Dental Collection Further Information

In the Tate Hall museum you can visit our internationally important display of dentistry. The exhibition is an exploration of the history of dentistry and includes dental equipment and even dentures made from human teeth!

You can also take a peek into a Victorian dentist’s room

Exploring the Exhibition - Some Highlights

Early Dentures of Ivory

The first European dentures were carved from solid blocks of hippo, walrus or elephant ivory. Teeth made from walrus ivory were known as ‘seahorse teeth’. Tiny versions of the ivory dentures were carved by apprentices, who must have needed a lot of practice before they were allowed to risk wasting larger blocks of ivory. Ivory was often uncomfortable and could not be held in place very easily. Sometimes chamois leather was attached, to cushion the gums.

Teeth with a tale to tell…

This partial upper and lower denture of cast aluminium on the left was made by a dental mechanic during WWII. Whilst a prisoner of war in the infamous Changi Prison Camp in Singapore. The full upper and lower denture of vulcanite dentures on the right are from a patient aged 92 years. The vulcanisation of natural rubber with sulphur was discovered by Charles Goodyear in about 1839.

Dentures held in by coiled springs required considerable practice to put in and take out and were almost impossible to thoroughly clean. One textbook admitted that they induced “a disposition to paralysis of the muscles of the lower jaws” still they did at least enable the wearer to hold a conversation without them falling out. In the 1860s and 70s false teeth advertisements proclaimed “atmospheric pressure” as a marvellous new invention for holding in false teeth. Unfortunately, the intense suction could (and frequently did) seriously injure the roof of the mouth.

Waterloo Teeth 1700’s and 1800’s

Although dentures made from human teeth came to be named after the Battle of Waterloo in 1815, they were already popular in the 1700s. When it was realised that the teeth of young, healthy soldiers were of much higher quality - with less decay and disease – it started a new and very profitable trade in battlefield teeth. As late as the 1860s, England imported more than 50 barrels of teeth from the battlefields of the American Civil War.

At first, the teeth were obtained from executed prisoners and unidentified paupers, but grave robbers also provided a ready supply. The very poor were also tempted to sell their healthy teeth.

Instruments and Extraction

The first record of the use of a pelican was in 1363, and by the 1500s, it was the main tool used for tooth extraction. Even when used by an expert, it could result in serious damage to surrounding tissue. This example dates from the early 1700s.

Tooth keys were introduced in the early 1700s.Their use was still very unpleasant, but they were less damaging than pelicans. They were modelled after a door key and were at first straight in their design with a claw on the end. The key would be inserted into the mouth horizontally and the claw tightened around the diseased tooth. It would then be rotated at the handle to loosen the tooth. This would often caused pressure on the healthy tooth next to the tooth being extracted and cause damage. By 1795, extra curves were added in the shaft, helping to reduce damage to the jaw and the adjacent teeth. The tooth key was still being used in Britain until about 1910, but by the early 1900s, they were quickly replaced by the forceps (seen on the right). They had jaws designed to fit the size of tooth to be extracted, and had handled curved to fit the hand.

Not Forgetting Toothache!

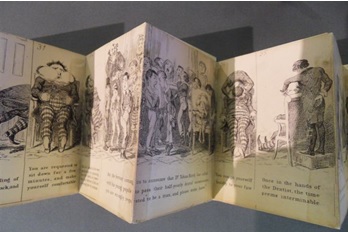

This was published in 1849, The Toothache – ‘imagined by Horace Mayhew and realised by George Cruikshank’ – is a long comic strip that folds out accordion-style and tells the story of a hapless gentleman who wrestles with his fear of extraction and used various useless remedies until the pain gets the better of him and he submits to the dentist.