Hero to Zero

Posted on: 31 July 2020 by Amanda Draper Curator of Art and Exhibitions in 2020

Dr Amanda Draper, Curator of Art & Exhibitions writes …

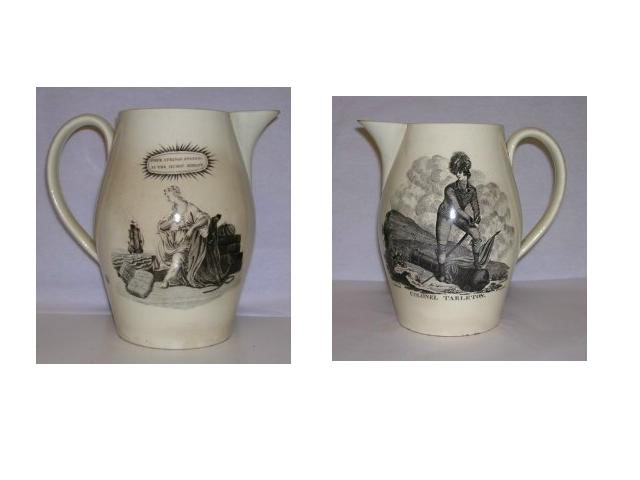

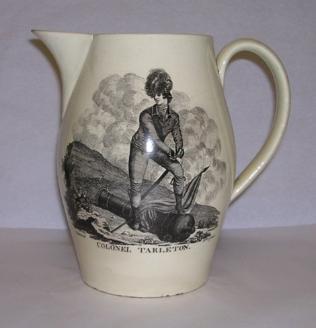

If working in a museum has taught me anything, it’s that history has different narratives which can change over time and one object can tell many stories. And so it is with this jug. It was created to celebrate military campaigns led by Colonel Banastre Tarleton, considered a hero in the 1780s. But time has reviewed Colonel Tarleton, his military career, his views on slavery and even his love life, and today he is perceived very differently. Let’s see how the jug tells these tales.

Banastre Tarleton (1754 – 1833)

Tarleton was born in Liverpool, one of seven children from the marriage of Jane Parker and John Tarleton. His unusual name came from his maternal grandfather, Banastre Parker of Chorley in Lancashire. On his father’s side, the Tarleton’s were Liverpool merchants going back several generations. As with so much of the mercantile wealth of the city, the Tarleton’s income was largely derived from the Transatlantic slave trade and this will be explored in more detail later. Aged 17, Banastre Tarleton looked set for a career in law and was attending University College, Oxford. But two years later he inherited £5,000 on his father’s death, worth about £440,000 today, which he burned through under a year with gambling and womanising. An army commision was purchased for Tarleton (possibly by his mother) as cornet, the lowest rank of cavalry officer in the 1st Dragoon Guards.

Tarleton and the American War of Independence

Aged 21, and still a cornet, Tarleton sailed to join the British forces fighting the American War of Independence. He was one of the party which captured General Lee in 1776. Promoted to Major, he was involved in key battles of the war including the Siege of Charleston. When Tarleton gets mentioned in history books, it tends to be for his part in the Battle of Waxhaws of May 1780. He was leading a force of mounted solders who defeated American troops led by Colonel Abraham Buford. Eventually Buford ordered his men to surrender and they raised a white flag. Tarleton and his forces ignored the clear signal of capitulation and continued their onslaught in what is now regarded as a massacre. Further battles and skirmishes continued until Tarleton was part of a British surrender at Yorktown in October 1781 which ended his involvement in the war. He departed America as a Lieutenant-Colonel but with a reputation there for ruthlessness and nicknames like ‘Bloody Ban’ and ‘Ban the Butcher’. But he was perceived differently in Britain.

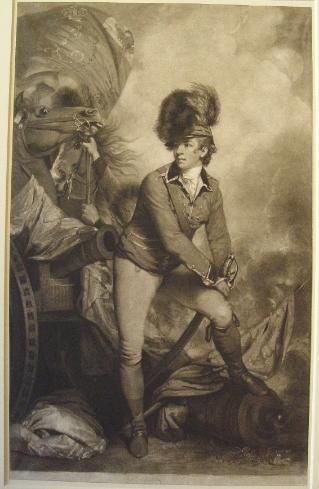

Colonel Banastre Tarleton by Sir Joshua Reynolds, 1782 (oil on canvas). Courtesy of the National Gallery, London

Tarleton the War Hero

Back home, Tarleton wrote an account of his war experiences justifying the Waxhaw incident and generally glorifying himself. As a measure of his heroic status, Tarleton’s portrait was painted by Sir Joshua Reynolds in 1782 and exhibited at the Royal Academy. Any painting which hangs in a Royal Academy exhibition gains prestige but Reynolds was its President, knighted for his services to art, and the leading portrait painter of his day. The painting seems to have been a commission paid for by Tarleton’s mother. Nonetheless the swaggering figure captured the public imagination. Tarleton is shown propped up on a cannon with gunsmoke in the background and wild-eyed horses to one side. He wears the tight breeches and high boots of a cavalry man with the green jacket uniform of the British Legion, the forces he led at the Battle of Waxhaws. A plumed hat falls rakishly over one eye. Indeed the hat was reputed to be of his own design and became known as the ‘Tarleton Helmet’.

