The Two Shipwrecks of the Circassian

Posted on: 29 July 2021 by Amanda Draper Curator of Art and Exhibitions in 2021

Hanging in our Nature v Humans exhibition is a painting of a dramatic shipwreck during a turbulent storm. The stricken Liverpool-bound vessel is called the Circassian and this is a fictional scene. However, forty years later, a real ship from Liverpool with the same name also foundered in an episode brimming with heroism and tragedy.

Title page of The Pirate by Captain Marryat, edition published by George Bell & Sons, London, 1882

The Pirate by Captain Marryat

Our story begins with ‘The Pirate’, a novel by Captain Frederick Marryat (1792 – 1848) who had a long career in the Royal Navy before resigning in 1830 to take up writing full-time. Unsurprisingly, the majority of his fiction was based on his maritime experiences although his most enduring work is ‘Children of the New Forest’. ‘The Pirate’, dating from 1836 but set in the 1790s, is one of Marryat’s earlier novels and is typical of his work with its tale of derring-do on the high seas. It must be admitted that the novel is out-dated in language and attitudes and Marryat’s portrayal of its African characters is unacceptable today. Let us concentrate instead on an illustration in the book.

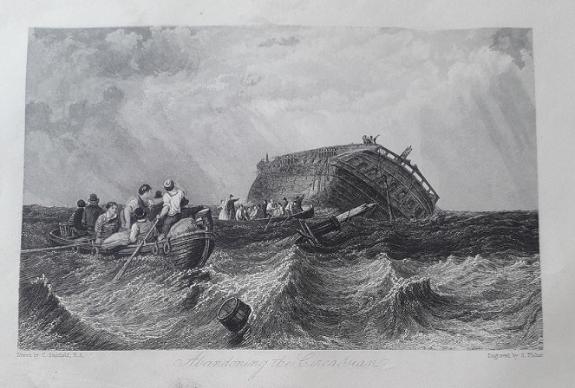

Abandoning the Circassian book illustration from ‘The Pirate’ (engraving by S. Fisher after the painting by Clarkson Stanfield)

Abandoning the Circassian

In ‘The Pirate’, the Circassian is a cargo vessel leaving New York and heading for Liverpool loaded with raw cotton and carrying a few passengers. The ship is driven into the Bay of Biscay by a three-day gale and a storm was brewing in this notorious graveyard for ships off the northern Spanish coast. The crew are forced to cut down the masts to prevent the vessel overturning but then the hull springs a leak and the ship quickly takes on water. It is decided to launch the two remaining seaworthy boats which had the capacity for all the crew and passengers. This is the scene we see captured in the book illustration above which is an engraving after an original watercolour by the eminent maritime painter Clarkson Stanfield. It is one of twenty Stanfield created for the book.

Abandoning the Circassian by Clarkson Stanfield, 1835 (watercolour). Courtesy of The Atkinson, Southport.

Clarkson Frederick Stanfield RA RBA (1793 – 1876)

Stanfield was given his unusual first name by his father in honour of Thomas Clarkson, a slave trade abolitionist. Stanfield’s father, James Field Stanfield, had worked on a slave-trading ship out of Liverpool and was so appalled by what he saw that he abandoned sailing and became an ardent abolitionist. Despite his father’s experiences, Stanfield junior became a merchant seaman aged fifteen before being press-ganged into the Royal Navy, only to be injured in a fall from rigging aged twenty-one and discharged. He then returned to the merchant navy for a year’s trip to China and back. After this he turned to art as a way of making his living, having been tutored in it by his mother, Mary Hoad, an actress and artist. Initially he painted scenery backdrops for theatre sets, but eventually his love of the sea won out and he began to focus more on maritime paintings in oils and watercolours. Stanfield was quickly recognised for the quality of his work. He was one of the founders of the Royal Society of British Artists, becoming President in 1829, and was elected a Royal Academician in 1835. He was considered one of the finest maritime painters of his generation and considered second only to J.M.W. Turner in his skill of capturing atmospheric effects at sea.

Busy Shipping Lane off Liverpool by Clarkson Stanfield (oil on canvas) (©Historic Environment Scotland)

The real Circassian

As we know, the dramatic scenes that Clarkson Stanfield illustrated of the Circassian being shipwrecked were based on a work of fiction. But so often truth is stranger than fiction and in 1876, the year of Stanfield’s death, a real ship called the Circassian suffered a real shipwreck with a tragic outcome.

