The Bidston Hill Signals Mug: A Who's Who of the Liverpool Slave Trade

Posted on: 26 November 2021 by By Andrew Williams, Collections Assistant in 2021

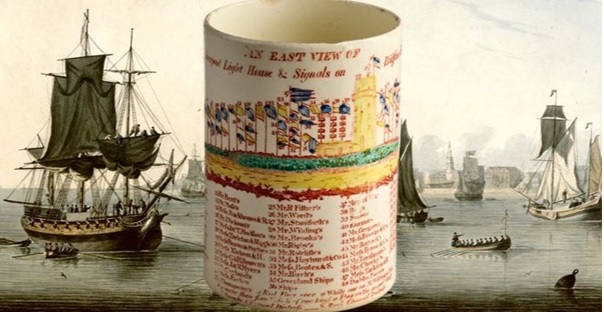

Sometimes, otherwise unassuming objects in the Victoria Gallery & Museum can give a remarkable insight into an abominable and infamous past. One such object is the Bidston Hill signals creamware mug, currently on display in Gallery 1, which unlocks a glimpse at an important period in Liverpool’s maritime history: when the Transatlantic Slave Trade was thriving.

Bidston Hill lighthouse, atop one of the highest points on the Wirral, was in operation from 1771 until 1913 (it was rebuilt in 1873 and this second lighthouse building survives to this day). The lighthouse guided ships into the Mersey, while the purpose of the signals was to alert workers at the docks to the arrival of ships belonging to certain merchants. The process of erecting a new signal in the early nineteenth century was described by Philip Barrington Ainslie in his Reminisces of a Scottish Gentleman:

Soon after the commencement of my engagement with Messrs Addison and Bagot, Mr Addison proposed that I should accompany him to Bidston Hill, for the purpose of arranging for a signal pole he wished to have erected there… I greatly enjoyed the fine and extensive view from the hill, and, after Mr Addison had arranged with the keeper of the signal-poles as to a position for that for his firm, we retraced our steps and recrossed the Mersey from Birkenhead. As a fleet was hourly expected from Jamaica, I kept a bright look-out towards Bidston, and was much gratified when, at length, I discovered the colours run up by which Messrs Addison and Bagot’s signal was distinguished.

The signals, which were in use for about one hundred years, were a very popular symbol of Liverpool in the late Georgian and early Victorian period. Paper prints were made for visitors, and these were also printed onto creamware ceramics, such as mugs and jugs.

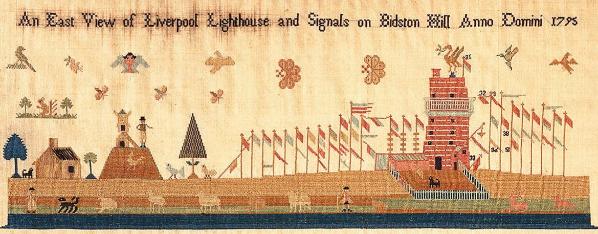

Extract from a needlework sampler by Elizabeth and Andrew Brunnell, depicting Bidston Hill in 1795. Courtesy of the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, New York City, public domain.

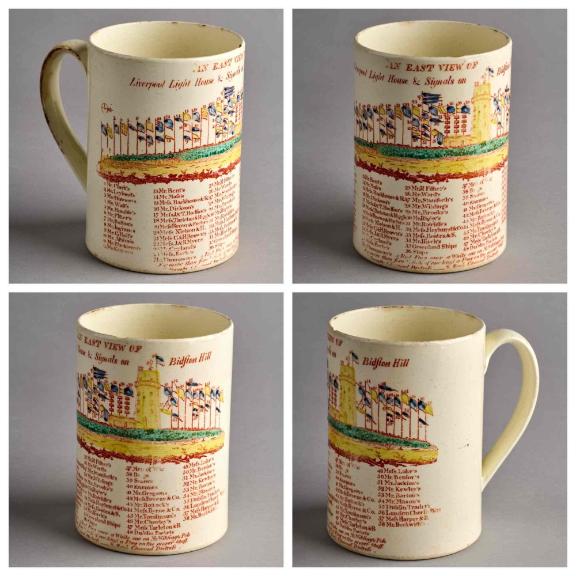

Our mug is not entirely unique: many similar ceramics exist in museums across the country, with a concentration in the collections of National Museums Liverpool. While some are dated, many are not, but the number of flags can give an indication of age: generally, the more flags, the more recent the print. The Victorian ceramic art historian Llewellyn Jewitt claimed that most of the Bidston Hill ceramics were made by Guy Green (1729–1804), a sometime business partner of John Sadler. Green was not necessarily the most impressive artist in Liverpool at the time, as Knowles Boney wrote in 1957: “We get the impression that Green was rather a colourless personality, always feeling inferior and behaving generally in the manner of the poor relation.” Unfortunately, there are no markings on the mug in our collection which indicate the artist or manufacturer.

