The Wartime Watch

Posted on: 18 March 2022 by Kim Fisher, VG&M Visitor Services in 2022

Our clock tower played an important role during World War Two and this blog takes a closer look at what happened 81 years ago, in March 1941.

“When war came, they (the University Auxiliary Fire Service) were trained and competent…they took the leading part in its protection; they drilled the Fireguards and set them an example of courage and coolness. They played a magnificent part, the record of which should never be forgotten.” – University Registrar Stanley Dumbell

The Wartime Watch

During WWII, the Jubilee Clock Tower in the Victoria Building was used as the main observation post for fire watching as it was a high vantage point at the top of Brownlow Hill. Sighting instruments were installed on the balcony near the clock and charts were in the clock tower room. The watch crew were in contact with the fire headquarters in Hatton Garden as well as an auxiliary fire crew stationed next door in the Ashton Building.

Photograph - The Victoria Building & Jubilee Clock Tower, circa 1930.

The firewatchers were student and staff volunteers with four people on duty each night and working a six-night rota. When the sirens sounded, two firewatchers would ascend the clock tower and report the location of the fires. This crew became the Auxiliary Fire Service from 1939 which was eventually absorbed into the National Fire Service in 1941.

“High above the city, as if on Olympus, we enjoyed a wholly false feeling of immunity and a splendid view. Some nights, especially during the March and May raids of 1941 we witnessed some spectacular disasters…we would ascend the stairs to the tower intoning with vigour ‘Those swine, those foul swine.’” – Frank William Wallbank.

Photograph - Views from the Victoria Building clock tower today, looking down towards the river and Liver Building.

Memories of Abercromby Square

The firewatchers reported vivid memories of the Victoria Building clock tower rocking when high explosives hit Lewis’s and T.J Hughes stores, as well as watching the cross on the dome of St Catherine’s Church in Abercromby Square falling into the flames.

Image - This watercolour painting of Abercromby Square and St Catherine’s Church is by Allan Peel Tankard in 1952. Number 18 is depicted on the left of the church, two doors down.

Mr. J.R. Gell lived at number 18 with his Grandmother shortly before the war and wrote about the destruction of the church in a memoir:

“I went upstairs with my grandmother in the main hallway where I learned the church had been bombed and was ablaze with fire from end to end…I was taken into the back yard by an adult to let me see the flames which were shooting skyward from the church. The damage must have been confined to the inside as the exterior showed no sign of fire including the tall double doors at the front...The bombing of the church had to be an incendiary bomb as at no time did I hear any explosions – a sound that was not mistaken.”

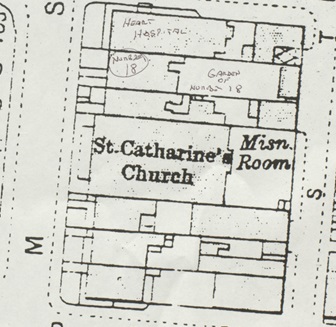

Image – A Plan of Abercromby Square from recollections of Mr J.R Gell and the house he grew up in which was next to St Catherine’s Church. D1800 University Special Collections and Archives.

Due to dry rot and the damage during the war, the whole of the east side of Abercromby Square was demolished in 1966 and is now the site of the University’s Sydney Jones Library.

Engineering Explosions

Full illustration from Michael White showing the Victoria Building with a parachute bomb drifting past the tower.

Two months before the devastation of the Liverpool Blitz, the University of Liverpool campus suffered a direct hit during the night of the 12-13th March 1941.

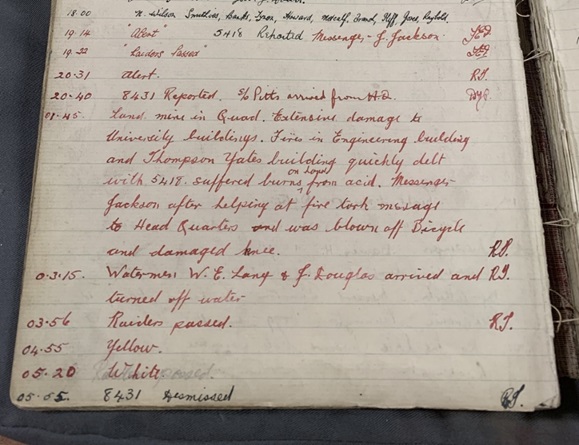

According to the tower log, at 01:45 am a parachute mine, or landmine as they were called by the Civil Defense, hit the University quadrangle and damaged the Harrison Hughes engineering building. The fires in the Harrison Hughes and Thompson Yates Buildings were quickly dealt with and although there was no loss of life, the firewatcher’s logbook shows that two of the wardens were injured - one with an acid burn to the hand and messenger J. Jackson was blown off his bicycle injuring his knee.

Bill Hogg was the Quad sweeper who saw the mine drifting down and ran to the fire watcher’s recreation room and sought refuge under the billiard table.

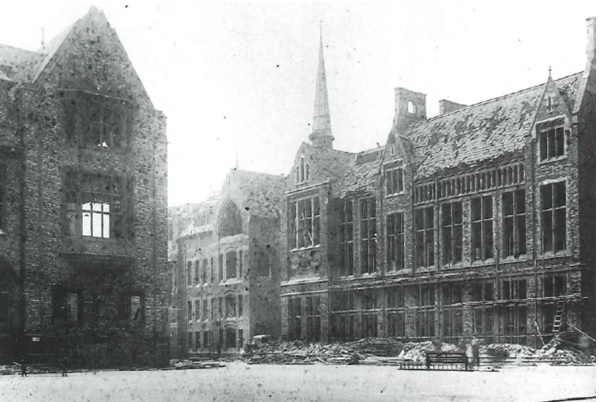

Photograph - The damage to the Harrison Hughes and Ashton buildings in the quadrangle, March 1941. The Victoria Building is situated just behind and blocked from view.

