Liverpool and Manchester Railway

Posted on: 27 November 2020 by Amanda Draper, Curator of Art & Exhibitions in 2020

We are going to celebrate Lancashire Day with a look at a world-changing innovation that spans the historic county from one great city to another and is still used today: the Liverpool and Manchester Railway.

A hidden history

Sitting in our collection are a number of prints that might seem quite dull to the average viewer. They show petite Victorian figures with small locomotives puffing into view, set against often monumental architectural structures. But, if given a closer look, they reveal a fascinating glimpse of a pivotal moment in industrial development and a world first for our region. They show the earliest days of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway which opened on 15 September 1830 and was the first inter-city passenger and freight railway in the world, running a timetabled service and using carriages hauled by new-fangled steam locomotives. It heralded the railway age which, as well as moving people around more efficiently, transformed communication and the conveyance of goods, which in turn fuelled industrial growth.

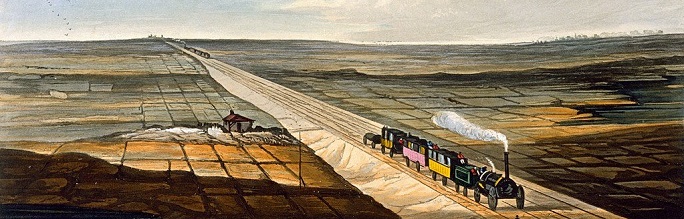

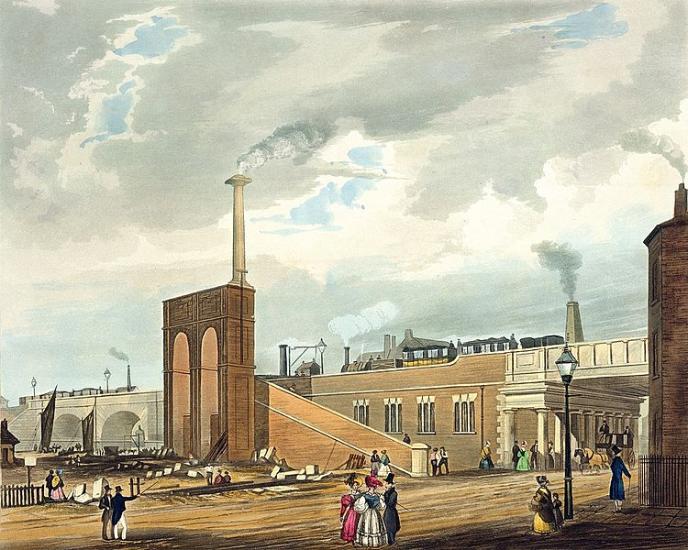

Warehouses &c at the end of the Tunnel towards Wapping, 1831.Engraved by S.G. Hughes after a painting by Thomas Talbot Bury

Origins

The North West was the hub of Britain’s industrial revolution. Liverpool was its main port, receiving raw materials for onward transit and then being the departure point for shipping manufactured goods across the globe. As the industrial heartland of the region, Manchester and its outlying towns were the key recipients of imported raw materials such as cotton, and so the major producers of the manufactured goods needing to get back to port. The problem was that travelling the thirty-one mile journey between the two cities was a choice between a twelve-hour canal ride or a perilous, jolting three hour-carriage ride along potholed roads. A group of enterprising businessmen from both cities came together to plan a third way using a brand-new mode of transport, resulting in the formation of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway Company in 1824.

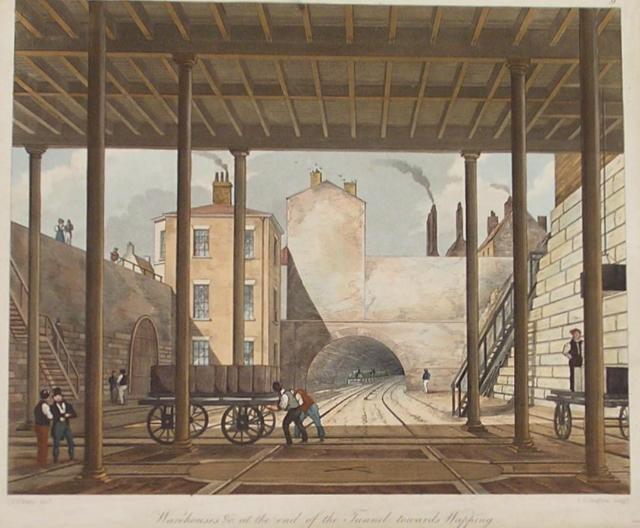

View of the Railway Across Chat Moss, 1831. Engraved by Henry Pyall after a painting by Thomas Talbot Bury