In his 1795 history of Liverpool, James Wallace wrote: “There are at this time fifty-eight [signals], of which forty-nine belong to particular merchants, the remainder are to distinguish and shew if the vessels coming in are Greenlanders, men of war, or if the vessel is ship, brig, or snow; there are also immediate signals to the town of all vessels seen in distress in either of the channels, that thereby speedy assistance may be given.”

The figures given by Wallace correspond to the number of flags on the mug in our collection, which would date, at the very least, the print to 1795. However, in an edition of the volume two years later, Wallace gave the same number of flags, which suggests he was not using the most up to date information, in which case the figures in his 1795 edition may have been out of date, too. It is highly likely that the print comes after 1792, which was the outbreak of war with France, hence the inclusion of ‘Enemies’. If the Mr Bostock depicted on the mug is Robert Bostock, a major Liverpool slave trader, then it must date before his death at the end of 1793, placing the print in 1792 or 1793.

‘Bidston, Wirral, Old Lighthouse and Flagpoles’ by Robert W. Salmon (1775–1851), 1825. Courtesy of Merseyside Maritime Museum, Liverpool, licensed for reuse CC BY-NC.

It is not surprising that a depiction of the highest-volume maritime traders through the port of Liverpool in the early 1790s includes many who engaged in the slave trade. The Slave Voyages database includes records for 1,005 voyages that originated in Liverpool during the last decade of the eighteenth century, enslaving more than 285,000 Africans, or an average of 318 on each voyage. By cross-referencing the names on the mug with Craig and Jarvis’ Liverpool Registry of Merchant Ships and Gore’s Liverpool Directory, the identity of many of the merchants can be confirmed. Searching these names in the Slave Voyages and Legacies of British Slavery databases provides a picture of their business interests, and the extent to which they were involved in the slave trade, typically as the co-owner of a slave ship. Some on the list invested in over 100 voyages in their lifetimes.

Images of the mug in our collection. University of Liverpool Art Collections, CER.61.

To choose just one example, number two on the mug is Thomas Leyland. In 1776, he won £20,000 in a lottery and with the money set himself up in the business of enslavement. According to the Slave Voyages database, he had an interest in 72 slaving voyages out of Liverpool. He subsequently entered into banking, and set up Leyland & Bullin bank in 1806, which later merged into Midland Bank, and then HSBC. He was Lord Mayor of Liverpool three times and died in 1827 with a fortune of over £600,000, making him one of the richest men in England. Archival records about his career are held primarily in Liverpool Record Office, but some manuscripts about ships he co-owned can be viewed in Special Collections and Archives at the University of Liverpool Library [LUL MS 107/5].

As an aid to interested readers or future researchers, this blog post has been appended with a list of the merchants on the mug and their believed identity.

Further information

You can see the mug on display in our ceramics gallery. For details about visiting Victoria Gallery & Museum, see: https://vgm.liverpool.ac.uk/your-visit/.

Special Collections and Archives at the University of Liverpool Library holds a pamphlet with a key to the Bidston Hill signals, published circa 1820 [SPEC G35.19(11)]. To read a guest post about the pamphlet on their blog, Manuscripts and More, by Nicola Scott, Assistant Curator Decorative Art at National Museums Liverpool, see: https://manuscriptsandmore.liverpool.ac.uk/?p=2511.

Appendix

- Mr Clark’s: Thomas Clarke, slave trader, owned Kitty’s Amelia which performed the last legal slaving voyage by a British vessel

- Mr Leyland’s: Thomas Leyland (1752–1827), slave trader, three times mayor of Liverpool

- Mr Dawson’s: John Dawson (d. 1812), slave trader, in partnership with Peter Baker

- Mr Watt’s: Richard Watt I (1724–1796), slave trader, owner of Speke Hall

- Mr Humble’s: Michael Humble, ship builder

- Mr Fisher’s: John Fisher, slave trader

- Mr Bolton’s: John Bolton (1756–1837), slave trader and slave owner

- Mr Ingram’s: Francis Ingram (1739–1815), slave trader and privateer

- Mr G Hall’s: John Hall?

