Bone of Contention

Posted on: 18 September 2020 by Leonie Sedman Curator of Heritage Collections & Lorna Sergeant Collections and Exhibitions Officer in 2020

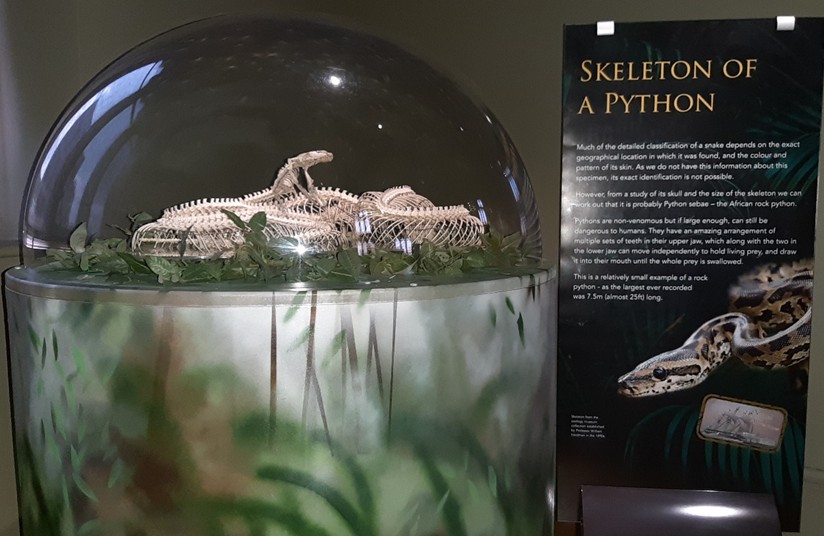

As you enter the Tate museum one of the first parts of the natural history collections that greets you is this incredible skeleton of a python. The museum has a large collection of natural history including full skeletons of mammals from gorillas to tiny mammal skulls, taxidermy teaching models and osteology teaching models (real skeletons prepared and articulated and mounted on wood). The python being the most intricate and impressive in my opinion of the teaching models deserves this week’s blog spotlight. You can look at it for a long time and marvel at the amount of bones a python skeleton has, work out how they function and move but what is incredibly striking is the workmanship in creating such a fascinating model, who made it and why?

How can you tell it’s a Python?

The snake teaching specimen display Tate Museum 2020

Firstly, our snake skeleton did not have a label when it was brought into the museum collection. It was obvious it was a snake but often you will be asked “What type of snake?”. Much of the detailed classification of a snake depends on the exact geographical location in which it was found, and the colour and pattern of its skin. As we do not have this information about this specimen, its exact identification is not possible.

However, from a study of its skull and the size of the skeleton we can work out that it is probably Python sebae – the African rock python. Pythons are non-venomous but if large enough, can still be dangerous to humans. They have an amazing arrangement of multiple sets of teeth in their upper jaw, which along with the two in the lower jaw can move independently to hold living prey, and draw it into their mouth until the whole prey is swallowed. This is a relatively small example of a rock python - as the largest ever recorded was 7.5m (almost 25ft) long.

Why do we have this in our collection?

The teaching specimens we have were originally part of the University of Liverpool’s Museum of Anatomy and Zoology established by Professors William Herdman and Andrew Melville Paterson. Initially the museum was created from the two professors’ personal collections of specimens. Over time they added to the collections developing a museum in the Derby Building of Anatomy and Zoology from 1901 onwards.

