How Gogglehead got his gleam back

Posted on: 3 September 2021 by Amanda Draper Curator of Art and Exhibitions in 2021

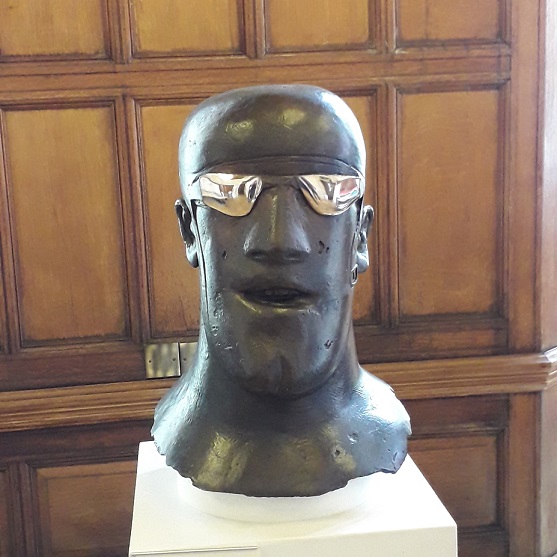

Larger than life, this disembodied head with its sardonic grin has been a VG&M visitor favourite for years. But most didn’t realise that his sunglasses were nowhere near as shiny as they should be. This is the story of how Gogglehead got his gleam back.

Gogglehead displayed in an exhibition in 2018

Gogglehead gets moved around a bit for different exhibitions, but he spends most of his time to the side of the lift on the first-floor for everybody to admire. He’s been in the University’s art collection since 1969, when he was purchased from the prestigious Waddington Galleries on London’s Cork Street. He is by the internationally famous sculptor, Dame Elisabeth Frink RA (1930 – 1993), who produced several series of these large heads, each in a small edition. Our is 6 of 6 and is dated 1967.

Gogglehead 1969 & recent photo

Why Gogglehead’s glasses grew dim

This black and white photo (above left) shows Gogglehead around the time he left Frink’s studio in the 1960s. You can see how shiny his sunglasses were at the time because there is a small figure reflected in the left lens who is likely to be the photographer. By the time he went on display in the VG&M in 2008, when the building first opened as a museum, his glasses had tarnished and didn’t stand out from his face in the way that they should. It was simply natural oxidisation of the metal over time, perhaps exacerbated by the sculpture being touched by visitors and the acidic secretions from fingertips that they leave behind. That is why museums ask you to look but not touch artworks.

Conservator Sally Bowling at work

Conservation

What was needed was the careful touch of a glove-wearing conservator. And luckily, we know an expert metal conservator called Sally Bowling who came along to give Gogglehead’s glasses a polish. After doing a few trials on test patches to check what might be the best approach, Sal got to work. She had determined that the bronze of the glasses had never been lacquered to prevent tarnish, just polished. However the tarnish was very thick leading us to assume that the glasses had not been cleaned since the sculpture was new. It was, said Sal, “some of the stubbernist tarnish I’ve ever seen”.

Some tools of the profession

Sal brought with her the tools of her profession and they were not, in this instance anyway, as high-tech as you might imagine. Her magic ingredient was Autosol metal polish, available from all major car accessory retailers she assured me. Good for chrome, aluminium, stainless steel, brass, copper and important bronze sculptures. Sal applied it in small circular motions with her custom swab sticks comprising a wad of cotton wool wrapped around the end of a kebab stick, replacing the cotton wool frequently as it took off the dirt.

Gogglehead half done

At the half-way stage, with one lens done, there was a remarkable difference. I’d checked through our archive records on the sculpture and consulted records of the other editions of the sculpture to check exactly where the glasses were supposed to be shiny and where matt. It was just the lenses, with the central bar and side-pieces left with the darker patina.

A last check

After a final scrutiny with her UV torch to make sure all the tarnish had been removed, Sal went in with her finishing touch. She cleaned off the surplus grease from the Autosol with acetone, handily available from your local chemist or general store in the guise of nail varnish remover. A quick buff with a micro-fibre cloth and Gogglehead was back to his gleaming best. Thank you Sal!

