Alfred Waterhouse and the Victoria Building

By Martin Strauss, VG&M Volunteer

Download the PDF Alfred Waterhouse and The Victoria Building by Martin Strauss

Alfred Waterhouse’s long association with Liverpool University College began in 1881. By 1899, he had altered or built eight buildings for the College, at a total cost of about £136,000 (c £8.0m today). His proven and extensive experience in designing academic institutions, notably at Oxford, Cambridge, Leeds and Manchester, his standing as a major architect in Victorian Britain and the fact that he was born in Liverpool (in Everton in 1830) and was well-known to many of the city’s prominent leaders, made him the ideal candidate to design the College’s most important building, to commemorate Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee. For the Council, the choice was an easy one – Waterhouse had already designed a new Infirmary for the City, two new buildings for the College and adapted the old Asylum for use in 1881. How the Asylum came to be used at all is part of a wider story, involving various attempts to set up a ‘higher education’ college in Liverpool in the 1850s and 1860s.

Several meetings had taken place during these decades, involving the Headmasters of the Royal Institution, Liverpool Institute and Liverpool College, together with representatives from the Infirmary Medical School ( notably TH Waters and J Campbell Brown), as well as many other interested independent men and women. In the University’s ‘Precinct’ magazine for May 1978, The University Archivist, Michael Cook, notes that Liverpool lacked a pre-eminent patron as was found in other cities, so that “ the story of higher education in the city involves most of the city’s educated elite, in particular the school of non-conformist learning which centred on the Unitarian Congregations.” In 1866, the Liverpool Ladies Education Association was formed to promote women’s education. In 1874, The Association to Promote Higher Education in Liverpool was formed, with plans to link up with the Cambridge University Extension scheme of lectures and degrees. Several members of this Association would play an important part in the foundation of the University College: William Rathbone, MP, for many years a major philanthropist in the city, had set up a training school for nurses at his own expense; George Holt, ship-owner and philanthropist; Charles Beard, Minister at the Unitarian Church in Renshaw Street, committed to promoting education and literacy; Christopher Bushell, retired wine-merchant and Chairman of the Liverpool Elementary School Board and Edward Lawrence, Conservative Councillor, past Lord Mayor, businessman and politician. Rathbone and Holt, both much involved with the Liverpool Institute, were members of Beard’s congregation. In November 1877, The Association and the Council of the Medical School met and elected a Committee to set up a proposed College of Science; but on December 3rd, Beard, leading a sub-committee, went for a much broader proposal to set up a College for Arts and Sciences, which would include evening classes as well as day students. Then, at some point in the next few months, Rathbone approached the Lord Mayor Mr (later Sir) AB Forwood (ship-owner and leader of the Conservatives on the Council) to summon a ‘Town Meeting’ to discuss the proposed College.

At the ‘Town Meeting’ held in the Town Hall on May 24th 1878, steps were taken to establish a University College in the city. As the College Principal later pointed out in his inaugural address, other large cities had already or were creating their own University Colleges: Bristol, Leeds, Sheffield, Nottingham, Newcastle and Manchester. Liverpool had to look to its laurels. Further impetus for such a course came in a speech by Canon Lightfoot, Bishop-elect of Durham on January 16th 1879, where he outlined his visions of the future of education in Liverpool. At the Town Hall meeting, a resolution to set up a College was proposed by Lawrence, seconded by Waters and carried enthusiastically. A Committee of thirty was set up to take the idea forward, under the leadership of the Lord Mayor. In practice, the work was undertaken by a sub-committee chaired by Edward Lawrence, with Rev Charles Beard as Vice chairman, Robert Gladstone as Treasurer, James Campbell Brown as Hon Secretary, with Sir James Picton, Chairman of the Liverpool Library Committee, Christopher Bushell and his son, Reginald, W and SG Rathbone, GF Lyster (chief port engineer) and Malcolm Guthrie, a silk mercer. They proposed to create seven professorial ‘chairs’ and estimated the costs of setting up a College at £75,000, not including a site or any buildings which might be needed. The College was to be non-denominational. The number of prominent Conservatives and Anglicans involved also helped to avoid the criticism that the College would be a Liberal and non-conformist institution. The Committee proposed to establish three Arts and four Science professorships, with lecturers in law and physiology; no languages were to be taught and all medical subjects were to be taught at the Medical School. Kelly suggests that the founding fathers of the new College should be seen as Rathbone, Campbell Brown and Beard, with the last being perhaps the most articulate advocate. Rathbone was instrumental in getting financial commitment from local men and Campbell Brown lent his academic and local prestige to the process.

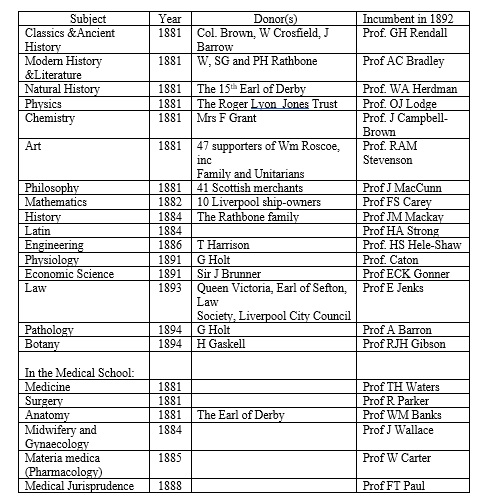

The new Committee now took four important steps. First, a site was found in Ashton Street, where the Old Asylum had closed, when plans were announced to drive a long railway cutting from Edgehill through its grounds into Lime Street Station. The City Council enabled the College Council to acquire the land and the Asylum, for a sum of £19,000, which was initially guaranteed by Mr Thomas Cope, a tobacco manufacturer. The College Annual report says that the Committee “secured the building and four acres of land”. In fact, on September 7th 1881, the City Council agreed to apply to Parliament for £30,000 to purchase land and buildings already secured by the College. This power was obtained in 1882 by the Liverpool Improvement Act, so that the Council was able to give the site to the new College Council. Secondly, Waterhouse was retained to adapt the two-storey building and in 1881 he produced plans and drawings. Thirdly, a campaign was launched to raise money to endow chairs for various professors and to fund building costs. The response to this and to later fund-raising in the city was magnificent (see some details in Appendix 6); industrialists (many of them chemical and food manufacturers), ship-owners, philanthropists, businessmen and aristocrats proved most generous so that by 1881, before the College opened, seven chairs had been endowed: The King Alfred Chair of Modern Literature by William, Samuel and Philip Rathbone; The Derby Chair of Natural History by the Earl of Derby; The Gladstone Chair of Ancient History by Alexander Brown, William Crosfield and James Barrow; The Roger Lyon Jones Chair in Physics from the Roger Lyon Jones Trust; The Grant Chair of Chemistry by Mrs F. Grant in memory of her brother, Lloyd Rayner; The Roscoe Chair of Art, by various member of William Roscoe’s family and of the Unitarian community; and Philosophy, by a group of forty-one Scottish merchants. One account of this process suggests that fund-raising was slow until Rathbone returned to Liverpool after the 1880 General Election; he immediately set about persuading prominent men to endow chairs and commit money to the College. In his Memoirs, he says that £80,000 was raised by 1881. Kelly says that £109,171 was raised by 1882.