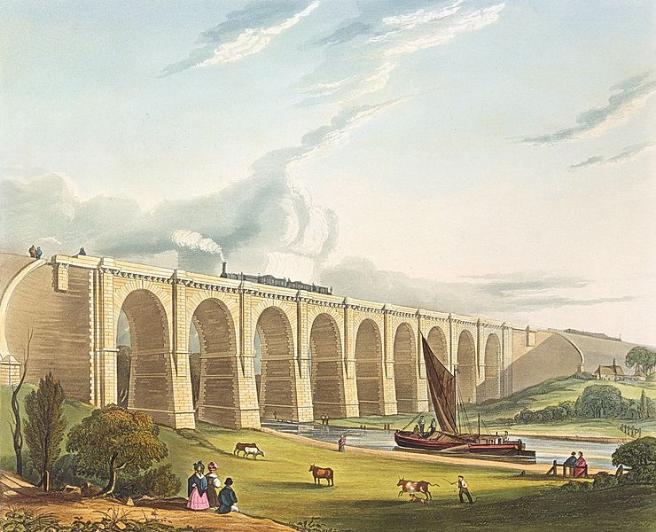

Soon afterwards the committee appointed George Stephenson as chief engineer of the project, although the construction was far from straightforward. Stephenson was dismissed, then re-appointed. There was opposition from land-owners with vested interests in other transport systems, especially canals, so the route had to be carefully planned to avoid their land. It needed sixty-three bridges and a viaduct across the Sankey Valley, a long and deep stone cutting at Olive Mount, a tunnel underneath Liverpool and an innovative way of supporting the tracks across the 4¾ mile boggy stretch of Chat Moss.

Rainhill Trials

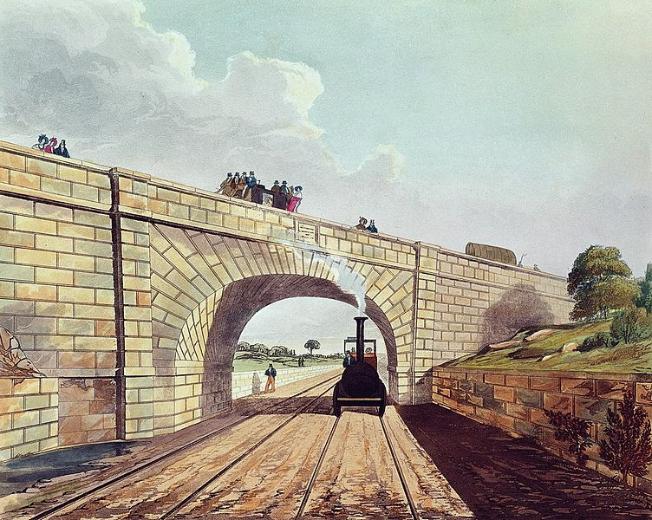

Rainhill Bridge, 1831. Engraved by Henry Pyall after a painting by Thomas Talbot Bury

There had been some debate about whether to use steam locomotives to actually pull carriages or the more tried-and-trusted method of cable haulage which used stationary engines and thick ropes to drag the carriages along. To see if steam locomotives were viable, a competition was arranged in October 1829. Five locomotives by different makers were run along a one mile stretch of the track at Rainhill in an episode which came to be known as the Rainhill Trials. Over 10,000 people came to witness the excitement. In the event, there was only one locomotive that successfully completed the trials but it proved locomotives were up to the job and so was the clear winner. It was Rocket, designed by Robert Stephenson, son of the railway’s main engineer. Stephenson junior’s company was awarded the contract to construct additional locomotives for the line and he won the prize of £500 (about £34,000 in today’s monetary value).

