The Leaning Tower of Liverpool

Posted on: 15 November 2022 by Kim Fisher, VG&M Visitor Services in 2022

Our iconic clock tower is part of the university’s flagship building and helps our visitors to locate us. We can be heard across campus every 15 minutes as our bells chime and mark the passing of time and in this blog we find out more about the clock, tower and bells on the 130th anniversary of the Jubilee Clock Tower’s opening ceremony.

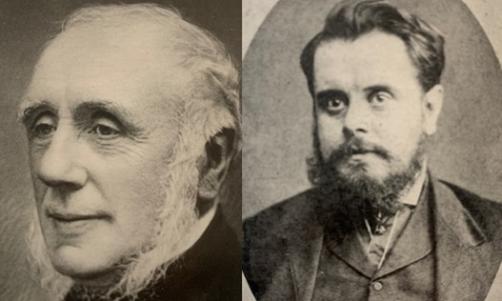

Left – William Potts, founder of clockmakers Potts of Leeds, Right – William’s son Robert Potts.

The Jubilee Clock Tower Opening Ceremony

During the clock tower opening ceremony on 15th November 1892, William Rathbone VI, the President of University College Liverpool, addressed the audience gathered in the Arts Lecture Theatre. He stated that faith did not only remove mountains, it built colleges and this particular college was a perfect example because what had started off as a small group of men contributing £2,500, suddenly became £250,000 from the citizens of Liverpool.

The last act of faith had come with the Jubilee Clock Tower because although £4000 had been given by the Jubilee Committee, that sum was only just about enough to cover the tower construction and there was nothing left for the clock or bells. The tower construction went ahead regardless and soon a donor stepped forwards and offered to supply the clock and bells at a cost of £1,133.

Jam manufacturer William Hartley had read about the appeals for donations and that the college required a clock and chimes but had no money to pay for it. It had always been his greatest joy to help forward educational, philanthropic and religious movements for the city of Liverpool and he expressed the hope that the clock would be for the benefit of everyone connected to the university and to the citizens of Liverpool for generations to come.

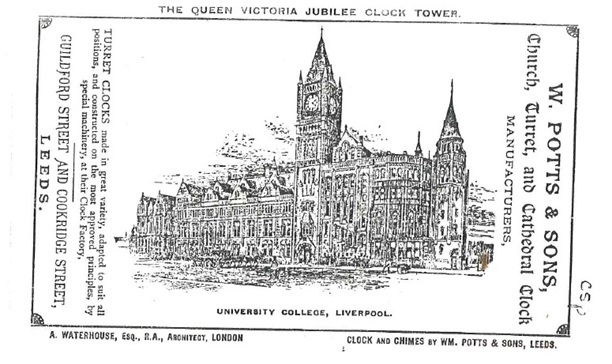

Potts of Leeds were the chosen clockmakers commissioned for the job and Hartley commissioned four Potts of Leeds clocks during his lifetime – one for his factory in Aintree, one for the Victoria Building, one for Colne Town Hall and one for the Methodist College in Manchester.

Jam manufacturer and University College Liverpool donor, William Hartley.

During the ceremony, the setting in motion of the clock was undertaken by Hartley in front of many of the college professors and local dignitaries which also included William Potts’ son Robert. The company gathered in the Tate Library; which at that point was devoid of any books as the building had not yet opened publicly to the student body and was still having the last finishing touches made. Shortly before 5pm Mr Hartley ascended the tower steps to set the clock in motion so that everyone would be able to hear the clock and bell strike the hour.

Architectural Inspiration

Proposed Clock tower for C Turner, designed by Waterhouse circa 1881.

This clock tower design by Alfred Waterhouse appeared in ‘The Architect’ in 1881. It was the proposed design to be erected in memory of Liverpool MP Charles Turner who died in 1875. The design was presumably abandoned after Turner’s son died in 1880 and his widow wanted something built in memory of both of them. Subsequently, the Turner Memorial Home was built in 1884 and was founded for the care of sick and disadvantaged men.

