Liverpool by Tony Phillips

Posted on: 30 October 2020 by Amanda Draper, Curator of Art & Exhibitions in 2020

A young girl looks up at one of the famous stone lions outside St George’s Hall in Liverpool. How does she and the lion represent our city’s past and hopes for the future? Let’s look closer at this painting by Liverpool-born artist Tony Phillips and find out more.

Tony Phillips: Liverpool, 1995 (oil on canvas, 157.3cm x 121cm)

Origins of the painting

The painting was created as one of a group of three works each depicting a major international city: Paris, New York and, of course, Liverpool. The trio were devised for a touring exhibition curated by the city’s Bluecoat Gallery in 1995 called ‘The City’. ‘Liverpool’ was purchased from the artist in 2006 for the University of Liverpool’s permanent art collection.

The composition of the painting is ingenious and allows the artist to introduce an historical narrative alongside socio-political themes, a recurring aspect of his work. The upper part of the composition is divided into three sections, separated by the vertical poles of bus-stops that perhaps signal the city’s long historical journey. To the left we see grand buildings representing the city’s wealth with tiny red-brick terraced housing and industrial buildings of its Victorian past crammed together at the top. To the right we see those red-brick Victorian building in ruins as concrete high-rise blocks clamber upwards representing the present as an unstable dystopian jumble.

-577x671.jpg)

Detail of top left of painting showing Victorian red brick buildings

-605x687.jpg)

Detail of top right of painting showing modern high-rise buildings.

The Girl and the Lion

The central section featuring the young girl and the lion is the real focus of our attention. Tony Phillips describes what he is depicting:

The work features a mixed-race child (typical of the Liverpool I grew up in during the 1950s) confronting the majesty of one of the lions that adorn the square in front of St George’s Hall. The power of the stone sculpture embodies the might of British Empire, establishing an authority over the bemused child, at once threatening and paternalistic.

The lion itself seems benign, even friendly, if somewhat pockmarked and worn with the faintest touch of green moss dusting its nose. But it’s the sheer scale and mass of the sculpture in comparison the delicacy of the young girl that makes a clearly uneven pairing. Tony further explains how for him the lion is a symbol of the “hierarchical order of the environment in which she is growing up”. However, the lion is just an immobile stone statue, whatever its emblematic significance, whereas the child is a human being with the opportunity to make a difference to the future. For Tony, “the confrontation is a momentary phase in the formation of the human she will become”.

Stone Lions guarding the Plateau, St George's Hall (©Karl and Ali, licensed under Creative Commons). They are by sculptor William Grinsell Nicholl (1796 – 1871) and date from 1855. The Hall itself opened the previous year.

Dock Wall

Underneath the stone lion and the young girl, propping everything up, is the sea wall and barnacle-encrusted chains of Liverpool Docks. For Tony, the dock wall symbolises the history of the city and how it was founded. He tells us:

Here the sweat and toil of thousands of labourers, dockworkers, seafarers, entwined with the suffering of slave transportation is silently etched, relics of chains, detritus from vessels, semi-obscured under the surface of the River Mersey – dull remnants of their own sad history.

