The Tale of the Nightmare Boss

Posted on: 27 May 2021 by Amanda Draper Curator of Art and Exhibitions in 2021

Ever had a boss who makes you do all the work while they sit back and do nothing? It’s not a modern phenomenon. Meet Moses, the beleaguered underling of this lazy and drunken Vicar, humorously immortalised in 18th century pottery and prints.

The Vicar and Moses glazed pottery figure group c.1790 by Ralph Wood (VG&M collection)

What’s the Story?

Two figures sit in a church pulpit; the Vicar, who should be preaching to his congregation, is fast asleep, leaving his assistant to present the sermon for him. This morality tale in miniature measures just under 25cm high.

The Vicar and Moses was made around 1790 during what is considered the ‘golden age’ of satire in Georgian Britain, expressed through visual means but also in literature, plays and song. The focus for satirists could be famous figures from royalty, high society and politics but there was also scorn for professions such as doctors, lawyers and, of course, the clergy, who were often perceived as under-worked and overpaid.

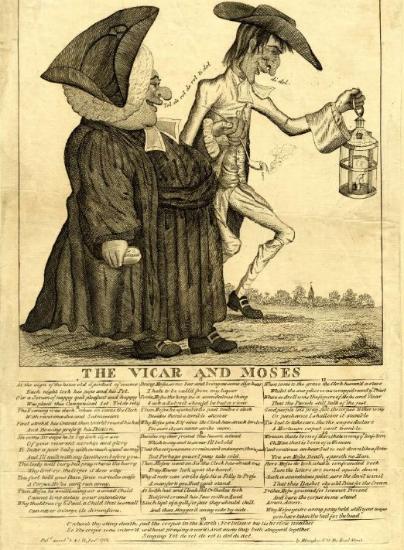

The Vicar and Moses broadsheet, 1782 attributed to Thomas Colley (©The Trustees of the British Museum)

Origins of the Vicar and Moses

It is not entirely clear where the tale of the Vicar and Moses originated, but a song with that title was published in 1773 by Charles and Samuel Thomson of London. There are at least two versions of the song. The earliest known visual representation of the Vicar and Moses (shown above) was published by the renowned London print shop owner Hannah Humphrey in 1782 using a drawing attributed to Thomas Colley. The song lyrics that accompany this print are the harsher of the two versions. It tells of a funeral party waiting at the church where a child is to be buried, but the vicar is at a nearby inn drinking. His clerk, Moses, goes to fetch him but is persuaded to stay and drink himself. By the time the pair leave for the church both are very inebriated, neither can read the burial service and they are as bad as each other.

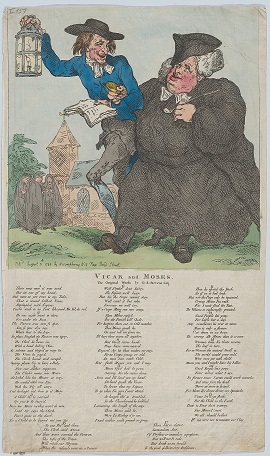

The Vicar and Moses, 1784 by Thomas Rowlandson (Collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Creative Commons licence)

A couple of years later Hannah Humphrey published a second Vicar and Moses print, but this time using words credited to George Alexander Stevens (1710 – 1780), a London-based performer and comic songwriter. His lyrics appear in book called ‘Songs, Comic and Satyrical’ first published around 1780 (see link below). In Stevens’ version, Moses persuades the Vicar to leave the pub immediately but he is still too drunk to read the burial service for the child, so Moses does it for him. This make Moses the hero and gives a satisfactory closure, of sorts, to the tale. It appears to have been the more popular version of the song.

The artist Thomas Rowlandson was one of the leading caricaturists and satirists of his day. He follows several of the visual references used by Colley. The Vicar is extremely corpulent with thick grey hair which is probably a wig. Moses, in comedic comparison, is extremely thin and ‘lights the way’ which may be an allusion to his moral influence. In both, the Vicar clutches his tobacco pouch and has a white clay pipe; just another of his many vices. The sad funeral party waiting by the church can be seen on the left. Although perhaps too dark a tale for us to find amusing now, the Vicar and Moses was incredibly popular in its day. The story then took on a life of its own with the Vicar and Moses featuring in scenarios not mentioned in the original song.

The Further Adventures of the Vicar and Moses

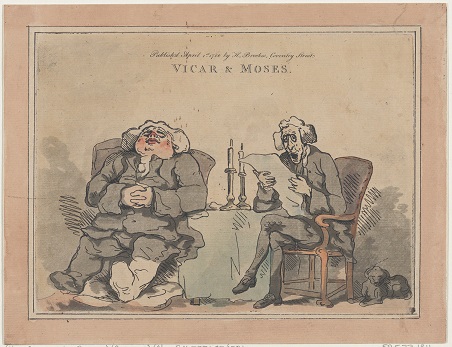

Vicar and Moses, 1786 by Thomas Rowlandson (Collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Creative Commons license.)