Finally, on June 11th 1881, The Committee appointed a Principal – Gerald Henry Rendall, Fellow and Lecturer in Classics at Trinity College, Cambridge; it was to prove an inspired choice. He was also appointed to the Chair of Classics and Ancient History. In an article in the Liverpool Review of 1892, Rendall describes how he was interrupted during a May Day lunch in Cambridge by three visitors from Liverpool: William Rathbone, Bushell and The Rev. Beard. They had come to offer him the post of Principal. Rendall also notes, in looking back from 1892, the tremendous civic spirit and local patriotic pride in the city in the 1870s and 1880s, when some £250,000 was raised by donations from the citizens. He also comments on the strong movement for education in Britain at the time and since, especially in scientific and technical subjects. In fact, many of the supporters of the College were already supporting Elementary education in Liverpool (after the Education Act of 1870), notably Rathbone and Bushell.

A further important step was taken when the new College received its Charter of Incorporation on October 18th 1881. This established a Court of Governors with a Council, representing those Governors, in practical control of the running of the College. There was also a Senate, being the College Professors. The Earl of Derby was President; William Rathbone and Christopher Bushell were Vice-Presidents, with Robert Gladstone as Treasurer; Edward Lawrence was appointed Chairman of the Council, with Charles Beard as Vice-Chairman. The other members were Arthur Forwood, Sir James Picton, Samuel Rathbone, William Crosfield, Samuel Smith, AT Squarey, Reginald Harrison, Revd George Butler and Thomas Cope. Further men joined soon after: Malcolm Guthrie, Edmund Muspratt, Sir David Radcliffe and William Laird. Many of these were great benefactors to the College (see Appendix 6).

One other issue lies at the heart of the College’s formative years. In 1875, Owen’s College in Manchester wished to set up as The University of Manchester. Yorkshire College in Leeds and Liverpool Medical School both objected since they feared that this would give Manchester a monopoly of degree awards, especially in medical subjects. Owens College relented and proposed a Federal University. This was set up in April 1880, by Royal Charter, to teach to degrees in Arts, Sciences, Law and Music, but not in Medicine. Liverpool University College joined in 1884 and Leeds in 1887. Victoria University existed until 1903.

In addition to the reasons suggested above for Waterhouse’s appointment as architect in 1878, he had also established his reputation with other Liverpool buildings: The Lime Street Hotel and The Seamen’s Orphan’s Institute in Newsham Park. Of some significance perhaps was that he was known professionally to Bushell, for whom Waterhouse had built Hinderton Hall, near Neston in 1856 and Edward Lawrence , whose house Waterhouse had altered in Barkhill Road in 1865. He had also built a house for Lloyd Rayner. Rendall would have known his Cambridge buildings too. Of course, by 1878, Waterhouse had become famous for buildings of national and civic importance in London, Manchester and elsewhere.

In addition to the reasons suggested above for Waterhouse’s appointment as architect in 1878, he had also established his reputation with other Liverpool buildings: The Lime Street Hotel and The Seamen’s Orphan’s Institute in Newsham Park. Of some significance perhaps was that he was known professionally to Bushell, for whom Waterhouse had built Hinderton Hall, near Neston in 1856 and Edward Lawrence , whose house Waterhouse had altered in Barkhill Road in 1865. He had also built a house for Lloyd Rayner. Rendall would have known his Cambridge buildings too. Of course, by 1878, Waterhouse had become famous for buildings of national and civic importance in London, Manchester and elsewhere.

The alterations to the Old Asylum would provide teaching space and administrative rooms for the Principal, Registrar and Professors. At a conversion cost of £20,000, the new University College opened on January 14th 1882, with forty-five students. In his inaugural address, Principal Rendall drew attention to the ‘unprecedented’ sums promised and given by benefactors. He noted that Liverpool already had first-rate educational establishments in The Royal Institution, The Liverpool Institute and Shaw Street College (Liverpool College, founded in 1840) and extensive primary school provision. There were science and art colleges, public reading-rooms, lecture halls as well as literary and scientific societies in the city. He drew attention to Liverpool business and medical achievements, together with other social improvements. But he also said that “(at present) academic training is only for the privileged and wealthy”. He concluded that it was a good moment to open a University College to satisfy civic pride and offer opportunities for young people. “(....the College will contribute to making Liverpool of the future appreciably happier, richer and wiser.....”).

The re-developed Asylum served to accommodate Natural History, Physics, Engineering, Architecture, Modern Literature and Law together with rooms for the Principal, the Registrar and the Council, a lecture theatre, library, reading-room, Ladies common-room and professors’ common-room. All the medical departments were located in the Royal Infirmary School of Medicine in Dover Street and this became the Medical Faculty of University College in June 1884. The new building soon proved to be too small, as numbers in the College grew in 1883-4 and Waterhouse was asked to provide new buildings for Chemistry and Engineering, at the same time the Governors of the Liverpool Infirmary commissioned him to build a new Infirmary on the same site. This all took time and while it was clear that new specialist buildings would help to ease the overcrowding in a few years, it was also clear to the council that the Asylum was inadequate for the numbers of students enrolling in the new College. Principal Rendall drew attention to all this in his annual address in the autumn of 1884. Accordingly the Council decided to build again, this time a building for the Arts subjects.

After the College had joined Victoria University in 1884 and with the approach of Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee in 1887, it seemed an appropriate moment to plan a building in her honour. Waterhouse was commissioned yet again for a building which would provide an administrative headquarters for the College as well as teaching and reading rooms. On March 1st 1887 the Council set up a Building committee to see this through. The records of the meetings of the Committee are contained in a small brown volume; forty-one meetings are recorded up to October 1893 and it seems clear that by the time of the first recorded meeting, on June 6th 1887, Waterhouse had already submitted some plans and elevations for consideration. No doubt excited by the new project, the Building Committee met three times in June 1887 (6th, 14th and 23rd), but thereafter meetings were less regular- only three more in 1887; five in 1888; seven in 1889; three in 1890; seven in 1891 and five in 1892. The Committee was chaired energetically by Principal Rendall with several Professors and other long-term supporters of the College, George Holt for example.

Two early problems which faced the Committee and caused some disagreements were the location of the main entrance on Brownlow Hill and the placement of the building line along the street. Indeed on June 14th it was proposed that Rendell actually go to London to see the architect on these matters! In fact Waterhouse himself came to the meeting on the 23rd of June to talk through the problems and discuss elevations, light sources and the theatre, for which he brought plans to seat four hundred. During July and August, he submitted more plans and elevations based on the points arising in June, so that in September the College was able to launch a public appeal for funds, publishing a leaflet with an illustration of the proposed south front on Brownlow Hill. The minutes of the Committee do not mention any costs until January 1889, but from other sources it seems that the budget set for the building was £35,000 and that the building could be put up in three blocks, depending on available funds, that is The Theatre (10k), The Hall (10k) and the Library (15k). However with the generosity which had characterised earlier fund-raising, it was clear during 1888-9 that the whole building could be erected at once. By June 1888, the Committee had some £16,000 in hand and by November 1889, £38,000 (although costs had risen, as we shall see).

