Bernard Meninsky: From Ukraine to Liverpool

Posted on: 9 May 2023 by Amanda Draper, Curator of Art and Exhibitions in 2023 in 2023

Our thoughts are with Ukraine as we enter into Eurovision celebrations in Liverpool. So here is the poignant story of Ukrainian-born Bernard Meninsky whose life as an artist began in this city.

Bernard Meninsky c.1926 (image courtesy of Wiki Creative Commons)

Ukraine to Liverpool

Meninsky was born in the city of Konotop in the North Eastern region of Ukraine in 1891. His family were Jewish and his father worked as a tailor. Almost immediately after Meninsky’s birth, the family moved to Liverpool and settled here permanently. He was just six weeks old. He was later to attend St Simon’s School in the city but left aged 11 to work as an errand boy, although he continued to study art at evening classes. In 1906, aged 15, Meninsky won a scholarship to study at Liverpool School of Art which he supplemented with courses at the Royal College of Art in London. Winning a travel scholarship, he then studied at the prestigious Académie Julian in Paris. He returned to Liverpool and was awarded the King’s Medal on conclusion of his studies there. Meninsky finished his formal art training with a year’s scholarship at the Slade School of Art in London. At this point he had been a highly successful student and had a promising career ahead.

Bernard Meninsky: Two Women and a Child, 1913 (coloured pencil on paper). Collection of the Ben Uri Gallery

The Emerging Artist

In 1913, Meninsky started his career in Florence, Italy, teaching at a newly opened art school there, but fell out with its Head and returned to London as a tutor at the Central School of Arts and Crafts. Around the same time, he was starting to gain recognition as a professional artist. He joined the newly-formed London School of artists including Mark Gertler, Wyndham Lewis and William Roberts, then exhibited four of his works in the ‘Jewish section’ of a large exhibition at the Whitechapel Art Gallery alongside David Bomberg and Jacob Epstein. Life was looking positive, but it was soon to change for everybody.

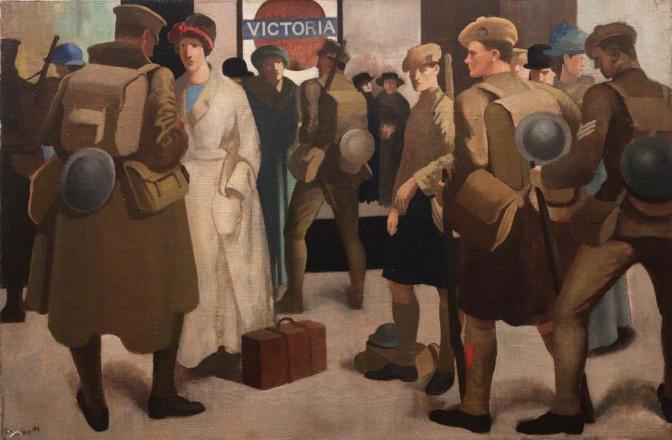

Bernard Meninsky: Victoria Station, District Railway, 1918 (oil on canvas). Collection of the Imperial War Museum

World War One

On the outbreak of war, Meninsky enlisted in the 42nd Battalion, Royal Fusiliers, serving as a clerk. In 1917 he married Margaret O’Connor and a year later they welcomed their first child, David. However, Meninsky was discharged from active service in 1918 due to ‘neurasthenia’, otherwise termed a nervous breakdown. He was appointed as an official war artist to capture scenes of London life, as shown above, but in many ways his mental health never fully recovered.

Bernard Meninsky: The Red Hat (Margaret Meninsky), 1919 (oil on canvas). Collection of the Ferens Art Gallery, Hull

Fractured lives

Meninsky and his wife Margaret had a second son, Philip, in 1919 and the portrait above shows her pregnant with the child. Meninsky’s career started to climb once again: he returned to teaching, exhibited with the London Group of artists and had a one-man show at the respected Goupil Gallery in London. His exhibition was focussed around a set of mother and child drawings he had done based on his own family and was a sell-out. Then life took another dramatic turn when his wife suddenly left him; she died a year later. Meninsky seems to have had no option but to place the children with carers. Eldest son David went to stay with Meninsky’ s sister Kate in Liverpool, and baby Philip was settled with couple in Hertfordshire where he stayed until he was 18, only occasionally seeing his father.