Shiny goggles again

A group of us had gathered watching Sal at work, and it was generally agreed that Gogglehead looked a lot cheerier and was smiling more widely after his clean.

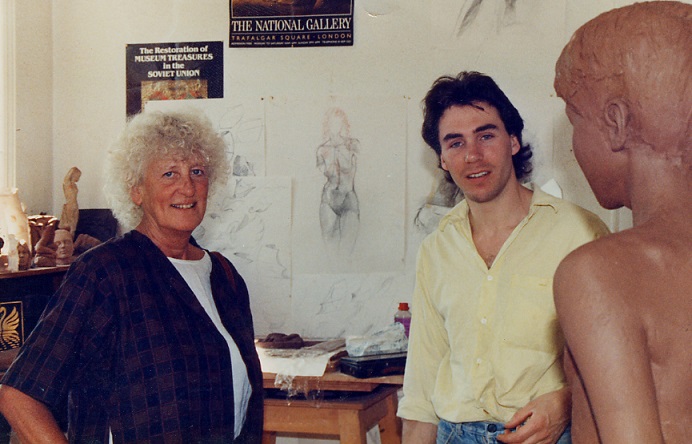

Dame Elisabeth Frink

And what of the artist? Frink was raised in Suffolk in a military family and World War Two broke out when she was a child, which had a major influence on her subsequent art. She studied at the Guildford and Chelsea Schools of Art and became part of a post-war group of British sculptors known as the ‘Geometry of Fear’ school. Their work was characterised by alien-looking metallic figures conjuring up a dystopian, blasted world which expressed societal anxieties in the immediate post-war years.

Dame Elisabeth Frink with John McKenna, a student at Sir Henry Doulton School of Sculpture, c.1987. (Creative Commons licence)

Frink’s subjects for her sculpture focused mainly on animals, especially horses, and the male figure. When asked why she didn’t use the female figure in her work, Frink responded, “ … I prefer the way they look. That doesn’t mean to say I don’t like women, but I don’t find female bodies at all satisfactory to sculpt.” (Interview by Brian Connell, Times Newspaper, 1977). She went on to explain that she found men’s heads and bodies a better vehicle for expressing a mood such as strength or sadness.

Gogglehead side and back views

Frink started to use the male head as a favourite form in the 1960s, beginning with soldiers’ heads as a political anti-war statement. She moved to the South of France in 1967 and began work on several series of ‘goggle heads’. She is recorded as saying that they were inspired by the Moroccan General Mohamed Oufkir, who habitually wore dark glasses, and she found not being able to see people’s eyes sinister. Our variant of Frink’s ‘goggle heads’ series looks bald but is actually wearing a type of close-fitting leather racing helmet and you can see the buckle on the side. He appears to have another strap, or possibly even a pigtail, at the back.

Does our Gogglehead have a sinister or sunny personality? Come and judge for yourself. You’ll find him waiting for you by the lift on our first-floor balcony.

To see some of Sal's conservation in action you can watch a short video on our YouTube channel.

Further information about Frink’s life and work:

https://artuk.org/discover/artists/frink-elisabeth-19301993

https://www.independent.co.uk/news/people/obituary-dame-elisabeth-frink-1456195.html

https://www.jennaburlingham.com/artists/30-elisabeth-frink/biography/

https://www.christies.com/features/Collecting-Guide-Elisabeth-Frink-9909-1.aspx

Frink’s last work ‘The Welcoming Christ’ is on the exterior of Liverpool’s Anglican Cathedral: https://www.geograph.org.uk/photo/4584725

Another Elisabeth Frink sculpture from the VG&M collection, Front Runner, is featuring in an exhibition at Messum’s Wiltshire 26 Sept 2021 – 16 Jan 2022: https://messumswiltshire.com/exhibitions/exhibition-elisabeth-frink-man-is-an-animal/

Keywords: Elisabeth Frink, Sculpture conservation, Sally Bowling Conservator , Bronze.