No serious difficulties impeded progress in 1888, although much discussion continued about the building-line, windows (shape and size),entrance, location of coal-chutes, provision of furnaces, sound-proofing measures and provision of lavatories (the first plan was to house the facilities for men in the new building and for women in the Old Asylum, with a covered way to link the two!). In the Autumn of 1888, the main Brownlow elevation had been decided, meetings had taken place with the Liverpool Jubilee Tower Committee and in November, Henry Tate had offered £16,000 for the new Library. In the same month, tenders were put out for excavations and foundations; Waterhouse was to seek permission to build over the railway cutting and organize a supplier of terracotta and a sub-committee was set up to decide on the best heating and ventilation system, whether steam, high-pressure hot water or hot air. (The search for permission to build over the cutting sounds a bit late in the day, with plans already draw up for the size and location of the building, but it may be Waterhouse did not see a problem as he knew well one of the Directors of the London and NW Railway Company, Mr J Tipping, who had been instrumental in getting Waterhouse the Lime Street Hotel commission and for whom Waterhouse had built a house in Kent. In any case the recently erected Walker Engineering Building also spanned the cutting.) In January 1889, with Waterhouse present, the building line issue was finally resolved and the cheapest tender for the foundations was accepted from Isaac Dilworth of Wavertree for £1890; the highest figure was £2400.

In the early part of 1889, minutes deal with lighting (natural and artificial), window-size, gates and coal-storage. The covered way was abandoned and sanitary provision made in the new building for men and women. In June, tenders for the main building were considered, that is the Library, Tower and Theatre. From the eight firms tendering for the work, Brown and Backhouse of nearby Chatham Street were chosen, once Waterhouse had assured himself that their carpentry and woodwork proposals were satisfactory. In July, the Committee recommended that the Council accept their tender of £38,664. This was the cheapest tender and was made up of: £23,687 for Library and Hall; £4,018 for the Tower and £10,959 for the Theatre. Other tenders included £39,150 from Dilworths and £40,230 from R.Jones (who had built the Chemistry laboratories). In November, the Brown and Backhouse figure rose to £38,964, when they appointed new sub-contractors, Joshua Henshaw, also of Chatham Street. A further sum of £7,720 was reserved for consideration on faience, mosaic flooring, library fittings, gas fittings, bells and speaking tubes, these and other items being costed in the minutes. At this stage, the costs seemed to have been about £46,000: the foundations and buildings as above, with £2,000 architect’s commission, £350 for the Clerk of Works, £2,000 estimated for furniture and £1,000 for the clock in the Tower.

At this juncture in the history of the Victoria Building, another source of information helps us to understand the progress of the construction and the problems which arose. This source is the collection of letters which Principal Rendall wrote to Waterhouse between 1889 and 1893. They are all hand-written and held in a bound leather volume. An interesting picture emerges of Rendall’s role in the programme of building and his strong commitment to the project. Reading ‘between the lines’, he had a number of areas of dispute with members of the Committee and his letters often sought Waterhouse’s help in resolving these. The architect’s replies are not to be found, but from the sense of Rendall’s letters, he must have worked hard to modify his ideas and provide new plans to satisfy his clients. I suspect this is a good example of why Waterhouse was so successful as an architect – he tried hard to please his clients, while retaining his own vision of the building. Whereas he has been seen as a man careful with his clients’ money, in the case of the Victoria Building he was determined to scupper the Committee’s plans for a cement render on the walls, in favour of tiles and faience, which no doubt put up the cost, but was eminently worthwhile. (See Appendix 5 for more information about the content of the letters and Appendix 1 for a list of contractors).

At this stage of the building, on November 1st 1889, once Waterhouse has asked for £130 for drainage improvements and resisted the cement render idea, the costs are noted at £46,536, rather more than the original estimate of £35,000. Oak flooring was to be installed throughout, with library fittings in oak as well, as requested by Henry Tate. (Rendall wrote to him in 1889 with a request to increase his already generous contribution, which he did and a further £4,000 was promised to cover the cost of the oak. Also of note at this point, December 1890, is the first appearance of Paul Waterhouse in the minutes; he had recently joined his father in the practice and was invited to design some of the (unspecified) library fittings.) Another local firm, George Gilbert of Bold Street won the commission for library, office and theatre chairs (£2.4s without arms and £2.14s with). In March 1891, tenders were put out for gas and electric fittings, cables and pipes; two more rooms were to be incorporated in to the top floor by re-arranging the staircase; the Electricity Supply Company of Liverpool was brought in to install cables and light fittings and in October 1891 Mr Reginald Bushell, son of the past Vice-President Christopher (who had died in February 1887) provided estimates for the bells from Taylors of Loughborough (£629) and the Tower clock from Potts of Leeds (£357). These estimates were accepted and the cost of both to be borne by Mr William Hartley, jam manufacturer, of Aintree. At this meeting in October 1891, it was indicated that the building would be ready for opening around Easter 1892 and plans were put in hand for the opening ceremony.

The next few meetings of the Building Committee discussed matters such as the number of light fittings required in the building (later fixed at one hundred and fifty-five at a cost of £130), final sizes of some rooms, installation of telephones, linking clocks in the building to the clock in the Tower and ordering blinds for lecture and office rooms. However early in the New Year it became clear that the building would not be ready in time for Easter and the invitation to the Prince of Wales had to be withdrawn. In May, it was known that the faience contractor could not finish before August, while late costings included £378 for landscaping in the quadrangle, £365 for further Library furniture and £52.8s for wiring. Waterhouse now arranged for painting to be done and final accounts were to be drawn up (see below). The Ladies Committee was permitted to raise funds to decorate their Common-room and a bookcase in the Library was made available to the Teachers Guild (May). Mr Bruce Joy’s statue of Christopher Bushell was to be put in place in the entrance hall of the new building– this fine sculpture was financed by money raised in the city in 1885 as a testimonial to Bushell, to honour his work over many years in promoting and supporting education in Liverpool, as well as teacher-training. (The statue had been in The Liverpool Free Library in William Brown Street). Rendall also arranged with Waterhouse for some fireplace surrounds in his and other offices to be inscribed in Latin or Greek, for which the Principal himself paid (two are still in place).

On October 30th 1892, the Building Committee drew up the following statement on costs:

Report of Architect £44,555

Electrics £446

Gas meter £22

Grounds and gateway £290

Inscription plates £76

Painting £198

Grate £3

Clock and bells £1,001

Furniture £3,045

Architect and Clerk of Works £3,262

Telephone £43

Water meter £5

Mains to Walker Labs £64

Sundries £50

Total £53,064 (+ 7s 5d)

Report of Architect £44,555

Electrics £446

Gas meter £22

Grounds and gateway £290

Inscription plates £76

Painting £198

Grate £3

Clock and bells £1,001

Furniture £3,045

Architect and Clerk of Works £3,262

Telephone £43

Water meter £5

Mains to Walker Labs £64

Sundries £50

Total £53,064 (+ 7s 5d)

At the meeting on November 24th 1892, Waterhouse thought that £53,000 would about cover it. He proved a little conservative in his estimate as ‘extras’ were added in 1893. However to judge from the minutes, the Victoria Building must have been very nearly complete when the opening ceremony was held on December 13th 1892. The Vice-Chancellor of Victoria University, Earl Spencer performed the relevant duties.

A degree ceremony was held the next day in St George’s Hall, with a reception for three thousand people. Unfortunately, the President of the University College, The 15th Earl of Derby, was prevented from attending by illness and the ‘Derby Window’ can be seen as a memorial to him after his death in March 1893. The Council report of 1893 shows that the opening ceremonials cost £377. 14s. 4d (£22,620), which sounds a suitably lavish occasion with which to open a fine building.

