Time on His Hands: Phil ‘The Clock’ Irvine

Posted on: 29 March 2025 by Phil Irvine & Kim Fisher (VG&M Visitor Services) in 2025

The clocks at the VG&M are springing forwards for British Summer Time! In this blog we chat to Phil ‘The Clock’ Irvine who looks after the clocks in our Art and Heritage collections and we take a closer look at some of our interior clocks and his career over the past 60 years.

Phil can you tell us a bit about yourself and what do you do at the VG&M?

I visit the VG&M on a weekly basis to wind the clocks on display in the first-floor galleries and outside the Leggate Theatre and I make repairs when required and I carry out any required ongoing maintenance. I have repaired the mouldings on one of the gallery long case clocks that were missing and also created a new winding key from scratch.

I have always had a natural ability for this type of work and I have taken on the restoration of items that people thought couldn’t be restored. I was given many projects by English Heritage, The Council for the Care of Churches, plus many individual parishes up and down the country. I have restored many clocks in the Merseyside area, and you have probably looked at one some time without knowing it.

Left – Phil pointing to the upper part of the clock that he restored on gallery, Right - One of the keys that Phil has made for a VG&M clock.

How did you get into this career?

I got my metalworking skills from my grandfather on my mother’s side of the family, and I used to help him as I was growing up; I still have his tools in my workshop and use them today.

At school I was kicked out of my metalworking class because I told the teacher that he was making the fire incorrectly as I had learned how to do this at my grandfather’s forge and so I was sent to woodworking classes instead.

Woodworking skills have come in very handy as can be seen in this photograph where Phil is making the pattern for the clock at Irlam Station, Manchester.

In 1962, I was apprenticed to Master Joiner and French Polisher although I had learned many skills from my father Robert who was also a Master Joiner. I learned my skills with wood working, French polishing and metal working during this time, and took on various antique restoration projects.

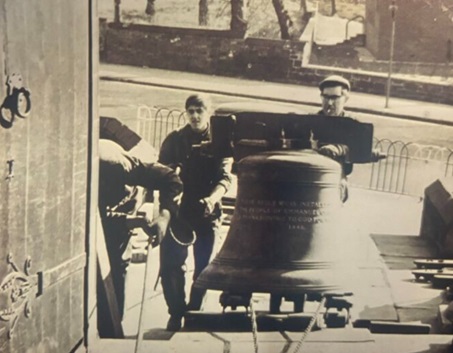

Phil (left) with his Father Robert (right) with one of the bells from Emmanuel Church that were being installed into Christ Church, Bootle.

In 1971, my local parish church asked if I could remove their defunct church bell. This led to further work for the Diocese Redundant Church project which involved removing stained glass and church fixings and fittings for restoration and to be used in other churches. I also carried out bell work, which was removing a ring of six or eight bells from a redundant church and re-installing them in another church (photograph above).

This also led to my restoring and maintaining tower clocks and smaller antique domestic clocks. At St Luke’s Church in Crosby, I overheard a conversation that the clock also needed repairing so I put myself forward for the job – this was the first clock I ever repaired and restored with no prior training.

My professional reputation grew from this restoration work, and I was invited to join the Artworkers Guild by Donald Buttress, Queens Architect for The Palace of Westminster and Westminster Abbey. This led to a lot of further work, including the maintenance of The Four Apostles (Mathew, Mark, Luke and John), the turret bells at Liverpool Metropolitan Cathedral.

VG&M Curator of Heritage and Collections Care Leonie Sedman was given Phil’s contact details by her father’s friend who was a clock collector and said that Phil was the only one for the job and that’s how he started working at the University of Liverpool.

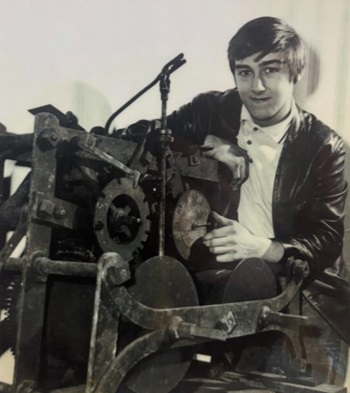

Phil in the 1960s with the clock from Liverpool Industrial School (1846).

What is the best thing about the job that you do?

The never-ending variety of work, as no two jobs are ever the same. I’ve been lucky to travel all over and go to lots of interesting places. If you love what you do, you’ve never worked a day in your life!

Do you have a favourite clock from our collection?

There is an early 18th century Samuel Townson clock on which I think the marquetry work is some of the best I have ever seen.

The case is made of walnut and rosewood and has inlaid bird and flower marquetry. The long case itself would be made by a specialist cabinet maker and not by the clock maker themselves. Samuel Townson was apprenticed in 1695 and became a Freeman of the Worshipful Company of Clockmakers; a London guild that is the oldest surviving horological institution in the world, from 1702-1738.

