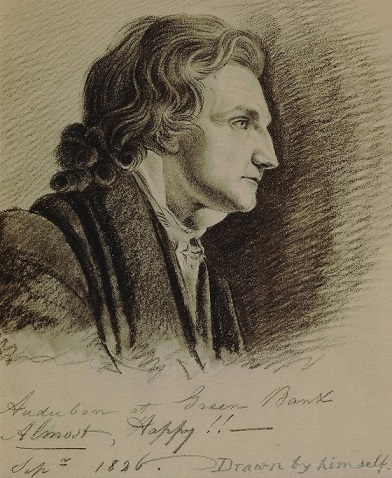

John James Audubon (1785-1851)

Posted on: 29 January 2021 by Leonie Sedman, Curator of Heritage & Collections Care in 2021

The 27th January 2021 will mark the 170th anniversary of the death of the American naturalist and artist John James Audubon, the author/creator of what is now one of the most valuable printed books in the world. Only 120 complete copies are known to have survived, but one of them is on display at Liverpool Central Library.

Here at the Victoria Gallery & Museum we are fortunate to be the custodians of the largest group of original artworks by Audubon outside North America. So how did these rare artworks end up in the collection of the

University of Liverpool?

His mission was to raise money for the publication of The Birds of America his monumental work, which would eventually consist of 435 hand-coloured, life-size prints of 497 bird species. He had already spent a number of years exploring the American wilderness and painting every species of bird that he could find. He had developed his own unique method of shooting a bird with a small shot so as not to damage it too badly, then using a wire armature to arrange the bird into a lifelike pose for him to paint.

Hawk Pouncing on Partridges, 1827

Hawk Pouncing on Partridges, 1827Liverpool society found the colourful and eccentric ‘American Woodsman’ Audubon fascinating, and in turn, he became very friendly with the Rathbone family. His journals describe just how much he admired them, and loved staying at Greenbank House. Before becoming a house guest, he more than once walked from his hotel in the city centre to Greenbank to find them not at home, so walked back to the city again.

A letter from Mrs Rathbone to her son Theodore in August 1826 reads:

Sept 1826

An Otter Caught in a Trap, 1826

It was thanks to Mrs Rathbone that the little robin seen in the watercolour above, was painted from life, and not with the help of a wire armature. The robin used to visit her in her study and she entreated Audubon not to kill it.

William Rathbone encouraged Audubon to paint a series of oil paintings to demonstrate his skill as an artist – and to exhibit them at the Liverpool Royal Institution as a way of drawing attention to his work and gaining subscribers.

The Liverpool Royal Institution had been founded in 1814 by a group of Liverpool merchants and professional men, associates of the Liverpool philanthropist William Roscoe (1753 – 1831). Roscoe and his like-minded circle founded the town’s Athenaeum, Literary and Philosophical Society, Lyceum, Liverpool Academy and Botanic Garden, bringing a new cultural impetus to late 18th-century Liverpool. The plan provided for a School, Public Lectures, accommodation for Societies, Collections of Books, Art, and Natural History, a Laboratory, and meeting rooms for the Proprietors, its financial backers. The lecture programme included anatomy, physiology, chemistry, botany, zoology, history, philosophy, political economy, geology, astronomy, literature, music and fine art, and created the foundation that would later become the University of Liverpool. The collections that originated there are now in the care of National Museums Liverpool, the Central Library and the University of Liverpool Victoria Gallery and Museum.

William Roscoe was the Chairman of the Institution’s General Committee in 1814, and its first President in 1822. A lawyer by profession, he was a historian, art and book collector, botanist, poet and politician. His deputy was John Gladstone (father of the later Prime Minister). John Gladstone was the head of one of the largest slave-holding families in the world (he received the largest compensation in the city after slavery was abolished). Roscoe and the Rathbones were all fiercely abolitionist. It is interesting to ponder whether this might have been where the future Prime Minister William Gladstone was swayed to support the abolitionist cause. Interestingly, being on different sides of the abolitionist debate didn’t seem to prevent the members of the Institution from collaborating and working together. It was into this environment that Audubon was introduced.

Christoph Irmscher: https://publicdomainreview.org/essay/audubons-haiti

Keywords: John James Audubon, Museum, Gallery, Birds of America.