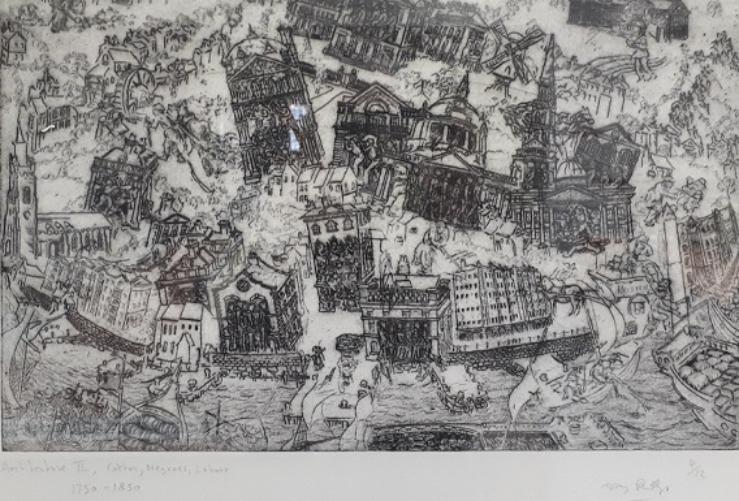

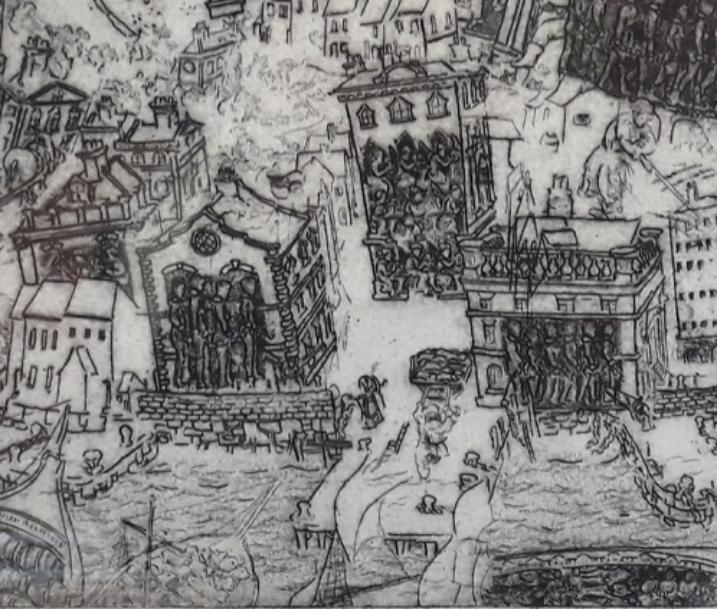

Tony returned to the dock wall in his 2003 etchings Architecture I, II and III which are part of a series of twelve etchings called Liverpool – Growth of a City, again in the University’s art collection. Architecture II (below) shows the city during the height of the industrial revolution, with grand civic and commercial buildings appearing to be shored up by the dock wall running along the bottom quarter of the composition, preventing them from tumbling into the Mersey. The city’s debt to its labouring classes and the slave trade is made apparent in the image as figures haul carts laden with goods up the streets, while others load and unload boats. The buildings are crammed with enslaved Black figures in shackles and chains, making a clear reference to the origins of the wealth that created the structures.

Detail from Architecture II: Cotton, Negroes, Labour 1750s - 1850s

Close-up detail from Architecture II showing enslaved people in buildings

About the artist

Tony Phillips is an artist whose work illustrates how important the past is to the present and the long shadows it casts over us all. Born in Liverpool in 1952, he graduated from Lancaster College of Art in 1972 where he specialised in mural painting and relief sculpture. As Tony developed and honed his artistic techniques, his work has often taken the form of a series, incorporating social and political themes within an historical narrative. Tony has exhibited widely across Britain and internationally.

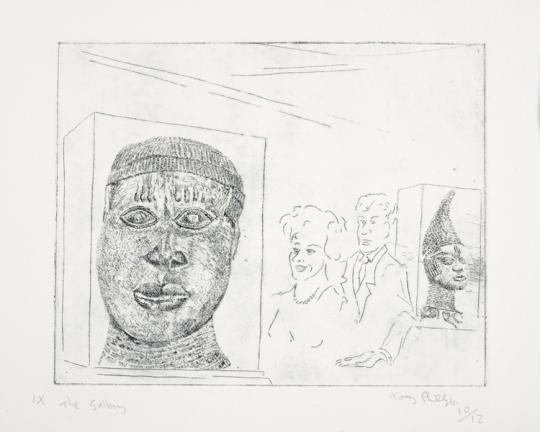

History of the Benin Bronzes Series

Although Tony uses a broad range of media he is perhaps best known for his etching which he developed during the 1980s. One of his most famous works is his History of the Benin Bronzes series of 1984, which illustrates twelve episodes from the capture of beautiful, elaborate bronze and brass sculptural art from Benin city (now part of Nigeria) in West Africa by British forces in 1897, and their subsequent dispersal to the British Museum and other Western institutions. The series acts as a commentary on British imperialism, but also on the disparity between the way the West perceived African peoples as ‘primitive’, and therefore self-justified their subjugation, and yet put their cultural artefacts on display as something to be admired. In the tenth etching from the series, The Gallery (shown below), two of the sculptures are shown looking trapped under glass; displayed for the pleasure of museum visitors but completely divorced from their cultural and historical context. One looks out at the viewer as though calling for help. Editions of this print series can be found in several public collections including the V&A and Arts Council. The Benin Bronzes themselves remain contentious with ongoing calls for their repatriation.