- Mr Ashton’s: Nicholas Ashton (1742–1833), salt and coal merchant exporting to America

- Mr Blackburn’s: John Blackburne (1754–1833), slave trader and MP for Lancashire, voted against abolition in 1807

- Mr Kenyon’s: James Kenyon, merchant and cotton importer

- Mr Bent’s: Robert Bent (1745–1832), slave trader and MP for Aylesbury

- Mr Moss’s: Thomas Moss (d. 1805), slave trader and timber merchant

- Messrs Backhouse & R: Backhouse and Rigg?

- Mr Dickson’s: William Dickson Sr (1740–1802), slave trader

- Messrs J & T Hodson’s: John Hodgson and Thomas Hodgson

- Messrs Tarleton & Rigg’s: Clayton Tarleton and William Rigg

- Messrs Brown & Forbes: William Forbes

- Messrs Nielson & H: William Neilson (1772–1857) and William Heathcote, slave traders

- Messrs G & H Brown’s: George Brown and Henry Brown, slave traders

- Messrs J & R Myers: John Myers and Robert Myers, merchants

- Mr Copland’s: John Copland (b. 1727), slave trader

- Messrs Earle’s: Thomas Earle (1757–1822), slave trader

- Mr R Fisher’s: Ralph Fisher (1746–1803), slave trader

- Mr Ward’s: Joseph Ward (d. 1832), slave trader and plantation owner

- Mr Staniforth’s: Thomas Staniforth (1735–1803), slave trader, mayor of Liverpool

- Mr Wilding’s: Richard Wilding (d. 1797), Bidston Hill lighthouse keeper

- Mr Brooks’s: Joseph Brooks (1746–1823), slave trader

- Mr Rigby’s: Thomas Rigby, slave trader and plantation owner

- Mr Ratcliffe’s: Jonathan Ratcliffe, slave trader

- Messrs Hayhurst & Co: Thomas Hayhurst (1762–1815), slave trader

- Messrs Boates & S: William Boats (1716–1794) and Thomas Seaman, slave traders

- Mr Birch’s: Joseph Birch (1755–1833), slave trader and MP for Nottingham

- Greenland Ships: These ships were involved in whaling

- Ships: This may have been a generic categorisation for all other ships

- Men of War: These would be Royal Navy warships

- Brigs: Fast and manoeuvrable ships with two square-rigged masts

- Snows: Similar to a brig, but with a snow mast immediately behind the main mast

- Enemies: Probably the French, due to the War of the First Coalition

- Mr Gregson’s: William Gregson Sr (1721–1800), slave trader, co-owner of the Zong

- Messrs Breeze & Co: Samuel Breeze, merchant

- Mr Bostock’s: Robert Bostock (1743–1793), slave trader

- Messrs Byrne & Co: John Byrne

- Mr Tomlinson’s: John Tomlinson, slave trader

- Mr Chorley’s: John Chorley, slave trader and plantation owner

- Messrs Tarleton & B: Thomas Tarleton (1753–1820), John Tarleton (1755–1841), and Daniel Backhouse (d. 1811), slave traders

- Dublin Packets: Cargo ships travelling between Liverpool and Dublin

- Messrs Lake’s: William Charles Lake, slave trader

- Mr Benson’s: Moses Benson (1738–1806), slave trader

- Mr Jackson’s: John Jackson, slave trader

- Mr Kewley’s: Patrick Kewley, slave trader

- Mr Barton’s: Thomas Barton, slave trader and plantation owner

- Mr Mason’s: Edward Mason, slave trader, partner of Cornelius Bourne

- Dublin Traders: Ships trading with Ireland

- London Cheese Ships: Ships transporting cheese exported from Liverpool to London

- Messrs Harper & B: William Harper (1749–1815) and Robert Brade (1747–1815), slave traders

- Mr Beckwith’s: William Beckwith, merchant

Keywords: Slave trade, Birkenhead, Ceramics, Maritime, Signals, Lighthouse, Mug.