Faience and Fiascos

Posted on: 12 November 2021 by Kim Fisher, VG&M Visitor Services in 2021

In our previous Victoria Building History blog we learnt more about the original college building which had opened in 1882 and was based in the old asylum building on Ashton Street.

The college rapidly grew and it was not long before the inadequacies of the building became apparent and so in 1887, the year of Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee, the College launched a fundraising appeal for the erection of a purpose-built headquarters. The College’s Council asked Liverpool-born architect Alfred Waterhouse to draw up plans and in this blog we take a close look at the construction of the Victoria Building.

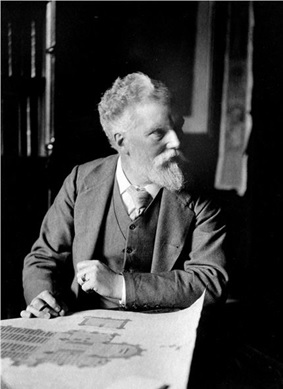

The architect: Alfred Waterhouse

Photograph of Architect Alfred Waterhouse

Alfred Waterhouse was one of the 19th century’s richest and busiest architects and he had an established reputation for college and university architecture. His portfolio included buildings for Oxford and Cambridge universities as well as numerous buildings in Liverpool and Cheshire and he had already completed Manchester Town Hall by 1877 and the iconic Natural History Museum in London by 1881.

He had also done some work for some of the college benefactors and Hinderton Hall on the Wirral is one such example. Christopher Bushell was much involved in the beginnings of University College Liverpool and helped to find a suitable site and appoint the first principal. In 1881 he joined the College Council and was the first Vice-President of the College and so he had personal experience of Waterhouse's work when his home was built in 1856. It was one of Waterhouse’s very early works when he was just 26 years old.

Christopher Bushell’s home Hinderton Hall was designed by Waterhouse. Photograph courtesy of Hinderton Hall Estate.

The budget for the Victoria Building was initially £35,000 and by November 1889 the College Committee had raised £38,000 thanks to the generosity of approximately 730 donors and work could now begin on the Victoria Building.

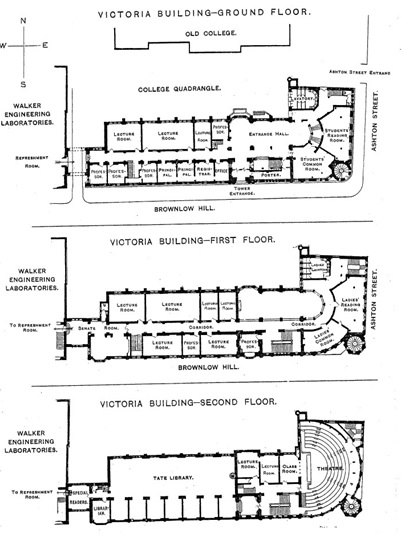

The Plans

One of the original ideas for how the Victoria Building might have looked without its clock, from University of Liverpool Special Collections & Archives.

Interestingly one of the first plans was to house facilities for the male students in the brand-new building and the women would stay in the old asylum building with a covered walkway linking the two. This plan was quickly abandoned and sanitary provisions were made in the new building for both sexes so that everyone could benefit from a new college building. Although the communal spaces were separates for each of the sexes, both the female and male common room and reading rooms were of equal size even though there were far fewer female students at the time.

The ground floor rooms were to be used for teaching Maths, German and Latin and the first floor rooms were used for teaching Greek, History, Philosophy, Italian, French and Modern Literature. Other subjects such as physics, botany and biology were still taught in the old asylum building and engineering was taught in the Walker Engineering Laboratory until more departmental buildings were constructed in the quadrangle over the next 20 years. On the second floor, English and Economic Science were taught.

Building plans for the Victoria Building from University of Liverpool Special Collections and Archives.

Correspondence, Collaborations & Construction

Correspondence between Principal Rendall and Waterhouse spanned from 1889-1896 and it is clear that construction did not run smoothly throughout the entire project and even after the building opened there were issues that needed to be addressed. On 18 December 1889 Rendall documented that work was going very slowly and that the terracotta was deficient, the iron girders were wanting, frost and wet weather also slowed progress and finally Henshaw subcontractors did not send the bricklayers.

It appears Principal Rendall did have quite a lot of input into the new College building design and we know that in his own rooms on the ground floor, he chose the inscriptions above his office fireplaces and paid for them himself.

The first fireplace inscription was written in Greek and translates as: ‘It is the function of a king to do good and be slandered for it.’ As the college principal Rendall undoubtedly tried to do his best but was probably slandered for some of his actions and so perhaps this was a personal motto and reminder that as a principal no matter how good your intentions, there will always be criticism but you must accept it and keep on going. In his other office, the quote ‘To Rule is to serve’ was the Latin inscription chosen above another fireplace and once again was a gentle reminder that as Principal of the college, his main job was to serve the wishes of the college.

One of the VG&M office fireplaces with the Latin Inscription ‘To Rule is to serve’ and a photograph of Principal Rendall.

The building had the benefit of over 40 years of collaboration between Waterhouse and firms that he trusted from all over the country. The foundations were laid by Isaac Dilworth of Wavertree, the building superstructure was carried out by Brown and Backhouse who were a local firm based on Chatham street and the brickwork was contracted to Joshua Henshaw and Sons who were also from Liverpool which shows that Waterhouse also liked to employ local tradesmen as well.