The Gallery, no 10 in the History of the Benin Bronzes series (Image courtesy of Gallery Oldham)

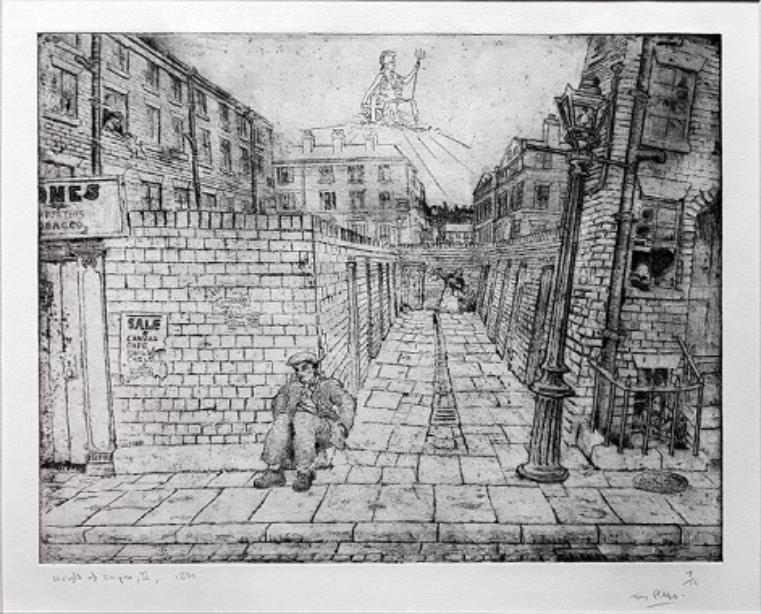

Liverpool – Growth of a City

The University is fortunate to have Tony’s Liverpool – Growth of a City series of etchings that demonstrate his unusual ‘single plate’ etching technique particularly well. He uses one plate, creates an image on it, then runs off a number of prints from it to create the edition.

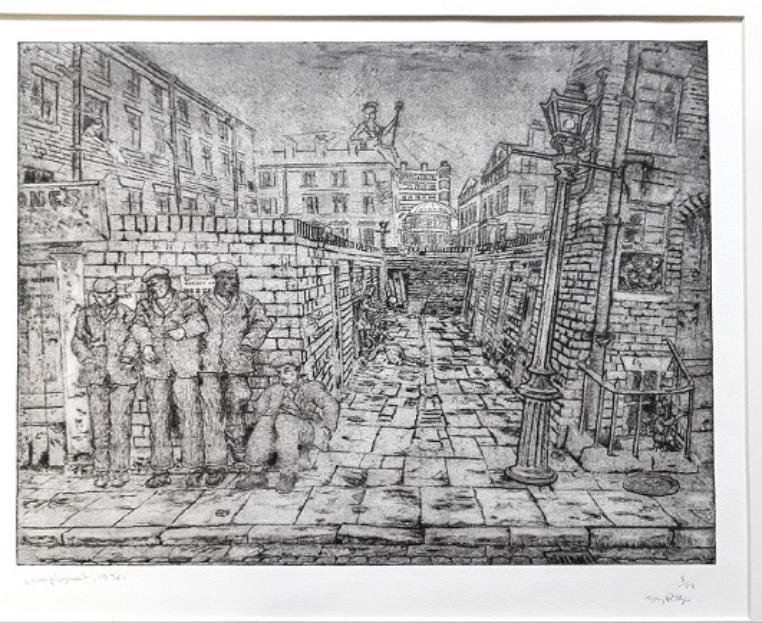

Height of Empire I, 1890s

He then re-works the same plate to create a second image by keeping the basic background scene but with some additions; retaining some figures while scoring out others or adding new ones.

Unemployment, 1930s

He then runs prints from this version before returning to rework the plate a third time.