“For the advancement of learning and ennoblement of life, The Victoria Building has been raised by the men of Liverpool in 1892”. The plaque on Brownlow Hill makes clear the purpose of the new Gothic Revival edifice. Although there was more to do, the College Council must have been well-pleased as the New Year arrived in 1893. The membership of the Building Committee had changed slightly over the years but among long-serving members apart from Rendall himself, were George Holt, Professor Lodge, Professor Herdman, Professor Hele Shaw, Professor MacCunn, Mr Robert Gladstone and Mr William Rathbone M.P. These men and their architect had argued over all manner of matters during the planning and erection of the Victoria Building. No doubt disputes were argued cogently and vehemently. Quite clearly Rendall was the driving force, proving himself to be a sound businessman over the years – he served as Principal until 1898, when he moved to be Headmaster of Charterhouse. Most of the buildings erected during his term of office survive. Before Rendall moved on, he, Waterhouse and William Rathbone had all received Honorary Doctorates in May 1895 from Victoria University, in recognition of their work in nurturing Liverpool University College through its early years.

Documentary evidence on the Victoria Building after the opening in 1892 continues in the form of Rendall’s letters, minutes of the Building Committee (four more meetings are minuted) and the College Council Annual Reports published in October. From the report of 1892, we can note that the City Council has given grants for the electro-chemical department and for evening lectures for artisans, The Liverpool Law Society has supported the Law faculty, George Holt has given £5,000 for the maintenance and development of the Physiology Laboratories and Charles W Jones has provided a field close to his Wavertree house for use as sports ground (cricket, tennis, football and lacrosse) – this is recognized in the fine plaque by Charles Allen on the staircase.

Meanwhile in the Victoria Building, folding doors in the Arts Theatre created an annexe room and Rendall came up with a scheme to remove some sections of staging for examination use. Telephone links were made throughout the building and the Old Asylum had been overhauled for use by the Physics, Biology and Botany Departments. Henry Tate has made a further grant for books in several Departments and more books had been bought with money from the George Holt and Herbert Campbell Funds. Liverpool City Council had made grants to promote technical and commercial education, areas which attracted a good deal of funding in Britain in this last part for the nineteenth century; Engineering received £250, as did Chemistry, with £750 to Physics; Scholarships were also endowed in these three subjects. Further funding for chairs was noted by the Treasurer, whose report showed that money was invested in Mersey Docks Bonds, Canadian and Bengal railways and Liverpool Corporation Stock among others.

Committee minutes now mention the connection of the water tank in the Tower (6000 gallons) to all parts of the building; more chairs were needed for the library and theatre; photographers, Robinson and Thompson, had prepared ten portfolios of drawings and photographs, Waterhouse had presented the actual drawings (for which he charged twenty-two guineas!) and proposals had been produced by Mr Rowlands for the ‘Derby Window’. Waterhouse was asked to design a bicycle shed – an unusual request even for him! This was later changed to a ‘lean-to’ which probably did not require his expertise. (Incidentally many of the smaller building tasks and internal fixtures were done by the College’s own workforce – lockers and fittings in the common rooms and porter’s lodge, for instance.) Mr James Battye, the clerk of Works on this College project and others in the 1880s and 1890s, was awarded a payment of £40 for his work on the Victoria Building. Presentation albums were given to Alfred Waterhouse, Henry Tate, William Rathbone and Edward Lawrence (Chairman of the Council). Some final figures are given in the penultimate meeting of the Building Committee:

Receipts: £52,066.7s.10d; Disbursements; £53,766.13s.5d.

The final and forty-first meeting took place on December 12th 1893, when some minor changes were made to the design of the ‘Derby Window’. The Minute Book has one hundred and seventy-five pages, though mostly recorded on the right-hand page. Waterhouse attended eleven of the forty-one meetings; no doubt he took time when in Liverpool to look at his other work in the city (The Prudential Building in Dale Street) and he would continue to be involved at the University College with Medical, Chemistry and Anatomy buildings until 1899, though increasingly Paul Waterhouse would be involved in these later works.

The Council Report of 1893 takes the history of the building a little further, with details of donors to the building fund, the distribution of teaching rooms in the Victoria Building, the benefits of the new building after nine months of use and details of the numbers of students in various subjects (see Appendix 3). One hundred and forty-five donors to the Building Fund are listed, with amounts varying from £20,000 to £1. Among the donors may be cited:

Henry Tate £20,000

George Holt £2,000

The Earl of Derby £2,000

William Hartley £1,133

Henry Tate (junior) £250

The Duke of Devonshire £150

Alfred Waterhouse £105

The Duke of Devonshire was Chancellor of Victoria University. Hartley’s contribution had been for the clock and bells. The late Earl of Derby had left £2,000 in his will for scholarships. It is good to see the architect having faith in his own building and supporting education in his native city. Women students had contributed £184, while the men had contributed a mere £51!

The Victoria Building had been built to house the Arts subjects in the College. On the ground floor, German, Maths and Latin; on the first floor, Greek, History, Philosophy, Italian and Modern Literature; on the second floor, English and Economic Science; on the third floor, Art. The Council notes that the building has given the College more room for teaching and to allow lectures to start on time! The Common-rooms and reading-rooms are excellent facilities; the theatre, seating four hundred and fifty, has been used for student entertainments, public lectures and public meetings. The Council reports that the Administrative offices should have been larger, but concludes: “The Victoria Building is well-adapted for its purpose, satisfactorily warmed and ventilated and suffices for all central needs”. In his own section of the report, Principal Rendall stated “ The completion of the Victoria Building has completely changed the working conditions of student life”.

No doubt this was what Waterhouse would have wished to hear, but it is not surprising, given his reputation, to read these comments about his building. On a gloomy note, the Council writes that the College is in debt by £5,000. They have plans in the 1890s to build an examination hall and extend the building along Ashton Street, but these particular ideas were not realised. Other details in the Report for 1893 show that public lectures have been given on Classics, History, Languages, English, Chemistry and Maths and a decision has been taken in the city to found a School of Architecture and Applied Art. (At the College, the Roscoe Chair of Art was now applied to Architecture, with F.M. Simpson appointed to the Chair in August 1894, to be succeeded by Charles Reilly in 1904.) The Report contains twenty-five pages of book acquisitions to the Tate Library and Rendall has given an autographed portrait of Alfred Waterhouse to the Library. Income from student fees is noted at £6,082, excluding medical students. Grants continue from the City Council towards the Electro-technical Department and Lancashire County Council has also supported teaching at the College.

The Council report for 1893-4 mentions that the 16th Earl of Derby has become the new President of the College in succession to his brother and the Derby window has been put in place in the Main Hall. Four new Chairs have been endowed in Botany, Law, Pathology and Anatomy, with donations to new Laboratories. This year forty-eight pages of books are listed (with a special tribute to Henry Tate’s generosity in this respect). Student fees are noted at £6,727. The donation of books is continued in the report for 1894-5, with twenty pages and, in addition, thirty-six pages of the Thom Bequest, some three thousand books from the Rev John H Thom, a long-time supporter of the College. Books have been received from the library at the Royal Institution, Colquitt Street. Student fees are £6,515 and Professors salaries are £9,737.