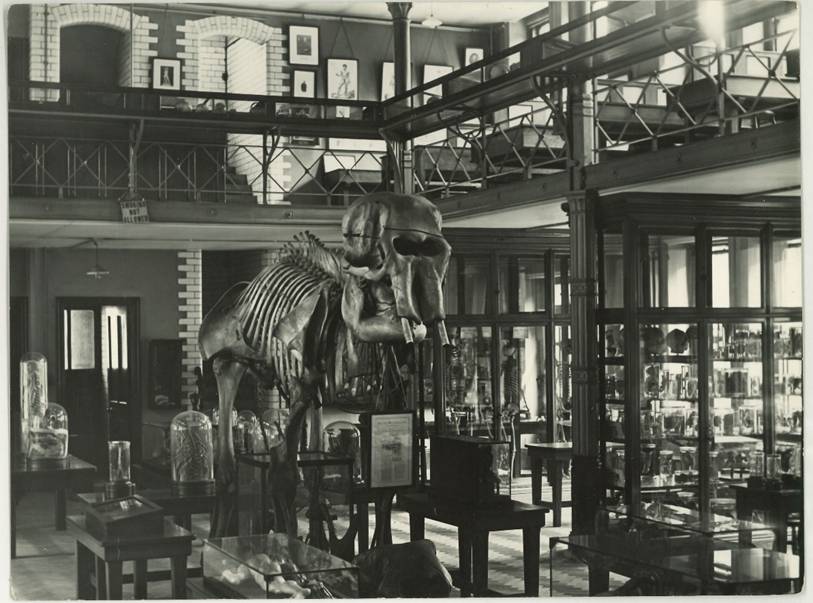

The Museum of Zoology and Comparative Anatomy, Derby Building 1901

The collections covered the research interests of both professors Zoology, Oceanography and Geology from professor Herdman and Human and comparative anatomy from Professor Paterson.

Professor Andrew Melville Paterson

Teaching models what are they and who made them?

Teaching models can be found in many university collections. Teaching models were used in comparative anatomy, dentistry, medicine and zoology some of the most notable teaching models are often made of wax and attract scholarly interest particularly if they are by a famous maker such as Ziegler. There were other companies that specialised in the making of teaching specimens and models who were using new technologies. One of these was a company called Edward Gerrard & Sons, a very successful firm which prepared specimens and created models for zoological study for over one hundred years.

Edward Gerrard was a naturalist and taxidermist, born in Oxford in 1811. He began working as the resident taxidermist at the British Museum in 1841. In 1853, whilst still working for the British Museum, he founded an independent taxidermy company with his sons.

Gerrard set up the family taxidermy and osteology business in workshops in Camden London. The Gerrard workshops became famous as a place where hunters, travellers, and naturalists exchanged or sold specimens. The proximity of London zoo and the veterinary college ensured a regular supply of dead animals. During the peak of British taxidermy, from about 1880 until 1914, Gerrard’s business thrived.

When Leonie Sedman Curator of Heritage Collections embarked on researching these collections she discovered a published history of the firm (P.A. Morris, Edward Gerrard and Sons: A Taxidermy Memoir, 2004). When studying the book, it became clear from photographs such as the one below that our snake was probably made by Gerrard and Sons along with other specimens in our collections that had long lost their labels.

Comparing these photographs of Gerrard’s staff members preparing snakes and how our snake has been prepared and articulated. We are almost certain that this company provided the university with this skeleton of the Python.

A Gerrard staff member articulates the snake head

© of Houlton-Deutsch/CORBIS

Preparing and articulating skeletons was a time consuming and skilled job. Bones were first cleaned, scraped of flesh, then bleached, the more thoroughly this was done then the more the bones separated and it then took much longer to put the skeleton back together. It was a difficult task articulating a skeleton, much like putting back together a three-dimensional jigsaw. Therefore, an exacting and detailed knowledge of anatomy was essential to discern the right and left components of the skeleton to attain a realistic posture. Above, a member of staff at Gerrard’s is positioning the snakes head.

A Gerrrad staff memebr cleans the flesh from a snake skeleton

© of Houlton-Deutsch/CORBIS

Snake model detail with wire

On the left a member of staff at Gerrard’s is stripping the flesh from a snake skeleton. Snakes have between 200-400 vertebrae with as many ribs attached. These would be difficult to re assemble and articulate if they became separated. Therefore, the vertebrate and ribs would be roughly cleaned then threaded onto a wire before the bleaching of the skeleton. The superior models like our model here has the bones set with wires whilst the cheaper versions were glued together. Snakes and fish were some of the most difficult models to prepare because they have so many bones. Birds were easier as they had fewer.

We have other teaching specimens in the collection that have the Gerrard labels intact including care labels on taxidermy teaching models.

Gerrard & Sons labels

The company continued throughout the 1950s but taxidermy become less fashionable and affordable for local authority museums. The business was split, one part continued producing taxidermy, on a much smaller scale, while another would hire out their stock to film companies. Not only did Gerrard supply universities with teaching specimens the workshops were frequented by producers for film sets (Alfred Hitchcock) and later television. The producers of the television sitcom show Steptoe and Son would often loan and buy specimens to dress the Steptoe set.

The firm continued until 1967.

Keywords: Gerrard & Sons, Osteology, Teaching Models, Taxidermy, Museum.