We begin to see a back-story to the relationship and life of the Vicar and Moses. In the above print by Thomas Rowlandson from 1786, an older and more respectable-looking Moses reads to the dozing Vicar. Although no alcohol is evident, the Vicar is resting his left foot in an attitude typical of a gout sufferer; a painful medical condition historically associated with over-indulgence of rich food and drink. Alongside Moses’ chair lies a docile dog, a symbol of faithfulness and companionship.

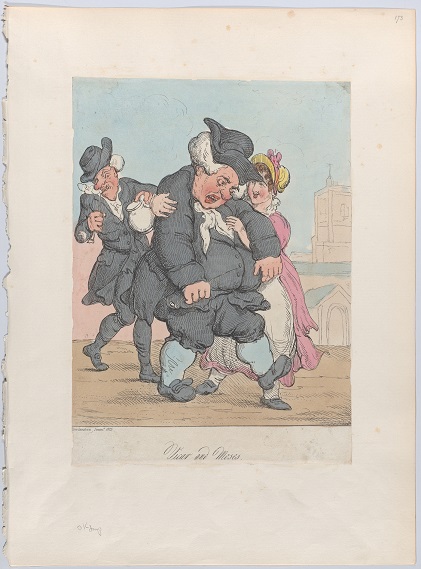

Vicar and Moses, 1815 by Thomas Rowlandson (Collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Creative Commons license)

But we would be disappointed if the Vicar did not break out with another episode of louche behaviour. In a much later rendering of the tale by Thomas Rowlandson from 1815, the Vicar is being propped up by a young lady who seems to have designs on his person, maybe even matrimony. Moses follows behind with a jug, presumably of ale, to keep the Vicar topped up.

The Vicar and Moses in pottery

The Vicar and Moses in lead-glazed earthenware, c.1800 by Enoch Wood (©Victoria & Albert Museum, London)

By the late 1780s the Vicar and Moses were also being depicted in ceramics. The Victoria & Albert Museum have a version showing the two figures in the same pose as the earlier prints, with Moses trying to lead an obviously tipsy Vicar while holding a lamp. You could even get this scene printed on a mug (see Winterthur Museum link below).

The Vicar and Moses front and back view (VG&M Collection)

Ralph Wood II (1748 – 1795)

It is believed that the VG&M’s Vicar and Moses was made by the workshop of Ralph Wood Jr around 1785 – 90. He was a member of a celebrated dynasty of potters based in Burslem in Staffordshire who specialised in finely modelled figures and character vessels like Toby jugs. A younger member of the family, Enoch Wood, created the V&A Museum’s ceramic figures seen previously. There is a suggestion that the modeller of the figures was an employee called John Voyez, a talented but rather wayward Frenchman who had previously been fired from Wedgwood for improper behaviour. His faces are known for being rounded with the slightly flattened, bulbous noses seen here. This figure group is a ‘flatback’, designed with all the modelling facing forward and a smooth, straight back. It would typically be displayed on a mantlepiece or shelf with the back against a wall.

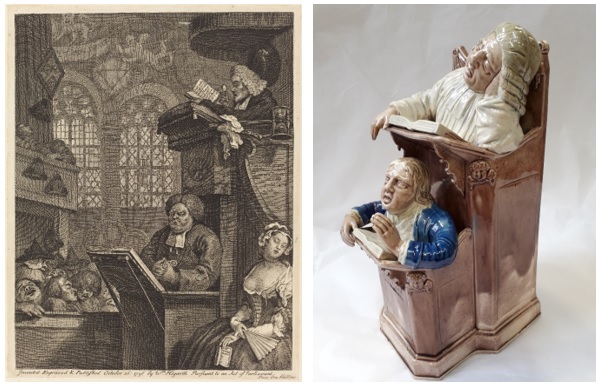

Left: The Sleeping Congregation, 1736 by William Hogarth (Collection of the National Gallery of Art, Washington; Creative Commons license).

The VG&M’s Vicar and Moses ceramic shows the pair seated in a two-tiered pulpit; an idea that Ralph Wood seems to have originated but was later much copied. The inspiration for its pulpit design is likely to have come from this famous etching by William Hogarth (above left), probably Britain’s greatest satirist in visual art. Dating from 1736, The Sleeping Congregation shows two clerics in a ‘double-decker’ style pulpit. At the top, the vicar is boring his congregation to sleep with the monotony of his sermon. Underneath, his lecherous assistant leers at the exposed cleavage of a snoozing woman.

Wood’s choice of the ‘double-decker’ pulpit allows for a visual joke whereby Moses appears oblivious to his sleeping boss. It is a sophisticated idea that reinforces the earnest goodness of Moses juxtaposed with the lazy, debauched Vicar set out in Stevens’ version of the song. And, because it must be set inside a church where they are working, it gives the viewer yet another episode in the life of this odd but enduring double act.

Further information

George Alexander Stevens: The Vicar and Moses, from Songs, Comics and Satyrical:

More detail about prints and ceramics mentioned above:

Information on Staffordshire figures:

Keywords: Vicar and Moses, Ralph Wood, Thomas Rowlandson, Thomas Colley, William Hogarth, George Alexander Stevens, Hannah Humphrey.