The Remarkable Mrs Horsfall

Posted on: 20 August 2021 by Andrew Williams, Collections Assistant in 2021

On 6 July 2000, after 93 years of life, Mrs Betty Horsfall died at her home in Aylburton, Gloucestershire. She left, in her legacy, a substantial contribution to the University of Liverpool, which has enriched many people’s lives without their ever knowing it. She was, in life as in death, a remarkable person.

Betty Fairfax Rushby was born on 3 December 1906 in Marylebone, London, the younger daughter of Frank Rushby and Nellie Phillida (née Jerrard). Frank was a company director at his father-in-law’s business, Jerrard, Darby, and Clegg, trimming manufacturers. He had married Nellie in Brighton in 1896, and already had one daughter: Beatrice Phillida, born 1897. Frank’s origins before Brighton are murky, and censuses variously give his birthplace as Doncaster, York, and Manchester. In his obituary he was described as a “Yorkshireman,” but the truth is that he was born in Manchester to Elizabeth Rushby, who was not married at the time, on 26 December 1864. As Professor Ginger Frost has written, “Through the late Victorian period to World War II and even beyond, bastardy was a serious stigma legally, socially, and emotionally.” This, therefore, explains the abnormalities in official documents – it was likely the result of a subtle effort to save grace by Frank and his family.

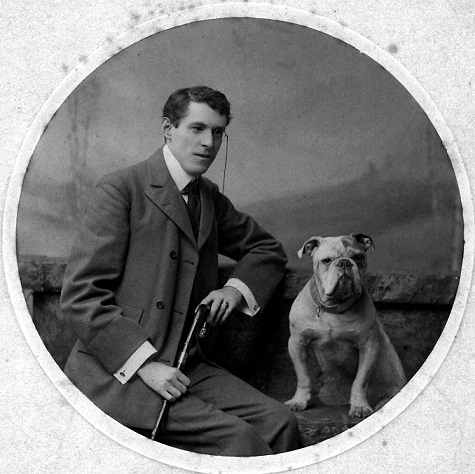

Portrait of Frank Rushby, from The Reading Standard, 6 March 1915.

Frank’s grandfather was a stonemason, giving no obvious indication of how he came into the wealth he eventually had. In the early 1870s, his mother married Richard Martley, although it doesn’t appear that he was Frank’s biological father. Likely as a result of the marriage, Frank was baptised in York in 1874, at age nine. The family grew up in Doncaster. Martley, who was from County Meath, was a merchant’s draughtsman, although later in his career he became a mechanical engineer. His contacts may have given Frank a head start, as in the 1881 census he was recorded as a banker’s apprentice. Ten years later, he was living in Norwood Green, London, with two domestic housekeepers. Evidently, he had become wealthy, either from banking or from his new occupation: commissions agent. Typically a ‘commissions agent’ meant an insurance broker, although it was sometimes used on documents as a euphemism for a bookmaker, which was still illegal at the time and would be until 1961.

After moving to Brighton and marrying Nellie, Frank joined the local militia in 1901, rising to the rank of Captain in the 1st Sussex Royal Garrison Artillery (Volunteers). It was at this time that he began collecting art, furniture, glassware, ceramics, and many other things besides. Victoria Gallery & Museum holds 107 receipts for various purchases by Frank between 1898 and 1910. His collecting at this time, which may have started earlier and presumably continued until his death, forms the bulk of what Betty Horsfall left to the University’s art collections in 2000. Among the receipts is one that describes two snuffboxes in racist language. It is probable that one of these is now in the University’s collection, which Dr Amanda Draper wrote about last year in a blogpost.

Arthur Dudley Yorke was a godfather of Betty Horsfall, but he died young in 1910, leaving her a large walnut bureau and a red lacquer desk.

Frank left the militia in 1905 and the family moved to the Little Deanery, Sonning, near Reading. The Rushbys didn’t stay in the house long – which was designed by Sir Edward Lutyens and is now owned by Jimmy Page, guitarist of Led Zeppelin – before moving again, around 1910, to nearby Erleigh Court. At Erleigh, Frank and Nellie came into their own, socially. They hosted fetes for the local Conservative Party, and Frank became chairman of Reading’s Wellington Club. He joined the Royal Field Artillery at the start of the First World War, serving with 98th Brigade, 22nd Divisional Artillery, but he never saw action before dying of pneumonia at his home in February 1915, leaving a total estate of £31,359.

The sudden death of her father led Betty and her widowed mother to move to Ravenglass, Cumberland. She became heavily involved in mountaineering and winter sports, and frequently travelled up to the Cairmgorns in Scotland. In 1933, she was credited with leading a rescue party from Braemar in search of two missing men in the Scottish mountains. An Aberdeen Press and Journal article titled ‘Woman’s Initiative’ noted her role: “That a search was made from the Braemar end was, in the first place, due to the courage and resource of Miss Betty Rushby [...] an experienced mountaineer, and the organiser of outings on the mountains and of winter sports at the Fife Arms Hotel, Braemar.”

