Having cake, but not eating it

Posted on: 10 March 2021 by Amanda Draper, Curator of Art and Exhibitions in 2021

Tucked inside an ornate sewing box, carefully wrapped in tissue, is one of the oddest and most enigmatic items in our collection. It is a royal relic and the legacy of someone who had their cake, but didn’t eat it.

Mysterious object in an antique sewing box

A mysterious object

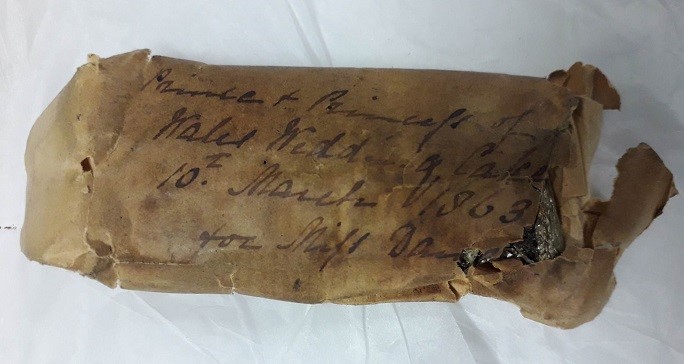

Carefully open the lid of the Georgian sewing box and, in the centre, you will see something wrapped in white acid-free tissue paper. Lift it out very slowly and gently, gently unfold the paper to reveal … something wizened and tubular that has a rip at one end. What on earth is it? It is a small piece of cake (fruit cake to be precise) wrapped in fragile brown paper with spidery handwriting from a bygone age telling us:

“Prince & Princess of Wales Wedding Cake 10th March 1863 for Miss Dar …”

Oh no! Just when we are about to find out who didn’t eat the cake, they rip the packet open across their name and now we may never know. Such are the conundrums that come with some museum objects.

“Prince & Princess of Wales Wedding Cake 10th March 1863 for Miss Dar …”

Oh no! Just when we are about to find out who didn’t eat the cake, they rip the packet open across their name and now we may never know. Such are the conundrums that come with some museum objects.

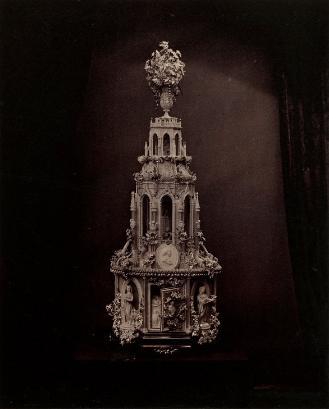

Royal Wedding Cake, 1863 (albumen print, courtesy of the Royal Collections Trust RCIN 2905626)

The Cake(s)

The small piece of cake probably comes from one of two made for the royal wedding between Edward, Prince of Wales and Princess Alexandra of Denmark held in St George’s Chapel, Windsor Castle. Five hundred people were invited to the wedding; there were two wedding ‘breakfasts’ and so two cakes were made. One was made by Messrs Bolland of Chester, a Royal confectioner, and stood five feet high. The other, illustrated above, is understood to have been made by the Queen’s confectioner Monsieur Pagniez, housed in a towering gothic edifice decorated with figures, insignia and jasmine flowers. We don’t know which cake our piece came from but, from peeking through the wrapper of our little slice, the cake had white icing of the hard type know as ‘royal’ with a silvered coating.

Cake housed in a gold-plated casket (By kind permission of Daniel Bexfield Antiques)

A Treasured Possession

Miss D must have treasured her cake so much as a memento of being part of a national day of celebration that she could not bring herself to eat it. Instead, she put it in her sewing box for safekeeping and it has been there ever since. It may well be one of only two pieces of the cake known to still be in existence.

A larger piece of cake housed in an exquisite, custom-made gold-plated casket has recently come to light and, at time of writing, is in the possession of Daniel Bexfield Antiques (see link below). According to engraving on the casket, this portion of cake was a gift for Mr W.S. Charles from Lady Cust, whose husband, Sir Edward Cust, was the Royal Master of Ceremonies so would have had an instrumental role in the wedding itself.

The Marriage of the Prince of Wales, 1863 by an unknown artist after William Powell Frith (oil on canvas, courtesy of the Walker Art Gallery in Liverpool, released under Creative Commons license)

The Wedding

Although the wedding on 10th March 1863 between Edward, Prince of Wales and Princess Alexandra of Denmark was a grand affair, it was very much overshadowed by the sudden death of Edward’s father, Prince Albert, in December 1861. A distraught Queen Victoria refused to emerge from deepest mourning. She apparently only allowed the wedding to take place within the customary two-year period of court mourning because Prince Albert had been very keen on the union and arrangements were already underway at his death. At her insistence, the wedding was smaller than would be usual for an heir to the throne, and women guests were expected to wear the muted ‘half-mourning’ shades of grey and lavender as a mark of respect. The Queen herself, garbed in swathes of matt black to reflect her mood and depth of mourning, watched the ceremony from a private balcony rather than join the congregation.

Queen Victoria, Prince Edward and Princess Alexandra photographed with a bust of Prince Albert soon after the Royal Wedding in 1863 by John Jabez Edwin Mayall (carbon print, courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery, London NPG x36269)

Edward and Alexandra’s marriage

As Queen Victoria’s eldest son, and therefore heir to the throne, Prince Edward had long been a cause of concern to both his parents. Known as Bertie, he had an international reputation as a playboy with a string of unsuitable mistresses. Queen Victoria and Prince Albert were desperate for their son to marry and settle down and had trawled through the eligible princesses of Europe to try and find a suitable match. They decided on Princess Alexandra, the eldest daughter of the heir to the Danish throne. At the time of their wedding Edward was twenty-one and Alexandra was eighteen.

Alexandra was stunningly beautiful and her dress-sense was much admired. In public she was charming and graceful, and in private she was vivacious, warm-hearted and accomplished. The couple went on to have six children and an outwardly happy relationship although Bertie, later King Edward VII, did not reduce his appetite for illicit liaisons and is thought to have had about fifty-five mistresses during his marriage, including the actress Lily Langtry. As king, however, Bertie was a popular monarch with a highly visible public presence compared with his reclusive mother.

After forty-seven years of marriage, Alexandra was by Bertie’s bedside when he died in 1910, and she lived a further fifteen years as Queen Mother to their eldest son King George V.

Small piece of cake with average-sized curator's hand

Back to the cake …

Frustratingly, we are no nearer identifying who Miss D was, and how the sewing box (complete with cake) arrived at the VG&M is something we are still researching. We believe it may have come from the Gregson Memorial Institute in Wavertree, an educational establishment founded by Isabella Gregson in 1897 in memory of her family. The collections it housed were later dispersed with a substantial part coming to the University of Liverpool. We intend to solve this puzzle soon!

Further information on:

Daniel Bexfield Antiques: https://www.bexfield.co.uk/

The wedding of Edward, Prince of Wales and Princess Alexandra:

Keywords: Royal Wedding 1863, Royal Wedding cake, Prince Edward and Princess Alexandra, King Edward VII, Queen Victoria.