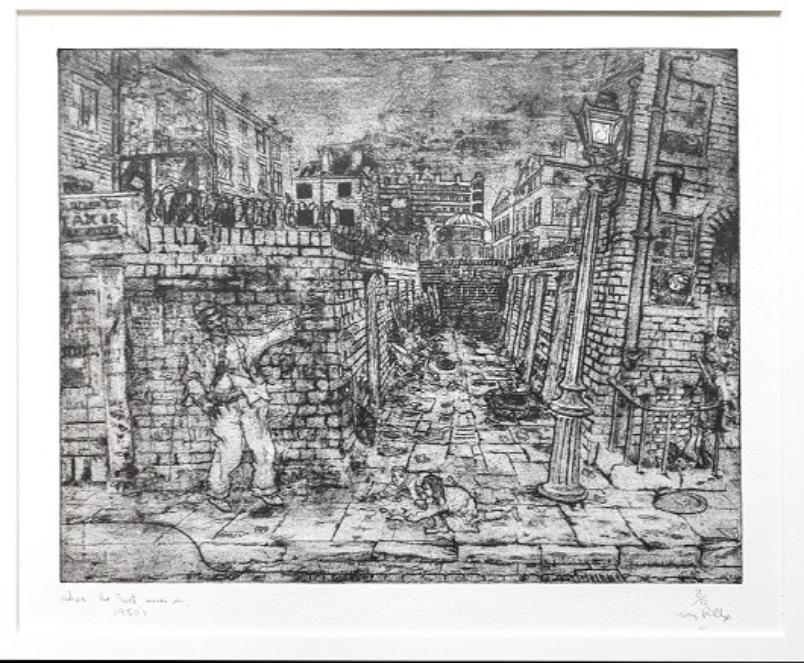

When the Boat comes in, 1950s

Tony will do this over and over with the same plate until the series he envisaged is complete. What he achieves is the impression of a build-up of history materialising as the series progresses. There are ghosts of the past and the accretion of history perceived through layers.