Caption: Betty Rushby (second from left) enjoying winter sports with friends in the Cairngorns. Image from the Dundee Courier, 20 January 1933. © DC Thomson & Co Ltd, via British Newspaper Archive.

At the time of the 1939 England and Wales Register, taken just before the outbreak of the Second World War, Betty and her mother were still living in The Walls cottage in Ravenglass. Living with them were three Jewish refugees: Richard Kandelmann and his mother Anna from Austria, as well as Heinrich Kornstein from Poland. Richard later served in the British Army and Heinrich married Richard’s sister, Karla Lea, in 1942. Both the Kornsteins and Kandelmanns settled in Tennessee and Kansas in the United States after the war.

Also lodging was Ewart Douglas Horsfall, whose occupation was inconspicuously listed as “retired farmer.” Ewart was actually a former Olympic athlete, who had won Gold in the rowing in 1912, and Silver in 1920. A descendent of the wealthy Horsfalls of Liverpool, he was educated at Eton and Magdalen, Oxford, and served in the First World War as a pilot, winning the Military Cross and Legion d’Honneur. Betty became his second wife in 1946: he had married before in 1923 and had three children before divorcing. The Horsfalls of Liverpool were descended from Charles Horsfall, an enslaver who went on to pioneer Liverpool’s “legitimate” trade with Africa after the abolition of the slave trade in 1807. Primarily, Horsfall was trading in palm oil, produced in Africa under harsh labour conditions or even by enslaved people. During the 1850s and 60s, Horsfall was Britain’s largest oil importer, according to Martin Lynn’s 1992 article. The vast majority of collections given to the University by Betty Horsfall are those purchased by Frank Rushby, not inherited from her husband’s family.

Ewart Horsfall died in 1974, and Nellie Rushby also in 1979. After this, Betty moved to The Mill House, Aylburton, Gloucestershire, and decided that she would donate a large portion of her estate to the University of Liverpool on her death – the city where her late husband had come from. She turned her mind to botany, a subject she had been denied the opportunity to study when she was young. Between 1974 and 1990, she went on 17 visits to the Soviet Union to collect plant specimens and seeds. She took the director of Ness Gardens, Peter Cunnington, on a botanical expedition to Central Asia in 1979 and the deputy director, Hugh McAllister, to Russia in 1990. She wanted Ness to rival Kew in introducing plants from the wild. Her legacy can be seen all over Ness, and in other gardens such as the Welsh National Botanic Garden and the Glasgow City Botanic Garden.

Hugh McAllister recalls that she liked to be called ‘Tinge’ (Ewart’s nickname was ‘Dink’): “On the 1990 trip she was very quiet and never spoke to the group as a whole, but she often gave me advice about behaviour (helpful in dealing with interpreting others and understanding what was going on) and comments on other members of the group. I believe she spoke Russian quite well – but she never let on how much she understood […] Mrs Horsfall was a very strong character with very decided opinions and made her own judgements, she just didn't generally express them and could appear as a typical ‘little old lady’. I suspect she worried about not being allowed to do things (like going on the rickety floating boards to the ship the Angara) but was always game to try, and I felt my job was to help her.”

Among the plants that were brought back from that expedition were several Mongolian oaks (Quercus mongolica), Manchurian walnuts (Juglans mandshurica), an Amur cork tree (Phellodendron amurense), Scots pines (Pinus sylvestris var. mongolica), Siberian rowans (Sorbus sibirica / aucuparia) and birches (Betula pendula, B. pubescens), all still surviving. She went on annual visits to Ness after the 1990 expedition, often with her friend Larry Rathbone.

Some of Betty Horsfall’s plants in Ness Gardens. From left to right, Phellodenron amurense, Quercus mongolica, and Colutea arborescens, the latter of which has since died. Photos courtesy of Tim Baxter.

After she died in 2000, money from her bequest went on to fund the Horsfall Rushby Visitor Centre at Ness, which opened in 2006. In addition, many of the 190 items donated to the University’s art and heritage collections – the Mrs Betty Horsfall Collection– have been exhibited in the last two decades. Hugh McAllister, writing in the Ness Gardens newsletter in 2012, has the final word: “The overall impression I was left with, from the contact I had with her, was that we were very lucky at Ness to have had the interest and support of a plant lover who showed a true allegiance to both horticulture and botany. The plants from Russia still cared for and treasured at Ness are a simple but fitting tribute.”

Further Information

For more information about giving legacies to the University of Liverpool, please visit the University of Liverpool website.

Ness Botanic Gardens is located on the Wirral peninsula and is open to visitors.