By 4:00 am the raiders had passed, but the watchers were following the ‘yellow’ Air Raid Warning Code and stayed by their post until the ‘white’ signal was recorded at 05:20 am. An ‘all clear’ siren would then alert the public that the danger had passed.

Photograph - Firewatchers logbook from 12-13th March 1941, University of Liverpool Special Collections and Archives.

Another record comes from the Head of the Metallurgy department Dr Stanley John Kennett:

“Our last remaining research student was on the tower during an otherwise uneventful night when a parachute mine drifted past the tower and came to rest at the foot of the Harrison Hughes Engineering Building. The disbelief of the squad below when this event was reported on the intercom saved their lives, since when they eventually decided to investigate they were only approaching the door leading out to the quadrangle when the mine exploded, destroying that corner of the Laboratories.”

Photograph- A closer photograph of the damage to the Harrison Hughes Laboratory with a small section of the Victoria Building behind with damaged and missing windows.

Mechanical engineering lecturer Norman Geoffrey Calvert was also on duty on the night the parachute bomb dropped in the quadrangle and he felt the Victoria tower rock. Bits of the aluminium casing from the bomb were later melted down by Calvert and made into a sugar bowl with the inscription “Blast Hitler” which was then presented to Professor G.E. Scholes who had led the University watch during the war.

Damage to The Victoria Building

“The blast removed the roofs of the medical school and Thompson Yates laboratory which lay nearest and blew out doors and windows in the surrounding buildings.” University Registrar Stanley Dumbell.

We can’t be sure of the extent of damage to the Victoria Building but a letter written in 1941 by the Professor of Geography Percy Roxby details that the windows, doors and heating in the Victoria Building were destroyed, as the Harrison Hughes boiler had originally supplied our heating.

Photograph - The corner of the Harrison Hughes building (left) opposite the Whelan Building and Thompson Yates Laboratory after the blast in March 1941.

Repairs were carried out rapidly so that university life could continue unaffected and Calvert mentions in a letter that temporary repairs to the windows were undertaken by his team. The window repairs were made from plastic celluloid reinforced with a plastic net and wooden frames and were later replaced by contractors.

The windows in the Victoria Building which were designed by Alfred Waterhouse originally had stained glass which can be seen in the image below.

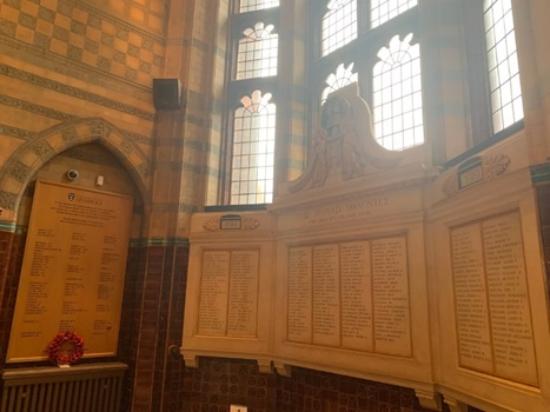

Photograph - The First World War Memorial and original stained-glass windows in the Victoria Building, circa 1930s.

The windows on the north side of the building which all face the quadrangle are completely different to the south side of the building and so we can assume that these were replaced shortly after the war, but not in the same style that Waterhouse had originally designed.

Photograph - Window examples from the south side of the Victoria Building showing what the colours and patterns of the other side of the building may have resembled before the war.

During the May Blitz of 1941, Merseyside was heavily raided on seven successive nights and bombs fell in Abercromby Square, Brownlow Street and also in Ashton Street where the Victoria Building and its clock tower stood watch over the city. Although damage was widespread, thankfully there was no direct hit and the University did not stop its teaching or close its doors.

Memorials and Memories

Thankfully there was no loss of life on campus during the war but our War Memorials list the staff and students that were lost during both World Wars and the VG&M holds a service on Remembrance Day each year.

Photograph - War Memorials at the VG&M and the replacement windows on this side of the building.

It is thanks to the wartime watch stationed in the Victoria Building clock tower that many fires across the city were quickly dealt with and our building has another important, yet lesser known connection to the city’s history.

It is also thanks to the memoirs held in the University Special Collections and Archives and recollections from university books that we can piece these accounts together and understand our University history.

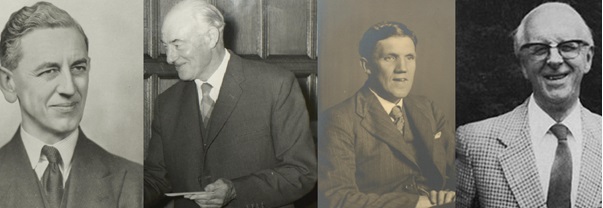

Photographs – From left to right – Dr Stanley John Kennett, Mr Stanley Dumbbell, Professor Percy Roxby and Professor Frank William Wallbank who all served as a members of the tower watch during the war.

With thanks to the University of Liverpool Special Collections and Archives

Keywords: World War II, Victoria Building, Clock Tower, Firewatchers, Parachute Bomb, Abercromby Square, University of Liverpool, Liverpool Blitz, St Catherine's Church.