This report gives a brief history of the College since 1881 and cites the major donors. By 1895, the College had 17 Professors, 2 Professors Emeriti, 5 Medical professors and 31 lecturers/demonstrators. A three-term year begins on October 4th and ends on June 29th, with examinations in December and March. Students must be at least fifteen years of age and those under sixteen are subject to an entrance examination; the Medical School is for male students only. Degrees were awarded by the Victoria University and London University. £5.00 studentships were available to enable working men to study.

The Victoria Building is a good example of Alfred Waterhouse’s ability to plan a large-scale building for a particular purpose. In its obituary notice in 1905, The Manchester Guardian observed that Waterhouse’s buildings “were always strong and individual......essentially typical of the age in which he lived and the people for whom he built”. Gothic Revival was judged appropriate for Universities and Colleges in late nineteenth century Britain, as is testified at Oxford (for example, Keble College by William Butterfield), Cambridge, Leeds, Manchester, Bristol, Birmingham and elsewhere. Gothic chimed with the Christian traditions of Western Europe and the strong Anglicanism of the period. It has been noted that the main hall in the Victoria Building has an apse-like design at one end, with a corridor behind and balcony above. Some features were no doubt taken from older universities, such as creating a quadrangle, the lay-out of the Library and the imposing entrance and central hall.

As the College and, after 1903, the University has expanded since 1892, so the uses of the Victoria Building have changed, as various departments moved out to their new subject buildings, the Library moved to new premises in the Cohen Library and administration has moved to Senate House and other buildings. Yet it has always found a purpose, whether as an examination centre, a display centre for the University’s collection of ceramics or for smaller departments. Visitors to the new Gallery and Museum are invariably impressed with the building, while expressing ignorance about its existence and its architect. The conversion in 2008 was an important contribution to Liverpool’s ‘Year of Culture’, since it guaranteed the continued existence of one of the city’s finest buildings and a fine example of the work of Alfred Waterhouse.

Post-script..

With The University College in its infancy, there was much to do and the Council was very keen to set up sufficient departments to offer a wide range of subjects. In the 1880s, specialist buildings had been set up for Engineering and Chemistry. In the 1890s, more Chemistry laboratories were built (The Gossage Laboratories) and The Thompson-Yates Buildings for the Medical School. In March 1899, the Committee on College sites reported to the Council and outlined what they felt were essential tasks in the years ahead. The Medical School extension was in the process of completion (on which Paul Waterhouse was engaged). Further the Committee wrote of the need for buildings for the School of Architecture; more lavatories; buildings for Physics, Electrotechnics, Botany and Geology; a refectory; a Students’ Union and a gymnasium; they also noted that the Tate Library was frequently crowded. A small lecture hall was needed for two hundred to two hundred and fifty students and a separate examination hall. Student numbers had increased considerably and more teachers were being trained. Professors Simpson and Carey outlined plans to extend along Ashton Street; Professors Lodge and Herdman made suggestions about Zoology/Botany and Physics/Electrotechnology.

In April 1901, the College Council printed a pamphlet which outlines plans to secede from Victoria University and establish a separate University of Liverpool. At this time there were 26 Professors and 60

Readers/Lecturers/Demonstrators, with 700 students and 1100 different day and evening classes.

The College had capital investments in land and buildings to the value of £500,000; a £3000 grant from the Treasury, £1800 from Liverpool City Council and £250 from Lancashire County Council. New capital would be needed to finance the projects mentioned in the 1899 Report cited above, together with Professorships in Modern languages and Applied Science.

In time some of these proposals were realised. The Hartley Botanical Laboratories were opened in May 1902. The George Holt Building (Willinck and Thicknesse, with FM Simpson) was erected in 1904. In 1905, a Zoology Museum and attached laboratories were ready, also by Willinck and Thicknesse. They also designed the Derby Electrotechnical Buildings in 1905 and in May 1912, the Harrison-Hughes Engineering Building opened, with donations of £40,000 from shipowners Thomas Harrison, Heath Harrison and John Hughes. Also in 1912, the Ashton Building for the Arts opened next to the Victoria Building in Ashton Street. At some point between 1908 and 1912, the old Asylum was demolished and the present quadrangle laid out.

Before most of these were erected, The University College had seceded from the Victoria University in 1903 to become The University of Liverpool. I found a memorandum from the University to the Liverpool City Council, dated January 15th 1904 and signed by The Earl of Derby (President), Professor Dale (Principal) and HR Rathbone (Treasurer). The University requests a grant of £20,000 to build on earlier successes and realise some of its building and academic objectives. The document re-tells the history of the University College since 1881 and once again records the generosity of past donors (presumably to encourage the Council to follow their example!).

As the University moved into an independent era, Alfred Waterhouse, though unwell after his stroke in 1902, could look back with great satisfaction on his time in Liverpool, the city where he was born, with private houses, institutional, commercial and university buildings to his credit. Of these, only two of the private houses and two university buildings have been demolished, but the remainder are witness to Waterhouse’s vision and abilities as an architect. Apart from Park Hospital in Newsham Park, which has been empty for many years and has an uncertain future, all his buildings are in use.

Appendix 1a.

Main Contractors for the Victoria Building.

Foundations - Isaac Dilworth, Wavertree

Superstructure- Brown and Backhouse, Chatham Street

Structural steelwork - A. Handyside and Co

Modelling - Farmer and Brindley; Earp and Hobbs

Faience and tiles - Burmantofts, Leeds

Mosaic flooring - Jesse Rust

Chimney-pieces - Hopton Wood Stone Co; J and H Patteson

Ironwork - Hart, Son, Peard and Co**

Furniture - Gilberts, Bold Street

Heating - G.N.Haden and Co**

Terracotta - J.C.Edwards, Ruabon

Clock - Potts, Leeds

Bells - Taylors, Loughborough

Superstructure- Brown and Backhouse, Chatham Street

Structural steelwork - A. Handyside and Co

Modelling - Farmer and Brindley; Earp and Hobbs

Faience and tiles - Burmantofts, Leeds

Mosaic flooring - Jesse Rust

Chimney-pieces - Hopton Wood Stone Co; J and H Patteson

Ironwork - Hart, Son, Peard and Co**

Furniture - Gilberts, Bold Street

Heating - G.N.Haden and Co**

Terracotta - J.C.Edwards, Ruabon

Clock - Potts, Leeds

Bells - Taylors, Loughborough

**also worked on the conversion of the Asylum, 1881-1883.

Appendix 1b.

Table to show Waterhouse’s first use of some of these contracting firms.

Hart and Son, Peard and Co 1854 Rothay Holme, Ambleside. Ironwork

J and H Patteson 1856 Hinderton Hall, Neston. Chimney pieces

Farmer and Brindley 1857 Bradford Old Bank, Bradford Stone carving

Hopton Wood Stone Co 1858 Fawe Park, Keswick Chimney-pieces

G N Haden 1859 Manchester Town Hall Heating and ventilation

Heaton Butler and Bayne 1859 Manchester Town Hall Stained Glass

Jesse Rust 1875 Pembroke College Cambridge Mosaic for clock dial

Burmantofts 1876 Prudential Assurance, Holborn Faience

The Victoria Building has the benefit of over forty years collaboration between the architect and many firms, whom Waterhouse had come to trust and know over numerous commissions.

Appendix 2.

Waterhouse’s other commissions between 1887 – 1892.

While the Victoria Building was being planned, discussed, refined and built, the Walker Engineering Laboratories were also being completed next door and the Chemistry Laboratories erected in Brownlow Street.

