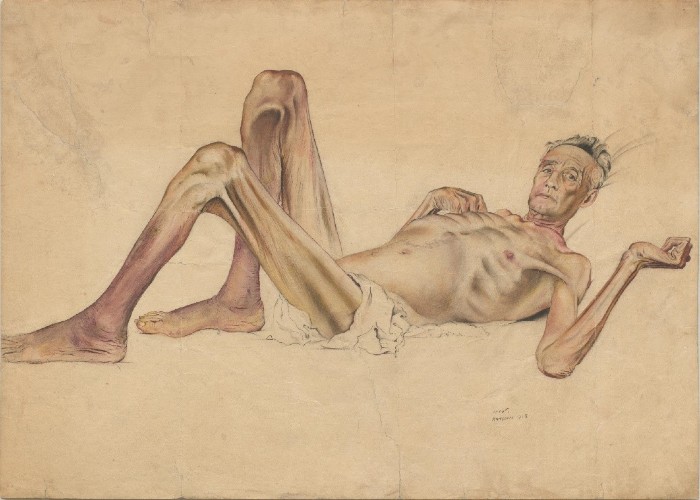

During the Second World War Charlie and Ashley (known as George) were stationed in Singapore. When it fell to the Japanese in February 1942 and after some months in Changi POW camp on Singapore Island, they were moved north to work on the construction of the Thai-Burma railway, otherwise known as the “Death Railway”. Old, having trained in anatomical art, worked very closely with the medical teams at Singapore’s River Valley Road and Changi POW camps, Chungkai POW Hospital camp in Thailand. Here he documented the horrific effects of untreated tropical diseases of his comrades and the ingenuity of the medical officers during captivity. The anatomical accuracy of his work can be seen below in this pencil and watercolour entitled, “Mr Stanley”.

Image courtesy of the National Army Museum, London.

Old painted Mr Stanley In Rangoon in September 1945. It is a painting that was not done in secret. Mr Stanley was probably in his 50’s and may have served in Malayan Volunteer Forces or he could have been a civilian internee hence his title Mr. Here, Old captures the exhaustion, emaciation and medical neglect Mr Stanley has suffered. The weakness is clear in the placidity of the hands, the haunted eyes and the line of his mouth, limp with resignation. A world-weary stoicism emanates from this precise anatomical painting of Mr Stanley. Something which can be seen in many of his portraits.

He created hundreds of portraits.

Old himself admitted that he had painted many hundreds of portraits during captivity. Some were buried in the ground and were recovered after the war. However, to date we only know the whereabouts of 18 of the portraits, mostly watercolours using pigments derived locally sourced laterite clay. This is rich in iron and would have been ground down and mixed with water to create the earthy palette of orange, browns and burnt umber typical in Old’s work. Old’s portraits are sensitively done and very beautiful even though the subjects are sometimes depicted injured, hurt and traumatised.

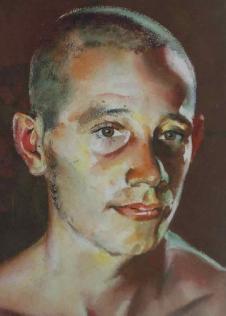

Private James Stinson, the youngest member 1/5 Sherwood Foresters, Changi 1942. © the Bartholomew Family

Miniature watercolour of Gunner Jack Chalker following a beating, having been found with drawings. Tarsao camp Thailand, late 1943. © the Bartholomew Family

He was known for working quickly and would often talk throughout the process of painting, describing what he was capturing as he worked. Stanley Gibson recalls in his diary held at the Imperial War Museum:

“As he works he keeps up a continuous monologue – “That’s excellent – interesting position that – now will get the eyes”. His work is splendid though doesn’t seem to be in keeping with his character. The watercolour he did today is a fine piece of work, but is too much glamorised. I wish I could send it home – it would dispense of all fear.”

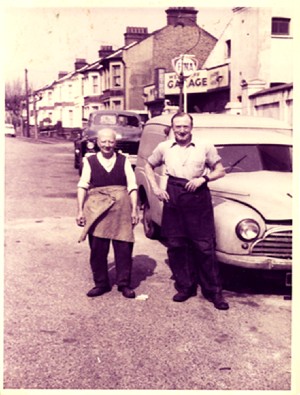

Both Charlie Proctor and George Old survived captivity. After the war Old went to live on Canvey Island, an Island of seven square miles lying off the South Coast of Essex in the Thames Estuary. Initially he worked in a hotel and then as a groundsman in the maintenance department of a factory. He continued to paint up to 1959 when his lasts series of landscape works were completed. He was passionate about his work and he recognised the importance of it. After 1959 it is understood that Old stopped painting, as he felt unable to continue due to the psychological trauma of his war years.

Ashley George Old (right) 1950's

Courtesy of the Bartholomew Family

It has been suggested by those who knew him that Old would have been a prestigious artist if his experiences as a FEPOW on the Thai-Burma railway had not left him so damaged.

You can see more artworks in the exhibition, Secret Art of Survival - Creativity and ingenuity of British Far East prisoners of war, 1942 – 1945. Old said he painted hundreds of such portraits during captivity. We know the whereabouts of 18 and hope to find more, can you help? Please contact the VG&M or visit www.captivememories.org.uk for more information.

Tomorrow will be Armed Forces Day an annual event celebrated in late June commemorating the service of all men and women in the British Armed Forces both past and present.

Keywords: A keyword.