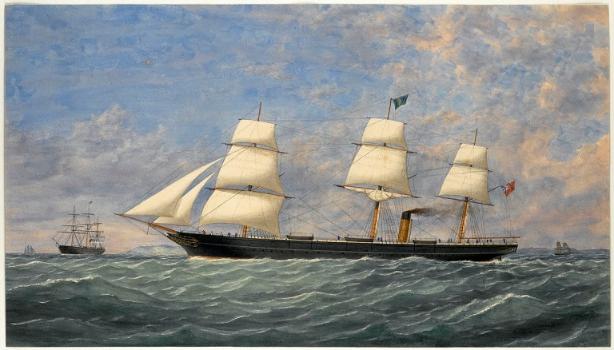

The Steam Ship Circassian, 1856 by unknown artist (watercolour) (© National Maritime Museum, Greenwich). Believed to be the ‘real’ Circassian.

This Circassian was an iron-hulled vessel sailing from its home port of Liverpool for New York laden with an industrial cargo which included bricks, chemical such as soda ash, 471 bales of old rags and 281 bags of hide pieces. She set sail on November 6th 1876. She had already had an eventful life, being built in 1856 as a steamer but the engine had been stripped out and she was now used full sail. Over the years she had been a passenger and cargo ship working the Irish Sea, then a blockade-runner during the American Civil War, then captured and used as a Union troop ship and by this time was owned by DeWolfe and Co. of Liverpool as a cargo workhorse. Onboard there was a crew of 35 plus one stowaway called John McDermott. The weather was heavy-going and there were numerous storms during the voyage. At one point the ship needed to rescue the stranded crew of a smaller vessel called the Heath Park. Continuing towards New York, on December 11th the ship ran aground off the treacherous Long Island shore. A rescue was launched by the local Life Saving Service, especially from the Mecox Station, and eventually all aboard the Circassian were delivered back to land safely.

![The last moments of the Circassian re-imagined [Internet sourced image]](https://vgm.liverpool.ac.uk/media/livacuk/victoriagalleryandmuseum/blog/7-1-558x329.jpg)

The last moments of the Circassian re-imagined [Internet sourced image]

However, insurance companies began to make plans to salvage the cargo and release the ship by using a wrecking crew if necessary. The Circassian’s captain insisted that his men would assist with salvage operations but not all were keen after what they had gone through and over half left for New York. He was left with fourteen crew plus the stowaway. The remaining Circassian crew and the wrecking crew reached out to the local Shinnecock Native American community for assistance as they had a reputation for volunteering in similar situations in the past. By 24th December a third of the cargo had been removed but on 29th December a greater storm rolled in. All the men helping with salvage were ordered to stay on board; it is rumoured at gunpoint. The force of the storm created a breach in the hull and the ship began to take on water. The crew sent up a distress signal and the Life Saving Service from Mecox Station again responded. It was the worst storm in living memory and the rescuers could not get near the ship. The Circassian began to break up and disintegrated around 4.30am on December 30th. There were only four survivors: three from the Circassian’s original crew and one of the wrecking crew. Twenty-eight had perished including all ten Shinnecock volunteers. It is still remembered as a great tragedy of the Long Island coast.

What is a Circassian?

To conclude, it should be explained who the two ships were named after. The Circassians, also known as the Adyghe people, are an ethnic group originating from the North Caucasus region. The traditional capital of Circassia is the city of Sochi. A bitter war with Russia lasting from 1763 to 1864, in which they were eventually defeated, left most of the population either dead or exiled from their homeland.

You can see the original painting of ‘Abandoning the Circassian’ by Clarkson Stanfield in our exhibition Nature v Humans which runs until the end of September 2021. We are indebted to The Atkinson, Southport for the generous loan of the painting.

Further information:

A full and highly informative account of the real Circassian’s shipwreck can be read here:

https://thehamptons.com/indians/shipwreck/intro.html

More paintings by Clarkson Stanfield in public collections can be seen on the Art UK website:

https://artuk.org/discover/artists/stanfield-clarkson-frederick-17931867-4592

NOTES:

1. The University of Liverpool was founded in 1881. We are aware that, as a civic institution created in one of the centres of Britain’s eighteenth and nineteenth century economy, and a seaport, the legacies of slavery and colonialism form part of our story. We are undertaking a period of reflection through which we will consider, in consultation with our members and local communities, how we might appropriately recognise this.

Keywords: Circassian, Clarkson Stanfield , Captain Marryat, Shinnecock, Shipwreck.