Elsewhere, Waterhouse was building a total of thirty-five projects in seventeen different towns and cities: London, Manchester, Brighton, Middlesborough, Rugby, Reading, Cambridge, Stanmore, Leicester, Guisborough and in Kent and Buckinghamshire.

For the Prudential Assurance Co, he built offices in Glasgow, Birmingham, Leeds, Newcastle and Cardiff; these offices cost between £16,000 and £45,000.

Appendix 3.

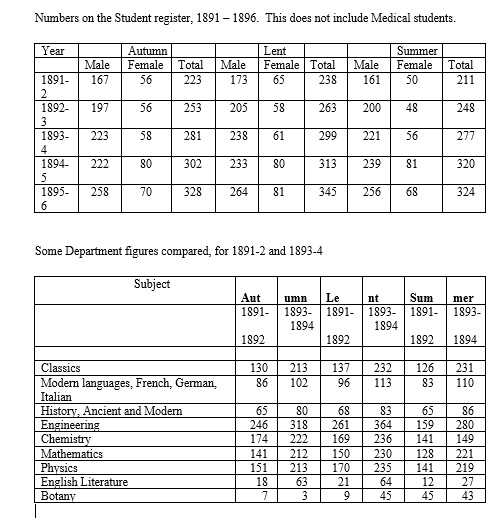

These are taken from the Council Year Books. I have omitted some subjects e.g. Art, Biology and Economic Science. There were seventeen professors in 1894, so at least that number of subjects.

Engineering students appear to outnumber the total number of students in these years!! I think this may be explained by the fact that the Council Report has included in the department figures students who enrolled in evening classes, which were very popular from the beginning of the College’s life. Incidentally, Rendall placed no limit on the number of classes a student could attend, though some Professors may have done so, for practical reasons.

The 1904 memorandum gives the following student numbers, including medical students:

in 1890: 315; in 1893: 418; in 1896: 502.

Professors and lecturers salaries: 1891-2: £7649. 1893-4: £8462

(Totals for each year) 1892-3: £8213 1894-5: £9737

Student Fees: In 1881, Day Classes were held on three days per week; the fee for 1 term was £2, for two terms £3 and a full year £4. The registration fee was £1.1s. Applicants under the age of sixteen had to take a preliminary examination. Evening classes were held once a week, the fee was 5s per term for one hour a week, with a 1s registration fee.

Appendix 4.

Some sources on Waterhouse and the Victoria Building.

. Minutes of the Building Committee, 1887-1893, being the Joint Committee of The Council

and Senate, established in March 1887.

. University College Council, Annual Reports for 1892, 1893, 1894, 1895 and 1896.

. Minutes of the Committee on College Sites, March 1899.

. Principal Rendell’s letters to Alfred Waterhouse and others, November 1889 – 1895;

includes a few from Professor Lodge to Waterhouse and Reginald Bushell, second son of

Christopher; a few from Rendell to Paul Waterhouse, AW’s son and partner from 1890,

the first being in February 1890, when AW was in Spain, recovering from illness.

. List of Donors to the College, as at September 22nd 1891.

. Council pamphlet of April 1901, outlining plans to secede from Victoria University.

. Almanac dated 1902, summing up the early history of the College.

. Memorandum of April 1904, requesting a grant of £20,000.

. Three articles by Principal Rendall, printed in the Liverpool Review, 1892-3.

. Two articles by Adrian Allen, retired librarian, from the University Magazine, Recorder, in

April and October 1980, based on much of the above.

. Article by Michael Cook, in ‘Precinct’, May 1978. This is the ‘Centenary Celebration’

issue, where Cook reviews the events leading to the ‘Town Meeting’ of May 1878. The

issue also has a Waterhouse perspective drawing of the College precinct in 1896 and a

street map of the area in 1868, clearly showing the Asylum and the rail cutting (or perhaps

its intended route?) as well as the Royal Infirmary and the Medical School in Dover Street.

. Alfred Waterhouse, Biography of a Practice, by C Cunningham and P Waterhouse.

. A.Waterhouse, 1830-1905. by C.Cunningham, S.McDonald and S.Maltby. RIBA 1983.

. Liverpool by Joseph Sharples.

. For Advancement of Learning – The University of Liverpool, 1881-1981 by Thomas Kelly.

and Senate, established in March 1887.

. University College Council, Annual Reports for 1892, 1893, 1894, 1895 and 1896.

. Minutes of the Committee on College Sites, March 1899.

. Principal Rendell’s letters to Alfred Waterhouse and others, November 1889 – 1895;

includes a few from Professor Lodge to Waterhouse and Reginald Bushell, second son of

Christopher; a few from Rendell to Paul Waterhouse, AW’s son and partner from 1890,

the first being in February 1890, when AW was in Spain, recovering from illness.

. List of Donors to the College, as at September 22nd 1891.

. Council pamphlet of April 1901, outlining plans to secede from Victoria University.

. Almanac dated 1902, summing up the early history of the College.

. Memorandum of April 1904, requesting a grant of £20,000.

. Three articles by Principal Rendall, printed in the Liverpool Review, 1892-3.

. Two articles by Adrian Allen, retired librarian, from the University Magazine, Recorder, in

April and October 1980, based on much of the above.

. Article by Michael Cook, in ‘Precinct’, May 1978. This is the ‘Centenary Celebration’

issue, where Cook reviews the events leading to the ‘Town Meeting’ of May 1878. The

issue also has a Waterhouse perspective drawing of the College precinct in 1896 and a

street map of the area in 1868, clearly showing the Asylum and the rail cutting (or perhaps

its intended route?) as well as the Royal Infirmary and the Medical School in Dover Street.

. Alfred Waterhouse, Biography of a Practice, by C Cunningham and P Waterhouse.

. A.Waterhouse, 1830-1905. by C.Cunningham, S.McDonald and S.Maltby. RIBA 1983.

. Liverpool by Joseph Sharples.

. For Advancement of Learning – The University of Liverpool, 1881-1981 by Thomas Kelly.

Appendix 5.

Letters from Principal Gerald Rendall to Alfred Waterhouse 1889 – 1892.

It would be tedious, though interesting, to quote from every letter which Rendall wrote, but what is clear is Rendall’s commitment to the project and his desire, shared by the architect, to get the building right. The letters are hand-written and cover all manner of details. We have only have Rendall’s side of the story and it would be fascinating to read Waterhouse’s replies, not only to see how he deals with his client’s many requests and complaints but also the tone he adopts in doing so.

The seventy letters I have read, between November 13th 1889 and December 1892, are only part of the correspondence fired off to New Cavendish Street in London – it is a credit to Waterhouse’s patience and professionalism that he seems to have responded to each letter. I wonder if all his clients wrote to him so often and on so many topics?

(This may well be a hallmark of Waterhouse’s professional manner, for when he was designing Hinderton Hall for Christopher Bushell in 1855, fifty-four letters survive concerning the building of this country house, a far smaller project than The Victoria Building.) The letters in 1891 and 1892 are more frequent and more urgent and cover a huge range of issues including:

Lavatories and Sanitary provision.

Slow building progress, including lack of ironwork and terracotta.

The route for the water pipes.

Design of the staircase at second floor level and the third floor rooms.

Lighting and electricity provision.

Gas lighting – where and how many fittings.