Left - The Samuel Townson clock on display at the VG&M in 2015, right – closer detail of bird and flower marquetry.

What can you tell us about the clocks that you look after in the VG&M?

The clocks on display in the galleries were all made in Liverpool.

If there are visitors in the galleries, they always ask questions like “How long will the clock run when fully wound” – which is usually one week and “What are the lunar dials for?” The lunar dials display phases of the moon as it waxes and wanes through its monthly cycle, the number alongside it showing the lunar date and not the calendar date.

The backplate of the Condliff clock in gallery three is inscribed with the words ‘Lunatic Asylum Ashton Street,’ the former home of University College Liverpool from 1882-1892. James Condliff was a very famous Liverpool clockmaker and became one of the most successful in the country and this clock may well have been one of the first clocks in the University’s collection when the asylum building was sold and renovated by Waterhouse.

One of the VG&M gallery clocks showing phases of the moon.

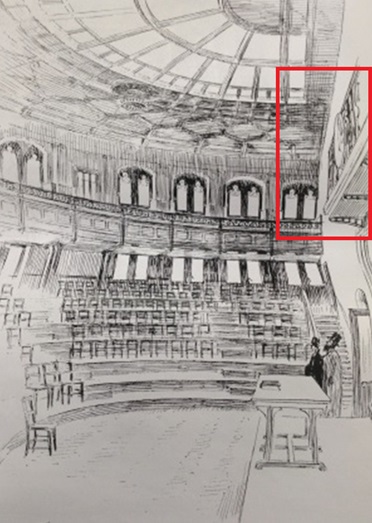

The clock on the wall outside the Leggate Theatre was presented to University College Liverpool by Charles W. Jones in 1891 and we believe it may have been one of the clocks that was originally installed in the lecture theatre itself and connected to other clocks in the building.

A sketch from around 1892 showing a large clock on the right-hand balcony which may have been the Charles W. Jones clock.

At the Jubilee Clock Tower opening ceremony on 15th November 1892 we know that a clock was positioned in the Tate Hall Library by the spiral staircase and it was connected via electricity to clocks in the tower clock, lecture theatre and grand entrance hall.

When jam manufacturer William Hartley ascended the stairs to start the motion of the tower clock, dignitaries waited in the Tate Library to see the interior clock start to move. The hands on the main tower clock dials moved as the clock drive turned and the other three clocks were connected and driven by electric impulses every minute. This arrangement was set by the clock makers and Professor Campbell Brown from Chemistry advised on the synchronisation.

The clock was later been moved and installed in the university’s engineering department and then moved back over to the VG&M prior to the 2008 opening. When Phil was installing the clock in the VG&M he noticed an inscription that mentions the switching gear that sent electrical signals to the clock tower and even today the minute finger still has the contact on it.

Phil winding the Charles W. Jones clock outside the Leggate Theatre and a close up of the contact on the minute finger.

What is the job you are most proud of?

I think the job I am most proud of is the candlesticks from Tonbridge School Chapel after a devastating fire in 1988. The bases and feet from some of the candlesticks were missing and there were no photographs to show what they had looked like originally. I used the patterns of the acanthus leaves from other parts of the design to create new feet and used these as examples of my restoration work showing the before and after photographs in a portfolio that enabled me to join the Artworkers Guild.

Left – candlestick fragments from Tonbridge School Chapel after the fire, Middle & Right – Phil’s restoration work and finished candlesticks

Now that you are retired with more time on your hands, what projects are you working on for yourself?

I now only work at two locations during the week – the VG&M and Sefton Church.

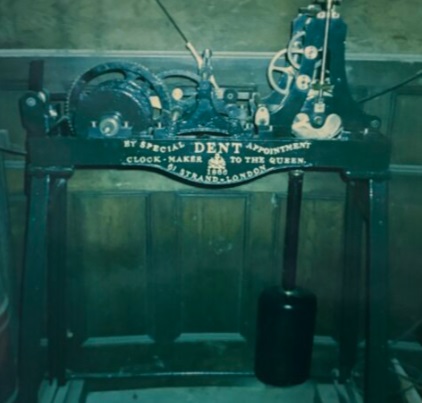

This summer I hope to install my favourite turret clock made by Dent of London into my kitchen. I have the provenance for this clock, including a lithographic print of the church it was originally installed in and I also have an original portrait engraving of E.J. Dent, the maker which will go onto the kitchen walls alongside it.

Dent’s Turret Clock that currently resides in Phil’s workshop.

Do you prefer when the clocks go forward, or when they go back?

When the clocks go forward, a clock only needs to be wound on by one hour. When the hour goes back, I need to wind the clock on by eleven hours, and I have to wait for each hour, half hour and possibly quarter-hour to chime, which (pardon the pun) is frustratingly time consuming! I prefer the Spring, when I only need to adjust clocks forward by one hour.

Keywords: Phil Irvine, Clock, Spring, British Summer Time, VGM, Horology.