Mezzotint print after the Reynolds portrait. Engraving by John Raphael Smith, 1782. © Trustees of the British Museum

Tarleton and his Jug

A mezzotint engraving of the painting was created by John Raphael Smith soon after the painting was displayed. Published copies would have been for sale in print shops and enabled the image to be widely seen. The jug features a simplified version of the portrait with background details omitted but the pose is recognisable. The transfer design is signed ‘J. Johnson’ and ‘Liverpool’. Liverpool was the centre for transfer-printed wares and the process is thought to have originated there in the 1750s. Once the transfer pattern had been designed, it could be printed and applied to blank wares relatively quickly and far more cheaply than hand-painting. It enabled producers to make a quick response to topical themes and cash-in on fleeting popularity. And so, being a ‘local hero’, Tarleton appears on jugs.

Tarleton jug, c.1783

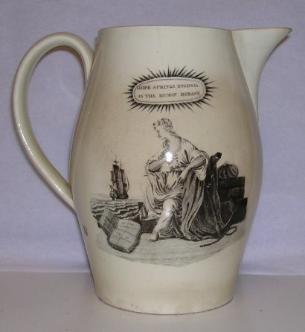

The other side of the jug shows a woman on a quay-side watching a ship sailing away with the words ‘Hope springs eternal in the human breast’ above. These are lines from the poem ‘An Essay on Man’ by Alexander Pope (1733-34). The design and sentiment were aimed at sailors and others passing through looking for souveniers to take home. It is likely this transfer pattern was used on several items and its twinning with Tarleton was chance rather than holding any special significance.

Hope springs eternal transfer print

Tarleton and Mary Robinson

Tarleton’s time in the public eye was prolonged through his love life. By September 1782, it was being reported in London newspapers that Tarleton had seduced Mary Robinson, a famous actress who had previously been the Prince of Wales’ mistress. She was enduringly linked to her most famous role as Perdita from The Winter’s Tale by Shakespeare. Most accounts say Tarleton seduced her for a bet, but the relationship endured for 15 years. Because of Mary Robinson’s notoriety the couple were followed by gossip and featured in scurrilous cartoons. To be fair to Mary Robinson, she possessed intelligence as well as beauty and became a respected writer.

Their relationship eventually ended in 1797, around the time that Tarleton fathered an illigitimate daughter named Banina with another (unknown) woman. A year later he married Susan Bertie (1778 – 1864), a much younger, wealthy woman who was the illigitimate daughter of the Duke of Ancaster. Like Robinson, she was an accomplished writer. They had no children but the unlikely match seems to have been a happy one.

Tarleton and the Slave Trade

Returning to the beginning of Tarleton’s story, he was born into a dynasty of merchants heavily involved in the Transatlantic slave trade. His father, John Tarleton, owned ships engaged in the slave trade and directly owned slaves at the Belfield Estate in Dominica. His grand-father, Thomas Tarleton, and his uncle, also called John, had made their fortunes trading in the West Indies and Africa. Banastre Tarleton’s brothers John, Thomas and Clayton all worked in the family firm and, between 1786 and 1804, had 39 ships registered to Liverpool. One of their slave transportation ships was called Banastre.

Although he was still technically in the army, Banastre Tarleton decided to become a politician and was eventually elected MP for Liverpool in 1790. He held his seat until 1812. He was a vocal supporter of the slave trade in Parliament, using his position to campaign against the growing abolitionist movement. He became known for his taunting and mocking of abolitionists. His vociferous support of the slave trade would have been fuelled by the demands of Liverpool’s merchant class and other stakeholders of the local economy who relied so heavily on it. Not least his own family.

Despite Tarleton’s efforts, the Act for the Abolition of the Slave Trade was passed in 1807 which made it illegal to engage in the trade or ownership of enslaved people throughout British colonies. The Slavery Abolition Act, outlawing the actual enslavement of people in British colonies, was passed by Royal Assent on 28 August 1833.

Hero to Zero

Banastre Tarleton died in January 1833. He’d been promoted to General and made a Baronet in 1812 and was still regarded as a hero by some, although his reputation suffered in some quarters over the slavery debate.

Since then the world has turned many times and we see things differently now. Tarleton’s role in the American War of Independence is largely fixed as ruthless and brutal. His treatment of women is shocking. His views on slavery, along with the actions of his family, appalls and repulses us. Hero to Zero.

All this history from just one jug.

Click below for more information on:

The portrait by Sir Joshua Reynolds

To find out more about the Transatlantic slave trade

To find out more about the Transatatic slave trade

To find out more about the Transatlantic slave trade