Office and student furniture, especially surfaces.

Number and location of clocks.

Inscription on the Jubilee Tower (in Latin!)

Slow building progress, including lack of ironwork and terracotta.

The route for the water pipes.

Design of the staircase at second floor level and the third floor rooms.

Lighting and electricity provision.

Gas lighting – where and how many fittings.

Office and student furniture, especially surfaces.

Number and location of clocks.

Inscription on the Jubilee Tower (in Latin!)

Some particular topics are worth highlighting:

. Rendall insists on separate cubicles in the male lavatories.

. He writes about the required angle for seating on the benches in the Ladies Common Room,

based on the comfort of his own furniture at home!

. In December 1892, he is very concerned about progress, as the Council have invited the

Prince of Wales to open the building. “I shrink from the risk of the fiasco involved (if the

building is not ready)”. It was not!

. “I have hit on an idea to permit exams in the Arts Theatre”. (by removing sections of seating

and setting out tables and chairs)

. “In the Theatre, the platforms must be continuous when put together”. Rendell then draws a

sketch of the shape of the moulding on the edges of the platforms to ensure this.

. Desks need ink-pots and pen-trays.

. Rendall does not want gas connected to the fire of the Ladies Common Room.

. 15/3/92: Brown and Backhouse have varnished some desks, not ebonized, as required.

. 15/6/92: Brown and Backhouse have ebonized some furniture, not polished, as required.

. On the 8th September 1892, Rendall writes that term starts on October 3rd and he must have

the building by then.

. On the 28th September 1892, he writes that Brown and Backhouse are VERY slow to

clean up and get the building ready; he fears he will have to postpone classes and lectures.

. He writes about the required angle for seating on the benches in the Ladies Common Room,

based on the comfort of his own furniture at home!

. In December 1892, he is very concerned about progress, as the Council have invited the

Prince of Wales to open the building. “I shrink from the risk of the fiasco involved (if the

building is not ready)”. It was not!

. “I have hit on an idea to permit exams in the Arts Theatre”. (by removing sections of seating

and setting out tables and chairs)

. “In the Theatre, the platforms must be continuous when put together”. Rendell then draws a

sketch of the shape of the moulding on the edges of the platforms to ensure this.

. Desks need ink-pots and pen-trays.

. Rendall does not want gas connected to the fire of the Ladies Common Room.

. 15/3/92: Brown and Backhouse have varnished some desks, not ebonized, as required.

. 15/6/92: Brown and Backhouse have ebonized some furniture, not polished, as required.

. On the 8th September 1892, Rendall writes that term starts on October 3rd and he must have

the building by then.

. On the 28th September 1892, he writes that Brown and Backhouse are VERY slow to

clean up and get the building ready; he fears he will have to postpone classes and lectures.

The opening was in fact postponed from June to December, when The Earl Spencer was present at the opening ceremony, and the Victoria Building substantially completed.

Appendix 6

Benefactors and donations to Liverpool University College and the Victoria Building, 1878 – 1905

Without question, the College owed much to the generosity of Liverpool benefactors, merchants, bankers, industrialists, philanthropists, aristocrats, ship-owners and those committed to the development of the education of young people. The Council Reports and Donor List of 1891 detail those who contributed, as does, for example, the pamphlet produced on the opening of the Chemistry Laboratories, where four pages of donors are listed. It is not always possible to say when a donation was made or what for – often it was for the general building fund or a professorial ‘Chair’ or a particular department or subject, sometimes for a specific building. There was also a ‘Sustentation Fund’, which I assume was set up to sustain the future financial position of the College, as it developed. The examples below are taken from various sources and attest to the generosity of wealthy Liverpool citizens. Some made many small donations; others, a few but large donations. So often, the same names keep appearing in times of financial crisis: Holt, Rathbone, Tate, Derby, Hartley.

After the first ‘Town Hall’ Meeting in 1878, gifts of between £20,000 and £8,000 were received by 1881, from various donors. Subsequent gifts and endowments included:

After the first ‘Town Hall’ Meeting in 1878, gifts of between £20,000 and £8,000 were received by 1881, from various donors. Subsequent gifts and endowments included:

W, SG and PH Rathbone £10,000 (Modern Literature)

Col. AH Brown, Mr W Crosfield, Mr J Barrow £10,000 (Classics and Ancient History)

Mrs Grant, sister of Lloyd Rayner * £10,000 (Chemistry)

Trustees of Roger Lyon Jones Fund £10,000 (Physics)

The 15th Earl of Derby £10,000 (Natural History)

TL Cope and M Guthrie ** £21,000 (Chemistry Labs)

S Smith and A Balfour *** ?

The Roscoe Family and Unitarians (47)?(Art)

1883 H Tate £5,000

Rev J. Thom; G.Holt; W, SG, T

and B. Rathbone**** £10,000 (for Medical Degrees and Courses)

1884 Town Meeting voted to join The

Victoria University and raised.. £30,000 (History and Classics Departments)

1885 Bushell Scholarship Fund £1,000

1887 Sir A B Walker £24,000 (Engineering Laboratories)

T Harrison £10,000 (Chair in Engineering)

T Harrison £10,000 (Chair in Engineering)

1888 H Tate £16,000 (+ £9,000) Library and books

1892 The 15th Earl of Derby £2,000

Queen Victoria £2,000 (Law Faculty and Professorship)

Liverpool Law Society £2,000 (as above)

Rev SH Thompson-Yates £15,000 (Physiology and Pathology Labs

G Holt £10,000 (Physiology Chair)

G Holt £5,000 (maintain and develop Phys/Path Labs)

W Hartley £1,100 (Clock and Bells for Jubilee Tower)

Queen Victoria £2,000 (Law Faculty and Professorship)

Liverpool Law Society £2,000 (as above)

Rev SH Thompson-Yates £15,000 (Physiology and Pathology Labs

G Holt £10,000 (Physiology Chair)

G Holt £5,000 (maintain and develop Phys/Path Labs)

W Hartley £1,100 (Clock and Bells for Jubilee Tower)

1893 H Tate £5,500 (books for various Departments)

The 16th Earl of Derby £2,000 (scholarships and exhibitions)

The 16th Earl of Derby £2,000 (scholarships and exhibitions)

1894 FH Gossage, TS Timmis £7,000 (Chemistry labs, in mem: W.Gossage)

H Gaskell £5,000 + fundraising of £10,000. (Botany)

G Holt £10,000 (Pathology Chair)

G Holt £5,000 (to develop and maintain Pathology lab)

H Gaskell £5,000 + fundraising of £10,000. (Botany)

G Holt £10,000 (Pathology Chair)

G Holt £5,000 (to develop and maintain Pathology lab)

1895 Gossage,Timmis,Brunner,Muspratt £9,000 (to develop and maintain Chem Labs)

W Hartley ? (for new Physics classroom)

1905 G Holt Fund £4,000 (Zoology Museum)

* Rayner was a merchant. Waterhouse had built a house for him in 1868, Mossley Park in Park Avenue, Mossley Hill, now part of Mossley Hill Hospital.

** Guthrie, a silk mercer, lived in Parkfield Road, Aigburth. He was also Secretary of the fund-raising Committee for the Chemistry Labs. Cope was a tobacco manufacturer.