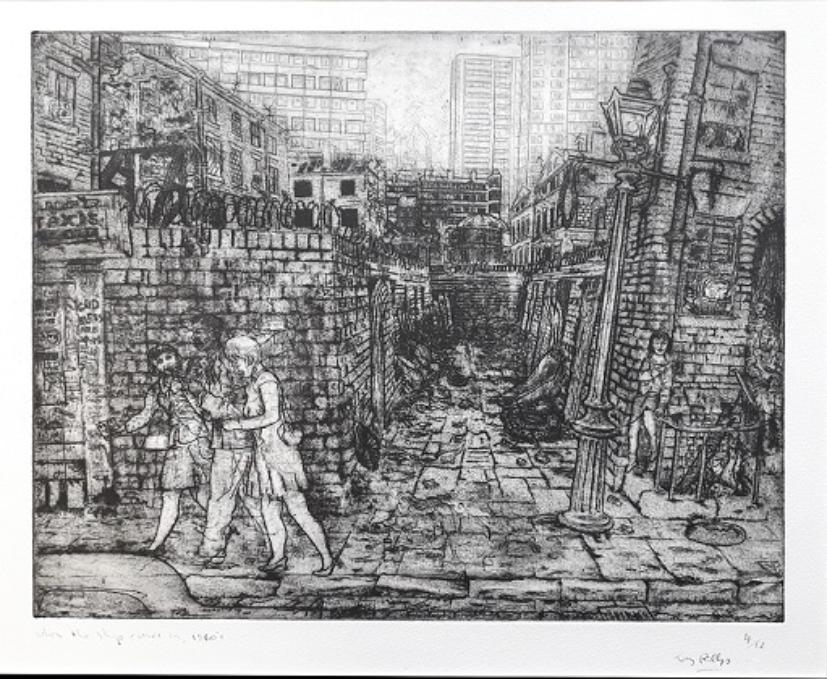

When the Ship comes in, 1960s

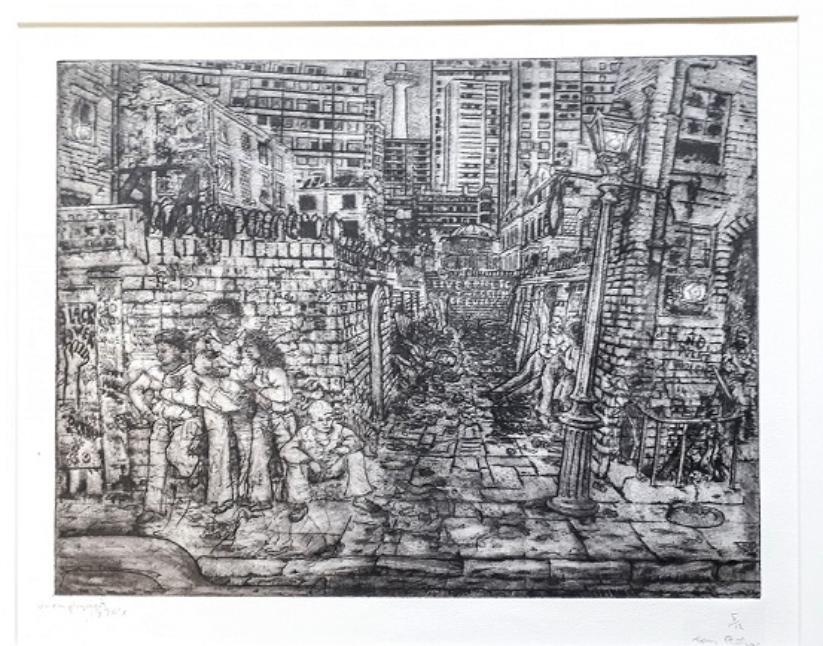

What we see in this six-print section of the Liverpool – Growth of a City series is a back alley in the multi-cultural Liverpool 8 area and how it changes from the 1890s to the 1980s as the city’s economic fortunes rise and fall, and the impact this has on the working-class people who live there. The immediate street-scene remains basically the same, but we see the city rise up in the background to a claustrophobic degree and detritus accumulate as the years go by.

Unemployment, 1970s

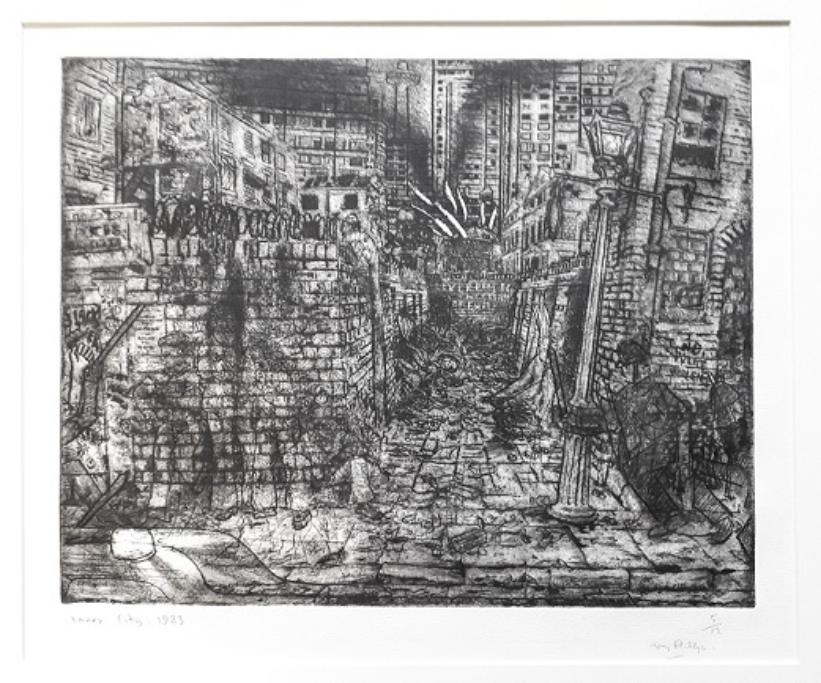

Inner City, 1980s

The six prints culminate with the city aflame during the unrest of the 1980s.

Both this series of etchings, and the painting of Liverpool we began with, offer a recognition of the city’s turbulent history and the blood, sweat and tears on which it was built. But there is also optimism for the future. Of the painting, Tony concludes:

[It is] in fact a tribute to a seafaring town, strife and suffering built upon a river engenders the growth of buildings – municipal wealth on one side, working-class estate on the other. The Liverpudlian child the unique spirit of mixed-race post war Britain.

Further information:

See more of Tony Phillips’ paintings on Art UK

Future Tony Phillips projects at The Bluecoat

http://www.thebluecoat.org.uk/events/view/exhibitions/4072

http://www.thebluecoat.org.uk/events/view/exhibitions/4072

Tony Phillips’ History of the Benin Bronzes etchings

http://revealinghistories.org.uk/colonialism-and-the-expansion-of-empires/articles/a-history-of-the-benin-bronzes-by-tony-phillips.html

http://revealinghistories.org.uk/colonialism-and-the-expansion-of-empires/articles/a-history-of-the-benin-bronzes-by-tony-phillips.html

For more information about the transatlantic slave trade:

Notes:

1. Six of Tony Phillips’ etchings for the Liverpool – Growth of a City series are displayed in the University’s Harold Cohen Library. They and the other works by the artist in the University’s collection are available to view by appointment.

2. The University of Liverpool was founded in 1881. We are aware that, as a civic institution created in one of the centres of Britain’s eighteenth and nineteenth century economy, and a seaport, the legacies of slavery and colonialism form part of our story. We are about to enter into a period of reflection through which we will consider, in consultation with our members and local communities, how we might appropriately recognise

Keywords: Tony Phillips, Liverpool, St George's Hall, Lion Sculpture, Benin Bronzes, Etching, Oil Painting.

-552x730.jpg)