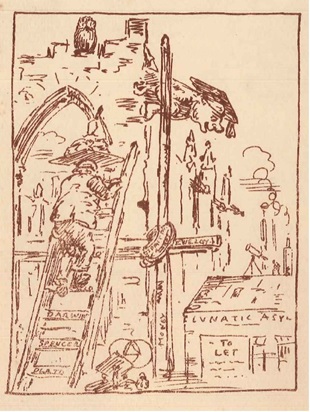

This sketch from the University of Liverpool’s Special Collections & Archives shows the construction of the Victoria Building overlooking the asylum. The sketch playfully depicts a man wearing a mortarboard next to a builder wearing mortar on a board on his head.

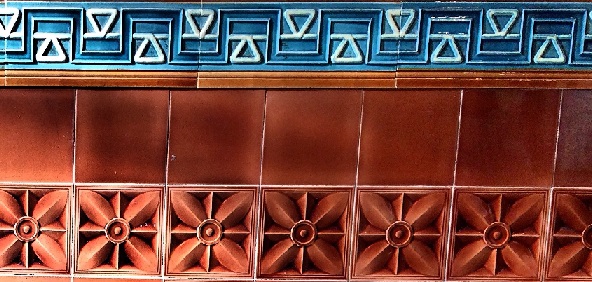

The faience and tiles were produced by Burmantofts of Leeds, the company was founded in 1845 and closed in 1957. The college committee had at first declined Waterhouse’s designs for a fully tiled building as the cost was significantly higher than the initial budget, but Waterhouse was insistent and the total cost for the faience and mosaics came to around £7,720 which would be considerably more if a similar building was constructed today.

The mosaic flooring was produced by Jesse Rust, who came to Waterhouse’s attention in the 1860s. He was a glass maker and manufacturing chemist which meant that he could turn old glass into cheaper and more durable material and his work can be seen in buildings like the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. Rust elaborated on how he made his mosaics by stating:

“I take old glass of any description and fuse it with a large quantity of sand together with the colouring matter. I thereby get a material resembling marble, but which is much harder and will resist moisture. Any colour and shape can be made in a fused state. I then press it into moulds, in the shape required either for geometric designs, or in squares to be broken up for mosaic.”

Mosaic floors in the Victoria Building

Benevolent Benefactors

The tower clock was made by Leeds clockmakers William Potts & Sons and cost around £629 and the bells and the bells were cast by Taylors of Loughborough which cost around £357 and they were gifted by William Hartley the jam manufacturer. In a clock tower opening ceremony at the Victoria Building on 15 November 1892, Hartley expressed the hope that the clock would be for the benefit of everyone connected to the university and to the citizens of Liverpool for generations to come. To this day, we hear of many stories of local residents who have used our clock and its bells as their own personal alarm clock and so Hartley’s wishes were granted as the citizens of Liverpool still cherish the clock tower today.

Another benefactor for the Victoria Building was Henry Tate, the sugar refiner of Liverpool and London who offered to fund the entire library block, amounting to £20,000. He donated a further £5,000 for books and £4,000 for the oak floorings and fittings in the Tate Hall. His initials can still be seen today on the celling corbels in the old Senate Room and his family crest is displayed on the end of the beams in the Tate Hall Museum.

The clock & bells mechanism commemoration plaque & the Henry Tate plaque.

Faience and Fiascos

At a college committee meeting in October 1891, it was indicated that the building would be ready for opening around Easter 1892 and plans were put in hand for the opening ceremony and the Prince of Wales was invited. However early in the New Year it became clear that the building would not be ready in time for Easter and the invitation to the Prince of Wales had to be withdrawn to which Principal Rendall wrote “I shrink from the risk of the fiasco involved.”

In May, it was known that the faience contractor could not finish before August and by September 8 1892 the staircase faience had still not been completed. From October 3 Rendall had to forbid workmen to enter the building between the hours of 9.30am – 1.30pm because although the building was not complete, the college had been forced to occupy the new building as the old asylum was being used by other departments and the faculty of arts had nowhere else to go.

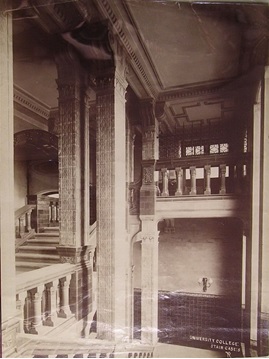

Second floor staircase faience shortly after completion in 1892.

As the go-between for the architect and the college committee, it is no wonder that Rendall chose the two inscriptions for his fireplace as increasing costs and late opening for the Victoria Building would have no doubt caused a lot of criticism but ultimately it was for the good of the College that Rendall and Waterhouse would work closely on designs and try to work out these problems.

The building finally opened on the 13th December 1892 and even at this point it hadn’t been completely finished. In his own section of the 1893 council report, Principal Rendall stated “The completion of the Victoria Building has completely changed the working conditions of student life”.

The final calculation for the building was £53,766 almost £19,000 over the initial budget and the college was in debt by £5000. But to put it into context, the renovations for the 2008 opening for the VG&M cost £8.6 million and so we can only imagine how much a building like this would cost today and so we are very lucky that we have such a wonderful building in the heart of our University campus.

Keywords: Alfred Waterhouse, University College Liverpool, Gerald Henry Rendall, Victoria Building, Burmantofts, Henry Tate, William Hartley, Hinderton Hall.