Waterhouse would’ve kept all of his architectural plans and drawings and although this tower was never constructed it is possible that elements of its design were used for the Victoria Building’s Jubilee Tower.

Proposed design for the Victoria Building circa 1887, without the iconic clock.

An early plan from 1887 shows one of Waterhouse’s first designs for the Victoria Building and there are similarities between this design and the 1881 clock tower illustration, especially when looking at the roof of both structures. In the very same year, the Jubilee Memorial Committee approached the college to give them £4,5000 towards the construction of the clock tower as long as a few stipulations were met. Changes were made to this original drawing to include a clock with chimes, jubilee inscriptions and royal emblems.

Proposed design for the Victoria Building circa 1887, without the iconic clock.

Although we can’t be certain that this earlier design was utilised by Waterhouse for the Victoria Building, there is a striking similarity.

The Clocks

The cast iron clock dials and mosaic clock on the exterior of the building were designed by Alfred Waterhouse who designed the rest of the building. Interestingly, the Turner Memorial Home also has a mosaic clock designed by Waterhouse and there are only 6 of these clocks in the UK.

Turner Memorial Home mosaic clock, designed by Alffed Waterhouse

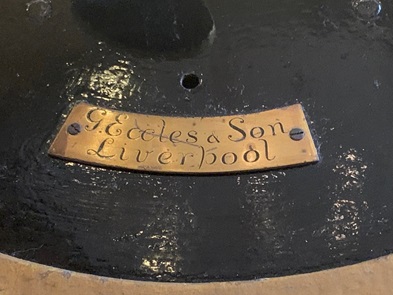

Today, only the fireplace clock on the ground floor, Charles W. Jones clock outside the Leggate and the exterior tower clocks are still in existence. A brass plaque on the ground floor fireplace clock shows that it was made by local clock makers George Eccles & Sons who had a business at 29 Ranelagh Street, Liverpool but we can’t be certain if they made all of the interior clocks in the building.

Brass plate on ground floor fireplace clock, showing clock makers G Eccles & Son, Liverpool.

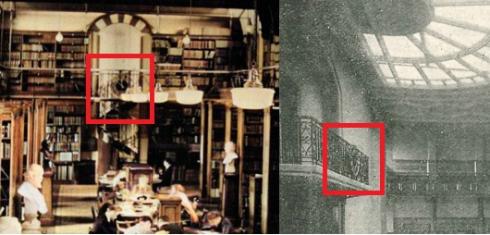

One clock dial was positioned in the Library by the spiral staircase and it was connected via electricity to the tower clock. Two other clocks on the balcony in the Lecture Theatre and the Grand Entrance Hall were all similarly arranged so that they would be keeping time with each other. The hands on the main tower clock dials moved as the clock drive turned and the other three clocks were connected and driven by electric impulses every minute. This arrangement was set by the clock makers and Professor Campbell Brown from Chemistry advised on the synchronisation.

Left - The Library clock can be seen above the spiral staircase, Right – The Leggate Theatre clock is just about visible & positioned on the iron balcony rail.

The tower clock was made by Leeds clockmakers William Potts & Sons, costing around £630. It is based on Alfred Waterhouse’s design of four large mosaic dials, each eleven foot in diameter. The “Going Train” or main gear of the clock could go eight days once wound and the “Striking Train” would have to be wound every two days.

A close up of the clock tower mosaic designed by Alfred Waterhouse

There are several articles in ‘The Sphinx’, the student magazine which refer to our clock. In one article from 1892 called ‘Suggestions for a college song,’ some of the building’s features have been put into a humorous song by one of the students themselves, stating the following:

“…There's the Tower of patent red brick,

suggestive of waterworks strong…

It commemorates Jubilee day,

There's the clock electricity primes.

With its most unaccountable way,

of jumping five minutes, sometimes...”