Bernard Meninsky: Mother and Child, 1919 (oil on canvas). Collection of the Stanley & Audrey Burton Gallery, University of Leeds

Life and work continue

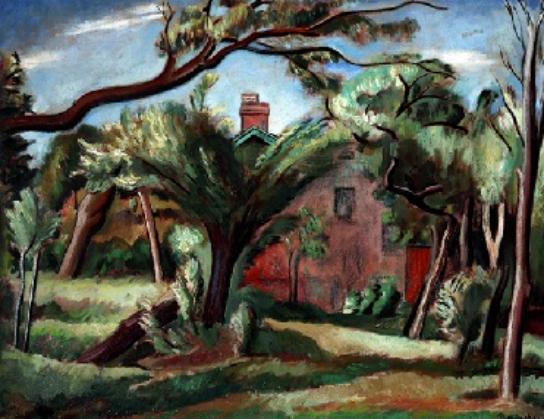

Despite Meninsky’s domestic troubles, his career progressed well during the 1920s: a book was published of his mother and child drawings, he became teacher of life drawing at Westminster School of Art and regularly featured in exhibitions including solo shows. In 1927 he married again, to Nora Barczinsky, who was of Polish-Jewish heritage, and their relationship was an enduring one. Despite the stability of his new relationship, Meninsky continued with mental health struggles and was treated for clinical depression in 1931 and 1934. Trips abroad to Spain and the South of France seemed to alleviate his darker mood. He also found solace by spending time in nature closer to home, resulting in some verdant landscape paintings.

Bernard Meninsky: Cookham Dean, Berkshire c.1930 (oil on canvas). Collection of the Victoria Gallery & Museum

World War Two and after

On the outbreak of war in 1939, London art schools closed down and Meninsky moved first to Tunbridge Wells, then Marlow in Berkshire before setting up in Oxford, where a friend arranged teaching work for him at Oxford City School of Art.

Meninsky returned to London in 1945 and returned as a tutor at the Central School of Art. In the years between 1946 – 50 he illustrated a published volume of Milton’s L’Allegro and Il Penseroso, had a painting trip to Torremolinos in Southern Spain, curated an exhibition on the art of drawing for the Arts Council and had a solo show at Zwemmer Gallery, London. To the outside world his life seemed busy and successful.

Bernard Meninsky: Still Life with Apples, c.1947 (oil on canvas). Collection of the Victoria Gallery & Museum

Meninsky’s art

While he had an original vision and sensibility, Meninsky had a range of artistic influences that show through in his work. Like so many young artists of his generation, the work of Paul Cezanne (1839 – 1906) was key, especially in his landscapes and still life where traditional perspective and compositional forms were abandoned in favour of bringing out underlying shapes and structures. This can be seen in his paintings of apples above. With his figures, critics have compared his work to the Neoclassical period of Picasso from around 1917 - 1925, revealed through a certain heaviness and monumentality in his depictions. Meninsky himself referred to the Florentine early Renaissance master Masaccio (1401 – 1428) as an important inspiration.

Bernard Meninsky, late 1940s. Cover of 1981 exhibition catalogue

An ending and a footnote

The depression that had dogged Meninsky finally became too much for him to bear, and he committed suicide in February 1950 in his London home. According to his wife Nora, he believed his work was unappreciated and that he was neglected as an artist. To a neutral observer, this seems surprising given the extent of his exhibiting record but he perhaps compared himself to contemporaries, such as Jacob Epstein and members of the London School, who had gained a higher profile in the intervening years. Nevertheless, Meninsky’s work continued to be exhibited in the following decades and his widow Nora Meninsky’s generous bequest to the Contemporary Art Society enabled the remaining works in her care to be gifted to public galleries across the country. The University of Liverpool was the fortunate recipient of seven works in 2000.

By coincidence, we were pleased to exhibit works by Meninsky’s son Philip in an exhibition called The Secret Art of Survival in 2019 – 20. Philip was one of the remarkable survivors of harsh conditions as a Far East prisoner of war in Thailand, and recorded life in the camp at the risk of his own life.

Further information:

Online:

An analysis of Meninsky’s artistic practice on Art UK by Laura Baliman

See more artworks by Bernard Meninsky on Art UK

Discussion of Bernard Meninsky by Ben Uri Gallery

Published:

Ann Compton (ed): A Singular Vision (exhibition catalogue), University of Liverpool & Contemporary Art Society, 2000

John Hoole (ed): Meninsky (exhibition catalogue), Museum of Modern Art, Oxford, 1981

Jean-Pierre Lehmans (ed): Bernard Meninsky (exhibition catalogue), Archer Gallery, London, 1972

Keywords: Bernard Meninsky, Ukraine, Liverpool, Liverpool School of Art.