*** Both renowned philanthropists in Liverpool. See Balfour’s statue in St John’s Gardens, by Bruce Joy (who also sculpted Christopher Bushell in The Victoria Building.) He founded the Seamens’ Orphanage in Newsham Park and would therefore have known Waterhouse, the architect of the building (1870).

**** This funding came about because The Victoria University announced in 1883 that it was proposing to confer Medical Degrees. The College Council thought this posed a serious threat to the viability of the Liverpool Medical School, with which the College was working closely. Indeed during the next year the Medical School became the Medical Faculty of the University College in June 1884; it was shortly after this step that the College joined the Victoria University. Part of this funding was also used to broaden the range of subjects taught at the College, in order to qualify for entry into Victoria University

Many of these men and women are recognized for their generosity by a statue (Balfour, Bushell) or a plaque (Holt, Jones); or by the building bearing their name (Tate, Walker, Harrison, Holt, Derby, Rathbone, Thompson-Yates, Gossage, Hartley, Muspratt, Rendall, Waterhouse); or by a scholarship in their name (Bushell) or a Professorial Chair (Grant, Roscoe, Derby). Others have not been so recognized but played their part (for example, Edward Lawrence was Chairman of the College Council from 1881 to 1903). Edmund Muspratt, a chemical manufacturer, served on the College Council as Vice-Chairman from 1888 and was President of the University Council from 1903-1909.

Yet this list does no justice to those of lesser means, who contributed far smaller amounts to the University in the 1880s and 1890s. Yet their gifts totalled several hundred thousand and were also vital in setting up the College on Brownlow Hill.

The Donor List published in September 1891 is interesting. The donors number at least a thousand, with many donating more than once between 1881 and 1891. Some twelve funds were open, including Buildings, Departments, Scholarships and Professorships. Fifty-six donors gave single donations of one thousand pounds or more. The most generous individuals were Andrew Walker, Henry Tate, and George Holt, while the most generous family were the Rathbones – six are named as well as a family company. Others gave at least one thousand pounds spread over several donations. The fifty-six are:

Balfour Williamson and Co W Gossage and Sons J Rankin MP

W Battenbury SB Guion B Rathbone

JJ Bibby T Harrison PH Rathbone

JC Bingham and Co W Hartley RR Rathbone

A Booth Miss A Holt SG Rathbone

T and J Brocklebank G Holt T Rathbone

Col AH Brown Mrs E James W Rathbone

J Clifton Brown D Jardine M Rathbone and Co

J Brunner W Litherland J Rew

C Bushell Liverpool Law Society W Sandbach

The 15th Earl of Derby Liverpool City Council W Sinclair

The 16th Earl of Derby L Mond S Smith MP

J Dixon Sir R Moon Ross T Smyth and Co

HW Gair JP Moss, James and Co H Tate

CB Gamble EK Muspratt JH Thom

JC Gamble and Son Mrs S Muspratt SH Thompson-Yates

H Gaskell JP TW Oakshott AB Walker

Gaskell, Deacon and Co J Pickup

R Gee M Ranger Mrs Grant

W Battenbury SB Guion B Rathbone

JJ Bibby T Harrison PH Rathbone

JC Bingham and Co W Hartley RR Rathbone

A Booth Miss A Holt SG Rathbone

T and J Brocklebank G Holt T Rathbone

Col AH Brown Mrs E James W Rathbone

J Clifton Brown D Jardine M Rathbone and Co

J Brunner W Litherland J Rew

C Bushell Liverpool Law Society W Sandbach

The 15th Earl of Derby Liverpool City Council W Sinclair

The 16th Earl of Derby L Mond S Smith MP

J Dixon Sir R Moon Ross T Smyth and Co

HW Gair JP Moss, James and Co H Tate

CB Gamble EK Muspratt JH Thom

JC Gamble and Son Mrs S Muspratt SH Thompson-Yates

H Gaskell JP TW Oakshott AB Walker

Gaskell, Deacon and Co J Pickup

R Gee M Ranger Mrs Grant

As far as I can ascertain, the most generous benefactors between 1881 and 1895 were:

George Holt who gave c.£40,000; Henry Tate, £35,000; and Andrew Barclay Walker, £24,000. The Revd Thompson-Yates gave either £30,000 or £15,000 depending on which document is used. (The Harrisons and Hughes gave £40,000 for engineering in 1912)

Interestingly, Professor John Belchem in his book on Liverpool 800 states that John Rankin, MP and industrialist, was the most generous benefactor to the College. He may mean the most generous Scot! I’ll pursue this one.....

Appendix 7.

Some Inscriptions in and on the Victoria Building.

“Victoriae reginae Dei gratia L Annos Feliciter Regnanti Cives Posuerunt”

“For Victoria, Queen by the grace of God, in commemoration of fifty years of happy reign;

erected by the citizens (On the Jubilee Clock Tower)

“Ring out the old, Ring in the new, Ring out the false, Ring in the true, Ring in the Christ that

is to be."

is to be."

From Tennyson’s poem: In Memoriam (On the five bells in the Jubilee Tower)

“For the advancement of learning and ennoblement of life the Victoria Building was raised by the Men of Liverpool in the Year of Our Lord 1892.”

(Inscription on the Brownlow Hill facade of the Building)

(Inscription on the Brownlow Hill facade of the Building)

“Regnare est Servire” To rule is to serve.

(On the fire surround in Rendall’s study)

“It is the function of the King to do good and be slandered for it”

Translation of a Greek quotation on another fire surround in Rendall’s rooms)

Translation of a Greek quotation on another fire surround in Rendall’s rooms)

“Quaecunquae vera, pudica, amabilia”. Whatever is true, pure, and lovely.

From St Paul’s Epistle to The Philippians Ch4 v8

(On the fire surround in the Women’s Common Room)

From St Paul’s Epistle to The Philippians Ch4 v8

(On the fire surround in the Women’s Common Room)

Appendix 8

Appendix 9.

BURMANTOFTS: The Company was called Willcocks and Co when it was founded in 1845 to extract the clay from the shafts of The Rock Colliery in the Burmantofts area of Leeds (east of the city centre). The firm specialised in architectural salt-glazed bricks, terracotta, ceramic tiles and pottery. By the 1880s the firm was a serious rival to Doulton. The firm took the name Burmantofts in about 1879, until amalgamating with others to form the Leeds Fireclay Company in 1889. The Company closed in 1957.

(Cunningham and Waterhouse cite Alfred Waterhouse’s first use of the firm in 1879 on his Head-quarters building for the Prudential Assurance Company in London)

Before using Burmantofts, Waterhouse usually used Craven, Dunnill or Godwin for tiles and faience. He continued to use all three in the 1880s and 1890s.

Appendix 10.

The Carrara marble statue of Christopher Bushell by Albert Bruce-Joy was unveiled on January 30th 1885 to recognize his contributions to education in Liverpool over many years and was temporarily housed in the ‘Free Library’ in William Brown Street until the Victoria Building was opened. It was first placed in the ‘apse’ of the hall, moved in the late 1960s to Abercromby Square, then placed in store in the mid-1970s, before returning to the Victoria Building in 1986, when it was restored. Further partial restoration took place in 2008.

The University of Liverpool was founded in 1881. We are aware that, as a civic institution created in one of the centres of Britain’s eighteenth and nineteenth century economy, and a seaport, the legacies of slavery and colonialism form part of our story. We are about to enter into a period of reflection through which we will consider, in consultation with our members and local communities, how we might appropriately recognise this.