Almost a year after the building opened, another humorous student article commented that the Jubilee Clock Tower wasn’t straight and that the college could now boast of a ‘Leaning Tower of Liverpool’. They continued that the clock was always running slow and the porter was constantly having to adjust the time and yet it always gave the students amusement to watch the clock jumping in the Grand Entrance Hall.

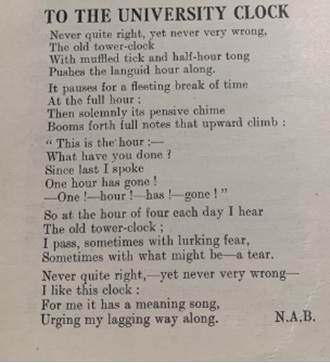

A poem from the mid-1920s comments on how the slow clock and its chimes helped to remind students that time was passing them by and prompted them to think whether they had been productive since the previous hours had chimed, urging them towards study. You can read this part of the poem aloud to the melody of the clock tower chimes, especially at 4:00pm:

‘This is the hour,

What have you done?

Since last I spoke,

One hour has gone.”

Another ode to our clock from The Sphinx Student Magazine, 1926.

In 1967 the automatic winder was updated by William Potts & Sons, and eliminated the need to hand wind the clock. Prior to this conversion, a porter would have to ascend the clock tower every two days to wind the clock and so it was a helpful addition to the staff working in the Victoria Building to have the electrical conversion installed. The Potts & Sons company amalgamated with Smith of Derby in 1935 and each year the tower clock has an annual service which is now completed by Smith of Derby.

The Jubilee Clock Tower mechanism

The Jubilee Bells

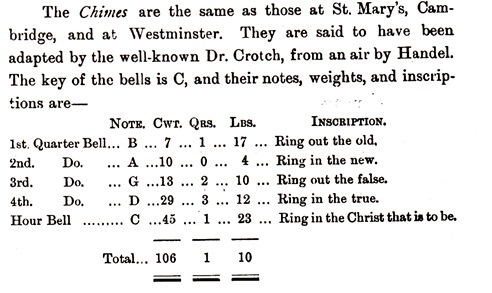

The bells were cast by Taylors of Loughborough and cost around £350 and each have William Hartley’s name inscribed on them. They chime at each quarter of the hour, known as a Westminster Quarter which consists of the notes E C D and G in various combinations. The largest bell weighs 27cwt which is around 1.35 tons or the weight of an adult hippopotamus and the other bells decrease in size to 14cwt (0.7 tons), 10cwt (0.5 tons) and 8cwt (0.4 tons) respectively.

This photograph taken in 2021 shows the word ‘Ring’ and part of the inscription of Tennyson’s poem

Each of the bells is also inscribed with lines from Tennyson’s ‘In Memoriam’ and you can hear the chimes and see the clock mechanism in this video.

From the Sphinx Magazine, 1892, Volume 1 on p 67 - 68 written by Mr Reginald Bushell.

The World’s First Radio Message

In 1897, the clock tower was also used by physics Professor Oliver Lodge to send the world’s first long distance radio message in Morse Code to his assistant on the roof of Lewis’s store which was half a mile away in the city centre. He often sent radio signals to his home from the clock tower which caused complaints as it set off local telephones. He had been working on radio wave transmissions since 1880 and was annoyed that Marconi was sensationalised in the press but his own work had been ignored.

Professor Sir Oliver Lodge.

The Jubilee Clock Tower also played a pivotal role during the Second World War and you can find out more in our other historical blog entitled ‘The Wartime Watch’.

To this day, we hear of many stories of local residents who have used our clock and its bells as their own personal alarm clock and so William Hartley’s wishes were granted as the citizens of Liverpool still cherish the clock tower today, 130 years after it was first officially set in motion.

The stunning views across the city showing the Jubilee CLock Tower in 2022 during the Tate roof renovations.

Keywords: Potts of Leeds, Victoria Building, Jubilee Clock Tower, Alfred Waterhouse, University of Liverpool, University College Liverpool.