From Asylum to Academia

Posted on: 17 September 2021 by Kim Fisher, Visitor Services Team in 2021

If you stand behind the Victoria Gallery & Museum in the university quadrangle you may not realise that the foundations of the first building on this site lie beneath your feet. An asylum was erected here in 1829 and served until 1881 where it was repurposed and converted for the use of University College Liverpool. In this blog post we take a closer look at this buildings history.

Asylum accounts

From an early account of life in the asylum we know that bedroom doors were unlocked at 6.00 am and patients were washed and the state of their skin examined. At 9.00am, following breakfast, they were taken to the airing courts and gardens while the wards were cleaned. Bedtime was at 8.00pm, and patients slept in long rows of beds that were two feet and six inches apart.

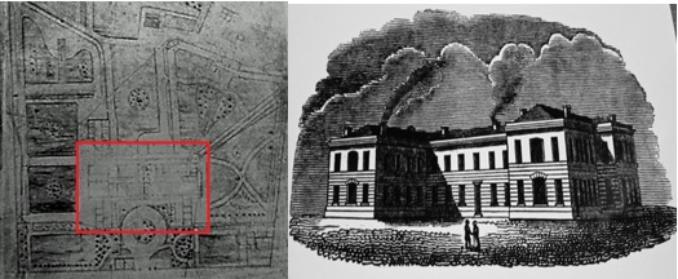

Although faded, this plan on the left shows the asylum building highlighted in red, surrounded by the airing courts and gardens. The image on the right shows a sketch of the asylum (University of Liverpool Special Collections & Archives).

After a visit to the asylum on the 8th of December 1849, The Liverpool Journal published the following harrowing account:

“The asylum I also visited, four adult men in a room above and seven women are confined.

I was shown into the men's ward, a lobby, reminding me of the guardroom of an ancient fortress. The bedrooms are recessed into the walls, four patients were seated around blazing fire and three or four keepers scattered around the room.

I was shown one of the straightjackets used for restraint. They are made of strong canvas and constructed so as the patient has to fold their arms, the sleeves are then tied behind their backs. On some inmates these jackets are forced every night and for further security the ankles are tied to the bed with leather straps.”

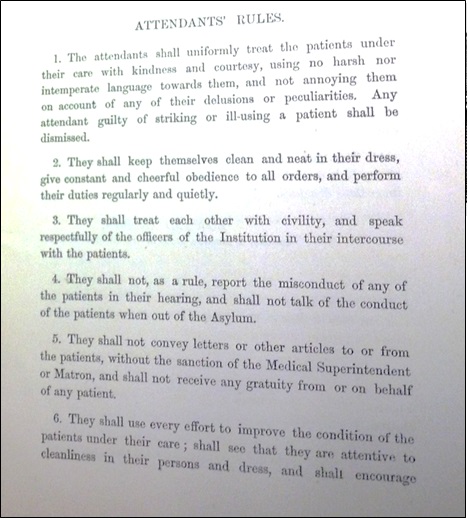

However, looking at the 1877 byelaws of the asylum it appears that the patients were to be well cared for and treated with respect which does contradict our modern view of the terrible conditions and treatment of patients in Victorian asylums.

From 'Laws and rules for the government of the Liverpool Royal Infirmary, Lunatic Asylum, Lock Hospital and the Liverpool Royal Infirmary School of Medicine', 1877, Liverpool Record Office.

Site for Sale

In 1881 the asylum and its grounds were sold to the London and North-Western Railway Company who intended to construct a new line from Edge Hill to Lime Street station. The new line passed right underneath the building which would have been distressing for the patients with all of the noise and smoke from the trains and so the asylum closed and the patients were moved to other local institutions like Rainhill.

Not all of the land was required by the railway company and in 1881 Thomas Cope, the founder of a Liverpool tobacco manufacturing company, bought the land for approximately £20,000 which he then presented to University College Liverpool as a loan. The Corporation of the City of Liverpool also applied to Parliament to raise £30,000 to secure the land and buildings on this site.

The college employed Alfred Waterhouse, who had extensive experience designing academic institutions in Oxford and Cambridge, to draw up plans to renovate the old asylum.

The conversion cost £20,000 and on the 14th January 1882, the college opened with 45 students.

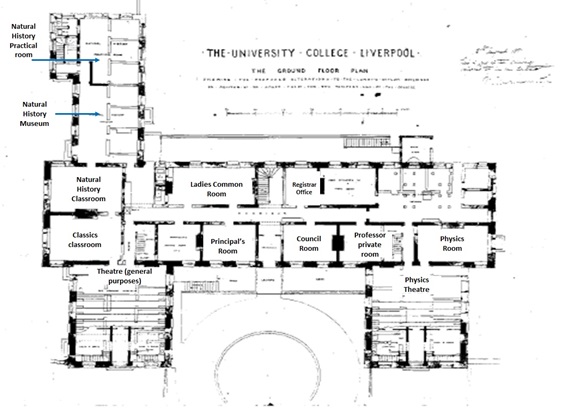

Waterhouse’s converted asylum plan for the ground floor shows how University College Liverpool would use the old building. (University of Liverpool Special Collections & Archives).

The adapted asylum and University College Liverpool

The converted building served to accommodate Natural History, Physics, Engineering, Architecture, Modern Literature and Law, together with a lecture room, library, reading room, ladies' common room and professors' common room.