Grand Ceremonial Opening

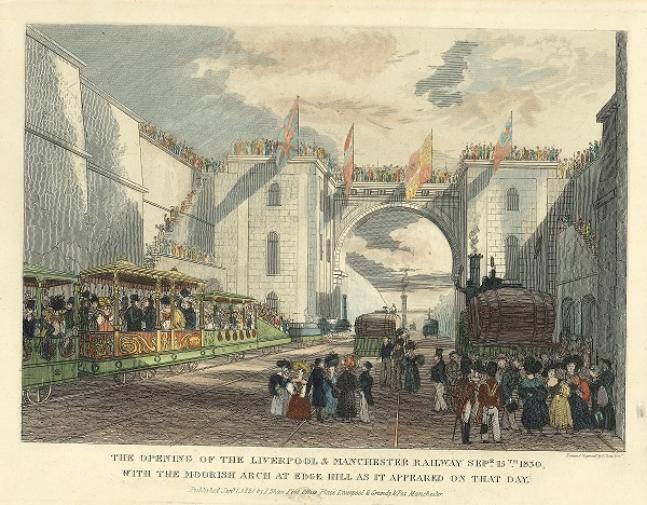

The Opening of the Liverpool & Manchester Railway Sept 13 1830, with the Moorish Arch at Edge Hill as it appeared on that day. Engraved by I. Shaw Jnr.

The Liverpool and Manchester Railway publicly opened on a rainy September day, six years after it had been first agreed. It had cost £820,000 to build (£55,600,000 in today’s monetary value) and the organising committee were intent on making a great spectacle of the day. A plethora of dignitaries, including Prime Minister Arthur Wellesley, Duke of Wellington, were arranged in eight trains each pulled by a locomotive. Rocket was one, and another was the Northumberland driven by George Stephenson which pulled the Prime Minister’s especially ornate and be-decked train. They departed from Liverpool’s terminus at Crown Street, technically the very first passenger station in the world, heading for Manchester’s Liverpool Street station at the other end of the line. Crowds packed into every conceivable viewing place at stations along the route to observe the momentous occasion.

William Huskisson by Richard Rothwell, c.1831 (oil on canvas, copy of earlier painting by the artist) NPG 21. © National Portrait Gallery, London

A Tragedy

One of the VIP’s riding on the Prime Minister’s train that day was William Huskisson (1770 – 1830), the MP for Liverpool. It had been agreed that the Prime Minister’s train would go on the south track and the other seven trains go along the north track. The locomotives needed to take on water about half way, so it had been arranged that they stop at Parkside station for a short break. All the passengers had been warned to stay on board but many on the Prime Minister’s train ignored the request and stepped down on to the track. Huskisson, who was recovering from an operation, was keen to speak with the Prime Minister because they had previously fallen out, which affected Huskisson’s place in the Government. He approached the Prime Minister and the two men shook hands. At that point, a shout went up that a locomotive (Rocket) was approaching on the other line. Those nimble enough scrambled back into their carriages while others pressed themselves against closed carriage doors to give Rocket enough clearance. Huskisson, who was still incapacitated from his surgery and known to be clumsy anyway, panicked. He ended up swinging on the Prime Minister’s open carriage door in front of Rocket. The driver tried to brake but the locomotive hit Huskisson, pitched him onto the track ahead and ran over him. Huskisson’s leg was horrifically mutilated and he died later that evening as a result of his injuries. It gives him the tragic position of being the first person in the world to die in a rail accident.

It was decided to continue with the scheduled run into Manchester but the mood was now very subdued.

-635x515.jpg)

Taking on Water at Parkside, 1831. Engraving by Henry Pyall after a painting by Thomas Talbot Bury

Railway Mania

Huskisson’s death could have had a serious impact on the public’s perception of this new mode of transport as too dangerous to be used. But the opposite happened. Within a month about 1,200 passengers per day were travelling the route, with a journey time of about two hours, and it was a huge financial success despite charging half the price of going by stage-coach. Its immediate success gave rise to a period known as ‘Railway Mania’ when thirty-five major railway lines were built across Britain during a fifteen-year period, and it spread to hundreds of new railways being built around the world.