One story attached to the building is of a professor who was working late one night and found himself locked in the deserted building. He attracted the attention of a passing policeman from an upper window and said he had been locked in by mistake. To which the policeman replied "Ah! They all say that." But there is no mention if the professor was ever let out!

Physics Professor Oliver Lodge was one of the first to move in to the renovated asylum building and stated the following:

‘The asylum didn't look at all promising as a college. It was still in the hands of workmen who were taking out partition walls in the interior and converting each of the two wings containing two dozen or so small bedrooms on two floors into a good-sized lecture theatre. The padded room had not been pulled down when I went there but it disappeared along with the rest and became part of my laboratory.

There is nothing sacred about the walls that are left, they can be plugged and pulled about and holes cut in them where ever wanted. By ingenious scheming, fittings can be adapted to the circumstances and where these are successful you can be pleased accordingly, while if you are unsuccessful you have nothing to blame yourself for.’

Left – Professor Oliver Lodge (physics), Right – Principal Gerald Rendall (University of Liverpool Special Collections & Archives).

As student numbers increased it became clear that the renovated asylum was not adequate and Principal Rendall’s Annual Report of 1887 drew attention to the fact that a new building must be erected:

‘Every fragment of space, corridor or closet, heated or unheated has been pressured into service: single rooms are curtained off into double, no professor or lecturer can regard any lecture room as his own and equip it accordingly: maps and diagrams must be carried from room to room: successive classes must wait on one another’s exit and use the air exhausted by predecessors. There is no common room for members of staff…every professor's private room is shared between two or more…Library books are stowed away in cupboards because there is no room for new shelves…Student common rooms and meagre luncheon rooms are in the basement…there is no lecture room capable of accommodating an attendance of 150 and college functions must be enacted anywhere but in the college.’

Other accounts from students recalled how dreary the old building was:

'Men students had a cellar in the old building as a common room; it is not easy to imagine a drearier place and it was never exactly crowded. The cellars of the old building also contained a refectory where we chiefly consumed mutton pies and poached eggs.'

After fundraising began in 1887 for a new building, the Victoria Building’s construction finally began in 1889 and the building opened in 1892.

A sketch showing the construction of the Victoria Building and the old asylum building with a ‘To Let’ sign in the window. (University of Liverpool Special Collections & Archives).

Even after the Victoria Building was opened, the college still used the old asylum building for teaching. Mrs Edna Rideout wrote about classes in the old asylum and details the account of a humorous folk dance that brought the house down:

"During the session 1913-1914 I read a course in Economics. Lectures were given by Mr Macdonald in a room on the first floor of this old building. The room was heated by an open coal fire which Mr Macdonald kept generously stoked from a well-filled open scuttle. The room was dusty and had a peculiar smell, compounded I suppose by rotting timbers and dirt. Mr Cecil Sharpe collector of folk songs and pioneer of folk dancing gave a lecture to the students. He was allotted a first floor room in the asylum. Fired by his enthusiasm some of us announced our intention of starting a Folk Dance Society. He responded by teaching us on the spot the dance 'Gathering Peascods.' This energetic dance proved to be too much for the old structure, and we literally went through the floor. I recall no repercussions from this damage to the fabric...."

The Victoria Building was completed in 1892 and served as the main hub for the university for a number of years with purpose-built classrooms, lecture theatres and adequate spaces for staff and students. Over the next 20 years, brand new buildings grew around the old asylum building but it was still used by various departments up until 1914 and then demolished not long after.

The only surviving photograph of the asylum around 1914 with demolition crew standing in the foreground. (University of Liverpool Special Collections & Archives).

Hidden History

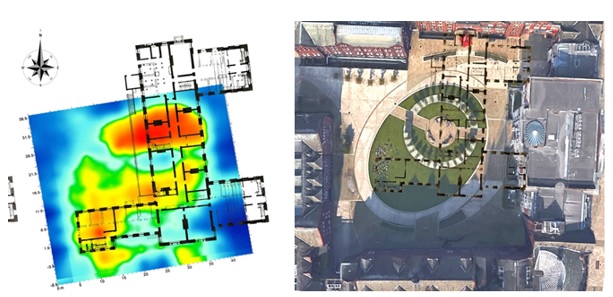

All that remains of the asylum is the shape of the current quadrangle which had grown up around the site and when the quadrangle was redeveloped in 2012 the original foundations could be seen under the ground. By looking at historic photographs of the site, ADP Architecture discovered that the quadrangle had originally had an oval shape and formed the basis of their designs for the Diamond Jubilee Quadrangle that we see today.

Diamond Jubilee Quadrangle construction around 2011 where evidence of the asylum foundations could be seen.

In 2017 a geophysical survey was completed by a student at the university. Simon Lloyd found that all of the foundations are still intact beneath the grassed area in the centre of the quad and match the plans drawn by Waterhouse.

Simon Lloyds 2017 geophysical survey of the area and how it fits in to the current oval design of the jubilee quadrangle.

Today the quadrangle is enjoyed by staff, students and public alike in the current landscaped garden and although there is no physical marker to commemorate the men and women who lived in the asylum and its airing gardens, we hope that this blog has highlighted a part of Liverpool’s hidden history.

Keywords: Victorian Asylum, University College Liverpool, Alfred Waterhouse, University of Liverpool History, Quadrangle, Geophysical Survey, Liverpool Hidden History.