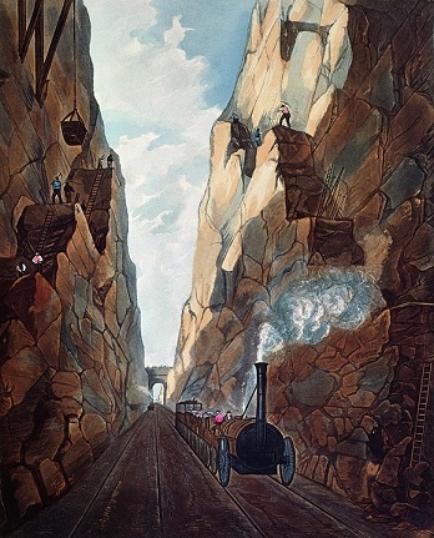

Excavation of Olive Mount, 4 Miles from Liverpool, 1831. Engraved by Henry Pyall after a painting by Thomas Talbot Bury.

The Prints

So amazed were people by this incredible feat of engineering that they wanted pictures of it to study at home. Most of the related prints in our collection were from a set called ‘Coloured Views on the Liverpool and Manchester Railway’ published in 1831 by Rudolph Ackermann, a highly successful printmaker and publisher based in London. The artist was Thomas Talbot Bury (1809 – 1877), who created a series of watercolour paintings showing the most spectacular aspects of the Liverpool and Manchester line. According to its byline, the paintings were ‘From drawings made on the spot” by the artist, and were to serve as a guide to travellers.

Viaduct across the Sankey Valley, 1831. engraved by Henry Pyall after a painting by Thomas Talbot Bury

Bury trained as an architect apprenticed with Augustus Charles Pugin, and he later collaborated with his tutor’s son, Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin, on his Gothic Revival decoration for the Houses of Parliament. Bury set up his own architectural practice in 1830, and his professional interests have influenced the way that the prints look, with an emphasis on the grandeur of buildings and man-made structures while putting in figures more to give scale rather than add any narrative to the scene. As well as an architect, Bury was a skilled print-maker who specialising in lithography. But to turn Bury’s paintings into print reproductions it was decided to use the slightly old-fashioned method of aquatint, a technique using acid to create etched areas on a metal plate to give shading when inked up, with additional hand-colouring to the finished print. Rather than doing the print process himself, this highly-skilled work was allocated to Henry Pyall and S.G. Hughes who are credited in the corner of the published prints as ‘sculpt’. As with the railway itself, the prints were a huge success and the series underwent many reprints.

Entrance into Manchester across Water Street, 1831. Engraved by Henry Pyall after a painting by Thomas Talbot Bury

A Chance to Visit the Past

For anybody wishing to see for themselves what life was like for those first passengers on the Liverpool and Manchester Railway, I urge you to visit the Science and Industry Museum in Manchester which is housed on the site of the Liverpool Road Station, and where you can step inside some of the original 1830s buildings. It was the starting point of many an historic journey, including my own, and was where I first worked as a museum curator over twenty years ago.

Further information

Science & Industry Museum, Manchester (please check website for current opening information)

https://www.scienceandindustrymuseum.org.uk/

https://www.scienceandindustrymuseum.org.uk/

History of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway

https://www.scienceandindustrymuseum.org.uk/objects-and-stories/making-the-liverpool-and-manchester-railway

https://www.railwaymuseum.org.uk/objects-and-stories/stephensons-rocket-rainhill-and-rise-locomotive

Note.

Due to COVID-19 lockdown it was not possible to access and photograph our series of Ackerman prints, so the illustrations of these have been downloaded from other publicly available sources under Creative Commons licenses. The Shaw print illustrated is from our collection.

Keywords: Liverpool and Manchester Railway , George Stephenson, Robert Stephenson, William Huskisson, Rainhill Trials, Parkside Station.